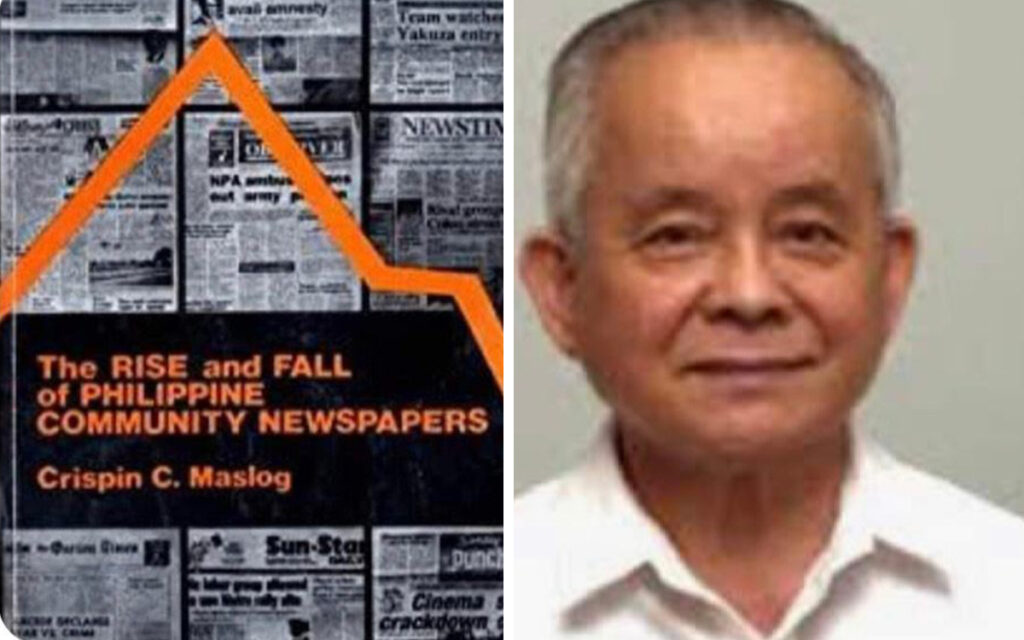

The Freeman: Cebu pioneer

The Freeman: Cebu pioneer

CRISPIN C. MASLOG

2012 (CJJ7) [Last updated in January 2023]

[From “The Rise and Fall of Philippine Community Newspapers” by Crispin C. Maslog, published in 1993 by Maslog and Philippine Press Institute, funded by Konrad Adenauer Foundation. ]

THE publisher of The Freeman, then a weekly semi-broadsheet (from 1965 until 1969 ) was not discouraged by the big threat his young publication was facing: enough advertising support. Instead of backtracking, the publisher took another step forward— putting out The Freeman as a daily, the first newspaper, in 1969, to become a full-fledged daily in Cebu City.

To the skeptics then, putting out a daily for a city of around 340,000 people (in 1969) may have seemed a big gamble. It was chancy, but the gamble paid off.

The history of The Freeman can be traced back to 1919, when the brothers Paulino and Vicente Gullas, who belonged to a prominent family of politicians in Cebu, published a trilingual newspaper called The Freeman. On the eve of World War II, the newspaper folded up.

Revival after 2 ½ decades

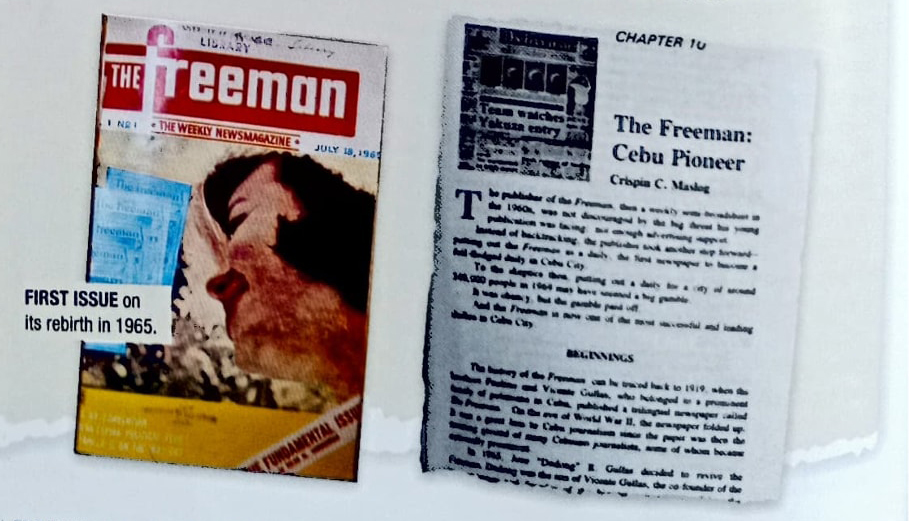

In 1965, or after about 25 years after original paper became defunct, Jose “Dodong” R. Gullas decided to revive The Freeman or, more precisely, use its name for a new publication. Dodong was the son of Vicente Gullas, co-founder of the pre-war paper and founder of the biggest university in Cebu, University of the Visayas. He also owned a printing plant, J&J’s Printers. So, it was here that The Freeman was reborn, on July 18 that year.

