A newspaper column, not a broadcast, set off governor’s lawsuits.

Surviving libel, other complaints

1. A newspaper column, not a broadcast, set off governor’s lawsuits

PACHICO A. SEARES

May 3, 2023

The governor won the libel case in the prosecutor’s office, the RTC and C.A. but lost in Supreme Court. How could the facts and the law be seen differently by lower court judges and SC justices? Odd but good for the journalist.

THERE were three reported complaints that Cebu Gov. Gwendolyn Garcia filed in 2007 against broadcaster Leo Lastimosa, all based on his column in The Freeman of June 29, 2007 titled “Si Doling Kawatan”:

(1) a civil case for damages before the Barili Regional Trial Court;

(2) a criminal case for libel filed before the Cebu City prosecutors office, which found probable cause and filed the information with the Regional Trial Court; and

(3) another criminal case for libel before another branch of the RTC, based on a complaint filed before the city prosecutors.

The first was dismissed in April 2008. The second was also dismissed after the governor withdrew it. In the third case, Lastimosa was convicted by the RTC, the conviction was affirmed by the Court of Appeals, which however reduced the amount of damages, but — surprise, surprise — was acquitted by the Supreme Court.

Print lent more impact to the news.

LAYERS. The surprise, if not the oddity of it, is that the first three layers of justice — the prosecutors, the RTC judge, and the panel of C.A. justices — failed to see that “Doling” in the defamatory material was not Gov. Gwendolyn. The jurists were using the same standards of determining the fourth essential element of the crime of libel, the same jurisprudence, and yet they reached contrasting conclusions. Prosecutors, RTC and C.A. said Doling was ‘Dolyn (from Gwendolyn) but the Tribunal said she was not, or more accurately, the witness — the third person who identified the governor as the defamed person — didn’t give a convincing basis for his identification. His only basis: Doling sounds similarly ‘Dolyn.

Apparently, it’s not enough for the court to rely on the word of the third person. The witness must present a good reason for identifying the “victim” of libel. The lower court judges believed the testimony of one person other than the parties in the case was enough and they must accept the identification. Not so, ruled the SC.

What that instructs the journalist is to keep on waging the legal battle even if he loses in the first three stages of the lawsuit, as Lastimosa did. That would stretch though the hassle and stress from the inconvenience and expenses. It took Lastimosa almost 16 years from the year he wrote the column and was sued until the SC acquitted him.

Lastimosa being cross-examined by the governor’s lawyer

PRINT, NOT BROADCAST. The other “peculiarity” of the case, which actually must no longer be strange to the Cebu media community, is that the governor used the newspaper column for her complaints, not the broadcasts, which are often more bitingly defamatory.

The commentator with a mic is generally less restrained and more vicious than the same commentator stringing words together on a typewriter or computer. Aside from the writer having an editor vetting his work before publication, the broadcaster is loose with his mouth, no gag when he opens it.

The choice of print over broadcast by the hurt libel “victim” striking back may impair the journalist’s defense. In Lastimosa’s case for example, his parent media organization, ABS-CBN, reportedly refused providing him a lawyer and paying his other legal expenses as he was sued for his newspaper column, not for what he said on radio or TV and, besides, the broadcast firm was not included in the lawsuit.

2. Why the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts’ ruling: ‘Doling’ was not sufficiently identified as Gwen

PACHICO A. SEARES

[First published as News+One in SunStar of April 6, 2023]

‘Third person’ witness merely based his impression that the defamed person was the governor because of similarity of the sound of the nicknames.

