Killing journalists: when law and order and justice system fail

Killing, harassing journalists

The photo exhibit at the conference shows scenes from the Maguindanao massacre site and the arrest of prime suspect Andal Ampatuan

Killing journalists: when law and order and justice system fail

PACHICO A. SEARES

October 19, 2017 ( CJJ12 )

Media shares burden of reducing risk to safety of its practitioners

SINCE Nov. 23, 2009, the Ampatuan Massacre trial has moved oh so slowly, stuck in the mire of simultaneous hearings on petitions for bail filed by 58 of the 197 accused.

Five years ago on that day, 32 journalists and media workers, along with 26 other men and women, died in the worst single political killing in the country since the Edsa Revolution of 1986.

While 197 were charged with 57 counts of murder, only 98 are detained; the rest are still at large. Petitions for bail, in which the state must present “strong evidence of guilt,” have made the process crawl, nowhere near the line when the main trial could start.

Ill-prepared

The justice system clearly wasn’t prepared for dealing with this kind of a crime: a massacre with multiple victims and accused and hundreds of witnesses.

While the state has made adjustments in handling the trial of the century, the case seems not to have moved at all, even as problems of disappearing, bought, or harassed witnesses, along with possible corruption of some prosecutors, bug the government’s case.

The Ampatuan Massacre trial graphically demonstrates the major reason impunity, which is blamed for the incidents of violence, has gone unchecked in many areas of the country. While the wailing is louder over the death of journalists, there are other victims, including activists, social workers and labor reform advocates.

Because of its epic scale, the Ampatuan Massacre trial is getting the attention, at least once a year. But how about the smaller cases of violence in which the same slow-moving justice apparatus is used?

Cebu Declaration

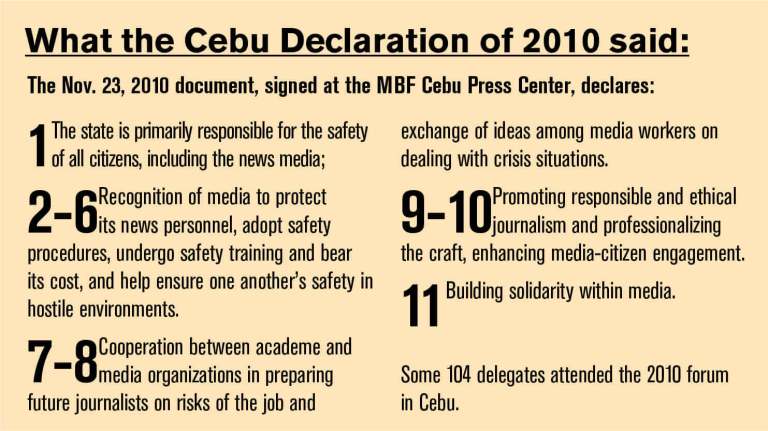

Last Nov. 23, 2010, at the MBF Cebu Press Center in Cebu City, the so-called Cebu Declaration, adopted by the First Media Conference on the Protection of Journalists, listed 11 points:

– Five on measures to heighten awareness of safety among media personnel;

– Two on sectors like the academe and journalists to “work together” in preparing present and future practitioners for situations of crisis and violence;

– Three on the usual themes of responsible journalism, professionalizing the craft, and solidarity among news organizations and journalists;

– The 11th point is No. 1 in the Cebu Declaration’s list: the state being primarily responsible for the safety of all citizens, including the news media, should immediately act “to end the culture of impunity.”

There is that word again, impunity, which means, plainly, freedom or exemption from punishment, penalty or harm. When the killer gets away with murder, that’s impunity.

And there are two ways: he is not arrested or he is arrested but is not swiftly punished. The first involves law enforcement; the second involves prosecution and trial.

The “Media under fire” conference was held on Nov. 23, 2010 at the Marcelo B. Fernan Cebu Press Center to mark the first anniversary of the Nov. 23, 2009 Maguindanao massacre. At the conference were (from left): Anastasia Isyuk of the International Committee of the Red Cross; Cherry Ann Lim of SunStar Cebu and the Cebu Citizens-Press Council; Red Batario of International News Safety Institute, Center for Community Journalism and Development and Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists; Police Chief Supt. Alex Paul Monteagudo; Ledrolen Manriquez of the Peace and Conflict Journalism Network; and Nonoy Espina of the National Union of Journalists

Justice system

In 2010, when the Cebu Declaration was adopted, enormousness and enormity of the problem of the justice system must not have been seen the way it’s being recognized now by those closely engaged with the Ampatuan Massacre trial: victims’ relatives, government and private lawyers for the prosecution, and media-watch organizations.

Otherwise, Item #1 in the declaration would’ve touched specifically on that problem of providing due process to the accused without negating the ends of justice.

The Ampatuan Massacre is an aberration, a once-or-twice-in-a-lifetime crime, though it magnifies in a colossal way, the risks that media faces and the problem of impunity.

OK, tuck it away for a while for this question: Does impunity still exist even after the Ampatuan Massacre? Apparently, it does, since the killings of journalists and others have continued and the killers are not held to account for the crime.

Where it exists

Impunity exists in areas where political warlords rule; where police, prosecutors and judges can be bought off; where the community tolerates excesses of politicians in the name of peace or progress; where the press is weak because it is inept or corrupt.

The Cebu Declaration talked of a professionalized, responsible, and ethical press, adhering to high standards of the craft and engaging with citizens on public concerns. It called for solidarity within the media.

Tall order for a community press beset with problems of finances, training and equipment along with professional and personal rivalry and I-can-part-the-sea hubris of some newsroom managers who demand servility from underpaid minions.

11 commitments or goals for media in the face of assaults

Yet the arduous task of improving the community press must be waged.

Media can demand that the state do its thing in boosting law enforcement and overhauling the justice system, even as media must do its part in reducing risks of newspapering and broadcasting.

Editors need to be resourceful and patient in answering such questions as this one from a reporter: “Please tell me how better writing can discourage a gunman from shooting me.”

(This is a reprint, re-titled and slightly revised, of the Nov. 22, 2014 Media’s Public column of Pachico A. Seares, public and standards editor of SunStar Cebu and executive director of the Cebu Citizens-Press Council.)

(CJJ12 was published in hardcopy in September 2017.)