The Freeman was put out first as a weekly newsmagazine under the aegis of J and J’s Publications. In 1968, The Freeman’s format was changed into a semi-broadsheet, with mostly feature-styled stories.

Not until 1969 did The Freeman become a daily, coming out six days a week, from Tuesday to Sunday. Four years later, it became a daily that came out seven times a week.

Freeman editors

Atty. Romulo Senining, who later became a city court judge, was the first editor. He stayed on until 1966. Dodong Gullas took over the editorship from Senining, relinquishing it to another lawyer, Pachico A. Seares, in 1968. (Seares in the paper’s staff box was managing editor in the first three years and only the third editor-in-chief, but from Freeman’s first issue until 17 years later, he was actually the top editor and in charge of editorial operations.)

Seares served the longest (17 years), resigning only in 1982 when he was recruited by Anos Fonacier to edit the fledgling Sun.Star Daily, now the biggest circulation paper in Cebu and The Freeman’s chief competitor.

It was under Seares that The Freeman flourished. He developed the mass appeal of the paper. Circulation rose to 9,600 copies daily—the largest in the Visayas and Mindanao at that time. It meant a reach, with pass-on readership included, of some 50,000 readers.

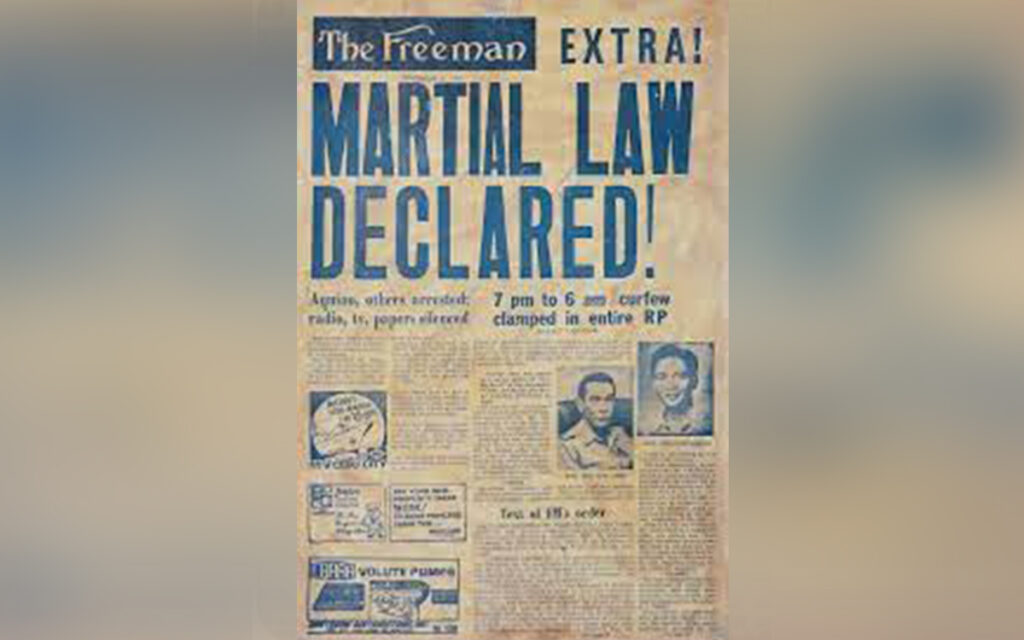

Last issue, an extra edition, of The Freeman before its closure for about a month in the early days of martial law, which was officially declared on Sept. 21, 1972.

Columnist Mojares arrested

When Martial Law was declared on Sept. 21, 1972, The Freeman and its printing plant were padlocked by the military, and one of the paper’s columnists, Resil B. Mojares, was picked up and detained for months by the military. Mojares, a nationally known literary figure and Palanca award-winning writer, had been hitting hard at the Marcos administration in his columns.

The last issue The Freeman was able to put out was an extra edition, carrying the Martial Law story. The paper remained silent for a month after that.

After Seares’ resignation in 1982, the editorship was passed on to his associate editor, veteran journalist Juanito V. Jabat. One of the things Jabat did a year later was to put out an extra edition of the Aquino assassination in 1983. It was the only paper to have done so.

Independent stance: a hallmark

The Freeman has tried its best to keep itself an independent newspaper. The Gullas family had been, for years, identified with the Marcos Administration. The publisher’s brother was, in fact, the Cebu governor during the Martial Law years. But The Freeman, according to its editors, did not allow itself to be used as a mouthpiece of the then ruling party.

There are many reasons for The Freeman’s success. One of them is timing of its entry as a daily in the city in 1969. As the city population grew in the sixties, the interest of readers and advertisers in weeklies had waned. The pace of life in the city had grown faster. And city had grown faster. And to match the pace, the city needed daily newspapers.

Under an able editor, Seares, the paper grew rapidly, increased its circulation and influence, and kept its policy of independence a working rule.

Indeed, The Freeman’s independence, a hallmark of successful community newspapers, carried the paper through thick and thin. It kept the readers’ loyalty even when times were bad.