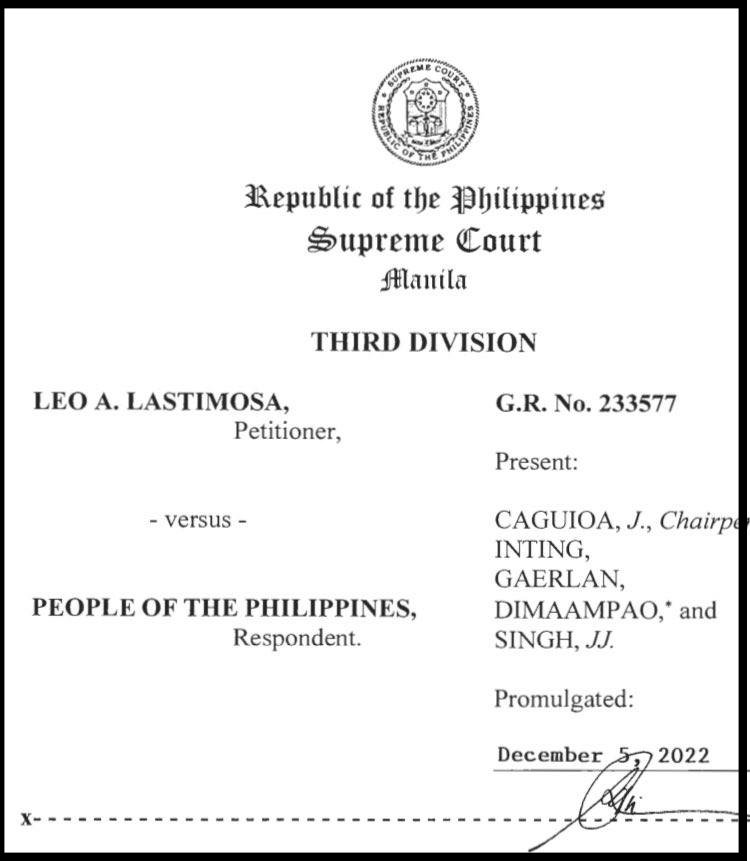

THE Supreme Court has decided that a newspaper column written by Cebu broadcaster Leo A. Lastimosa almost 16 years ago was not libelous, thus setting aside the finding of guilt by the Court of Appeals, which earlier affirmed his conviction before the Regional Trial Court.

The SC third division — in its 18-page decision promulgated December 5, 2022 but publicized only last Monday, April 3 (2023) — ruled that complainant Gov. Gwen Garcia was not identified or identifiable as “Doling” in the alleged defamatory column.

“There is reasonable doubt as to the element of identifiability, which is necessary for a libel suit to prosper,” said the ruling penned by Associate Justice Alfredo Benjamin Caguioa and concurred with by AJs Henri Jean Paul Inting and Samuel Gaerlan. The third member, AJ Japar Dimampao, was on leave.

Three of the four elements of libel were present, the SC said, but the last element — that the aggrieved person was named or identified — was missing.

Overall, proof was not “beyond reasonable doubt,” without which a criminal charge would fall.

RELATED: 1. Seares: What Judge Yrastorza used to convict Leo Lastimosa, September 6, 2013. 2. Seares: Leo Lastimosa’s defense, October 8, 2016

DEFAMATORY. First, the column titled “Si Doling Kawatan” was “indeed defamatory,” the court noting that the character Doling in the June 29, 2007 column in The Freeman was described as “abrasive, cruel, arrogant, and, worst, a thief.” There was “no doubt” about it being defamatory, the SC said.

As Journalism 101 instructs, “defamatory” and “libelous” are not synonymous. A defamatory statement must be accompanied with three other elements for the crime of libel to exist.

MALICIOUS. Second, there was malice. Malice, the court said, is presumed because of the defamatory nature of Lastimosa’s article. He wrote about a public official and jurisprudence says “criticisms against public officials or public figures are considered privileged — and thus malice is not presumed.” But that exception does not apply, the court said, when the criticism “extends to the private life of the public figure.”

Lastimosa wrote about the private life of “Doling”: her dealings with her neighbors, how she was “abrasive with them when she amassed wealth and gained political power,” her having sown fear of her in the community. Lastimosa didn’t comment about the public life of “Doling.” She was supposedly a barangay captain and no criticism about her conduct in office, the ruling said.

WAS PUBLICIZED. Third, there was publicity. The article was published in a daily newspaper, which Lastimosa admitted.

