Standing tall: surviving the ‘80s

Standing tall: surviving the ‘80s

BY LINETTE RAMOS-CANTALEJO

September 2012 (CJJ7)

“Four dead, two survive.” If there was a publication covering newspapers in the 1980s, the fall of three local dailies in a span of two years would have made headlines. So would have, along with the casualty news, the success stories of two other dailies.

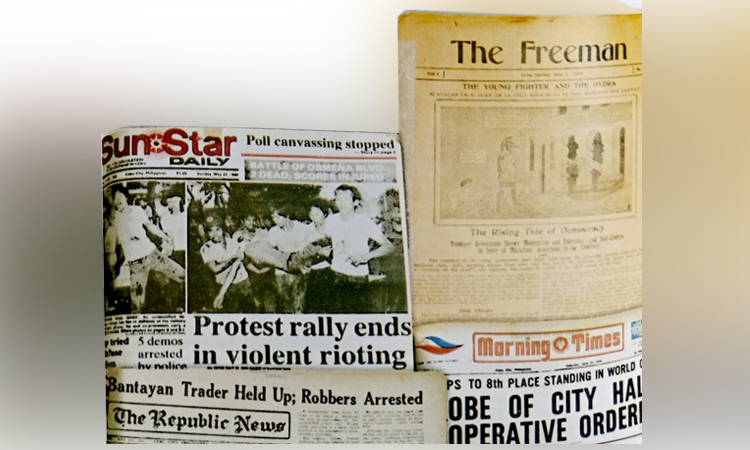

Front pages of the old Freeman before it “folded up on the eve of World War II”; Morning Times, and “the young upstart” SunStar.

Offices of The Freeman at corner D. Jakosalem and P. Gullas Sts. and SunStar along Osmena Blvd., across the street from the SSS Bldg. in Cebu City of the 1980s.

Four dead, two survive contest.

If there was a publication covering the newspapers in the 1980s, the fall of three local dailies in a span of two years would have made headlines. And so would the success stories of two other dailies.

At the start of the decade, five local dailies were in circulation-The Freeman, Visayan Herald, Republic News, Cebu Advocate and Morning Times. Barely halfway into the decade, three already folded up as the others struggled to survive amid challenging times.

Cebu Advocate was started in 1965 by Cesar A.V. Aleonar, who owned a small printing press. The started to have paper problems when Aleonar got sick in 1978 and died in 1982. Finally, in 1984, it shut down operations after the military identified one of its columnists as a dissident, said Manuel Satorre Jr. in the 1993 book “The Rise and Fall of Philippine Community Newspapers.”

Morning Times folded up in the same year for similar reasons. What started as a guerilla newspaper became successful in the 1960s under Pedro D. Calomarde as publisher. By 1971, he had 16 people operating the paper’s letterpress and linotype, with four people running the editorial department. Six years later, the paper’s struggles started when Calomarde suffered a heart attack. His second wife and children fought over control of the paper. By 1984, the paper had to close.

A year later, Republic News also shut down. Publisher Dioscoro Lazaro was on top of the operations when the owners, the Cuencos, took control of the paper in 1983. When Jesus Cuenco started sitting a publisher, trouble reportedly began, Sator said. Jesus is the brother of former Cebu

City congressman Antonio Cuenco, who was political affairs minister in the ’80s.

The veterans were eased out, “and replaced with aspiring journalists who could be dictated by the paper’s political creators,” Satorre said.

Republic News began running articles critical of the Marcos administration, sometimes bordering on libel, replacing what he said were once balanced views of the paper. As a result, advertisers got scared, so advertising and circulation dropped, forcing the owners to shut down operations in 1985.

Visayan Herald, put up by retired public school supervisor Alejandro “Al” Alinsug in 1976, eventually followed suit and closed. In “Cebu Media History: Evolving through 100 years 1905-2005,” Godofredo Roperos said it succumbed to management problems.

The stories of these once patronized dailies provide lessons for publishers and newspaper managers.

Satorre pointed out that a paper’s survival should not be left to a single individual because if that publisher or manager goes, so does the paper. Also, papers motivated by things other than journalism-those that operate to protect the political and financial interests of its backers and papers not run as a business venture are bound to fail.

“They will survive only for as long as they remain useful to the owners and are subsidized. If subsidy is withdrawn, the paper can fall. If the reading public withdraws its patronage because the paper has practically become a political organ and has lost its credibility, then it will have to fold To survive, a paper should therefore be run both as a business venture and as a vehicle to serve the information needs of the community,” Satorre noted.

But there were also success stories.

The Freeman, which was revived by former Cebu congressman Jose Gullas in 1965, became a full-fledged daily in 1969 and continues to be in circulation today under publisher Juanito Jabat. Among its first editors were lawyers Romulo Senining and Pachico Seares, who was credited for developing the mass appeal of the paper.

Despite being padlocked by the military in 1972, the Freeman survived Martial Law to become one of only two newspapers that remained in circulation at the close of the 1980s.

In “The Rise and Fall of Philippine Community Newspapers,” Dr. Crispin Maslog counts the ample financial resources of the Gullases, who also own Cebu’s largest university, the paper’s editorial prudence, and its choice of editors and reporters as among the reasons behind the Freeman’s success.

Although owned by a family of politicians, the Freeman, he said, maintained its independence.

“In a city where newspapers appeared to be split along political lines, the Freeman, under Seares, remained independent. … It has shown fairness and fair play in the presentation of news. The paper has also adhered to ethical practices in journalism,” Maslog wrote.

This independence, he added, was made possible by the publisher’s financial backing, in the form of capital and modern printing facilities, and a free hand in running the paper. Hence, the paper had no reason to give in to pressure from advertisers and politicians, allowing it to keep the readers’and advertisers’ loyalty.

In 1982, Sun.Star Cebu joined the media fray and has since managed to gain the trust of the community, owing largely to the integrity and credibility that its pool of editors and reporters strives to keep.

For Seares, who was Sun.Star Cebu editor-in-chief from 1982 to 2010, having the right people to run the paper, the amount of independence they’re given to run it, adherence to truth, fairness in reporting and sobriety in opinion-making, enterprise, courage, espousing the causes of the oppressed and prodding government on vital services, among others, contribute to the paper’s integrity and credibility and in gaining public trust.

For the Freeman and Sun.Star Cebu, it was also about timing and the environment—coming in at a time of rapid economic growth, which meant more money for advertisements, and a rising readership base that allowed the papers to grow.