‘DOLING’ MAY NOT BE GWEN. It was in the fourth element — the identifiability of the victim — where the high court disagreed with the rulings of the Cebu RTC and the Court of Appeals.

The defendant must have published a defamatory statement concerning the plaintiff. Leo did publish the “offensive” column but was it about Governor Garcia? Was “Doling” Gwen? That was the core of the issue, which was to determine the court’s decision.

The SC found that the “Doling”-as-Gwen identity was not established by the prosecution:

[] No third person was presented, which “could’ve established beyond reasonable doubt” that “Doling” and Gwen are the same person. No witness proved that “Doling” was the governor.

[] As to the witnesses actually presented, the high court, unlike the RTC and the C.A., didn’t find prosecution witness Glenn Baricuatro’s “feeling” or “belief” about the identity of fishmonger “Doling” enough to prove that she was Governor Gwen. The SC said Baricuatro’s only basis for his “impression” was that “Doling” sounded similar to Gwendolyn, with stress on the name’s second part “dolyn.”

This journalist was summoned to testify regarding a journalism class informal survey on the identify of “Doling,” which he wrote about in a newspaper column. Not one of the students referred to was presented by the prosecution, the court said, thus the testimony was hearsay.

Besides, the SC noted that “the testimony of Atty. Seares, when read in full, was in fact detrimental to the prosecution’s case.” The students in the survey — who said they believed it was Gwen — said so only because they heard some radio commentators say that it was Gwen. The other students — who said they believed it was not Gwen — had not heard and weren’t influenced by any radio commentator.

AT STAKE IN THE SC CASE, aside from the impact on the litigants’ respective professional and personal reputations: Lastimosa was to pay Governor Garcia damages of P500,000 or half a million pesos, down from the P2 million awarded by Regional Trial Court Judge Raphael Yrastorza Sr. in his August 10, 2013 decision convicting the broadcaster. The whooping damages, on top of the small fine of P6,000.

Imprisonment or stay in jail was not in the RTC and C.A. rulings, except the subsidiary imprisonment if Lastimosa would fail to pay the P6,000 fine, which was a remote possibility. Notably relevant here is the SC standing policy that encourages judges to shun the penalty of jail term for libel unless the judge finds it necessary.

As it turned out though, Lastimosa was acquitted of the crime charged, with the SC’s ruling concluded with: “Let entry of judgment be issued immediately.”

3. What Judge Yrastorza used to convict Lastimosa

PACHICO A. SEARES

[First published in SunStar of Sept. 6, 2013]

The RTC ruling that convicted the broadcaster relied on evidence of his past attacks against the governor. The SC rejected that, saying previous acts weren’t evidence to identify the libel ‘victim’

THE stories reporting the news that Regional Trial Court Judge Raphael Yrastorza Sr. convicted broadcaster-newspaper columnist Leo Lastimosa of libel in the complaint filed by then Cebu governor Gwen Garcia didn’t cite specifics as to what the judge relied on for his Aug. 30 decision.

The next day’s papers told the basic 5Ws but little on how and why. Often, there’s no time for that in the heat of deadline and pressure of space. But the second/third-day story could’ve done it.

Stories after the event were about Yrastorza rejecting suspicion that Capitol allowances influenced his decision and the judge explaining why Leo had to stand up for one hour 45 minutes while the decision was being read (1. he didn’t want to give Leo special treatment; 2. Leo appeared fit and didn’t ask to rest).

Governor Garcia testifies at the sala of RTC Judge Raphael Yrastorza.

Took two clerks, one after the other, and one hour and 45 minutes to read RTC Judge Yrastorza’s decision. During the entire reading, Lastimosa was standing. [From FB post]

Libel elements

What in the judge’s mind convicted Leo?

Any decision on libel must deal with the four essential elements of the crime: identification, publication, malice, and defamation.

If a defense lawyer knocks off one element, his client walks. Most lawyers strike at three or four, hoping the multi-pronged assault will disable at least one.

Leo admitted publication. What he needed to refute were identification, malice, and defamation. Did he succeed? To the judge, he didn’t.

Focus on identity

The decision said Leo questioned “merely” the identity of “Doling,” the woman he wrote about in his “The Freeman” column. Leo didn’t question allegations of malice and defamation during the preliminary investigation at the prosecutor’s office and in the petition for review with Department of Justice.

If that is true, defense concentrated its attack on identity. Leo contends Gwen is not Doling who, he says, is a work of fiction. Gwen insists she is Doling and all the defamatory accusations against Doling (thievery, unexplained wealth, vengefulness) were all directed against her.

To identify Doling, Gwen herself and Glenn Baricuatro, an employee of her brother (then congressman Pablo John), testified. I was subpoenaed as witness for the prosecution but mainly to identify two columns I wrote on the issue. The judge in his decision considered me “an independent witness.”

To identify the victim of libel, only one witness other than the complainant is needed. Gwen’s testimony about her “absolute certainty” she is Doling may be self-serving as she is the complainant. Baricuatro’s testimony may also have less probative value as he was employed by Gwen’s brother.

Past acts

As to the News Sense columns about my U.P. Cebu class survey as to who is Doling, the judge said that “in the court’s mind, criteria for the survey were not clearly delineated (so) that its authenticity and credibility are doubted.”

Besides, the context of what I wrote must have been lost to the litigants and the court since only one column (July 19, 2007) was presented as people’s exhibit when there were two columns about the issue.

The second column (May 3, 2011), which I referred to in my testimony, explained that nine of 15 mass-com students identified Doling as Gwen from media reports while the remaining six didn’t recognize Gwen in Doling because they hadn’t read or heard about it.

Anyway, the judge shot down that testimony and also defense witness Democrito Barcenas’s declaration that Doling is not Gwen.

The judge could’ve relied only on Baricuatro’s testimony to identify Doling. But Glenn’s was also tainted by his links with the Garcia camp. So what must have convinced the judge that Doling is Gwen?

Conduct as evidence

A Rules of Court provision says evidence that one did a certain thing at one time cannot prove that he did the same or similar thing at another time. But the exception to that rule on “Previous Conduct as Evidence” is that evidence of past acts may be used to prove “a specific intent or knowledge, identity, plan, system, scheme, habit, custom, or usage and the like.”

The decision highlighted the word “identity.” Leo, in previous attacks (14 newspaper columns from Nov. 9, 2006 to June 2, 2007), named the governor.

He didn’t name Gwen in his Doling column but he enumerated sins similar to Doling’s in the columns in which he named Gwen.

Those previous attacks did him in. And the judge used Leo’s past columns not only for identifying Doling but also for finding malice and defamation in Leo’s Doling column of June 29, 2007.

The question is whether the past columns, for any of which Leo has not been convicted or charged, can be used to prove malice and defamation in the Doling column.

Who is Doling?

Identification is crucial because the other elements of the crime also hinge on it.

The judge identifies Doling as Gwen but the accused doesn’t agree. Appellate courts will settle that, among other issues that Leo’s lawyer may raise on appeal.

Was there failure to present each side’s case thoroughly? If there wasn’t, could the judge have seen it in a different light?

Until now there may be no absolute certainty about Doling’s identity. And that argues for the imperative of proving the journalist’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

‘Doling” was a fictitious character, claimed Lastimosa’s defense. The governor, according to that argument, is not a fish vendor or a barangay captain.

4. Lastimosa’s defenses heavily relied on identity of ‘Doling’

BY PACHICO A. SEARES

[First published in SunStar of Oct. 8, 2016]

Broadcaster’s lawyer tore down identification by ‘third-person’ witness, casting doubt on basis and reason for his belief that ‘Doling’ was the governor.

IT seemed odd that two Cebu broadcasters were sued for libel because of columns they wrote in newspapers, not for opinions they expressed on air.

Radio tends to induce more defamatory material than print. Ask any radio commentator. They feel freer and more powerful before a microphone. Libel complainants still have to learn how to gather evidence thrown in the wind, which used to be what broadcast talk was about. Print journalists, knowing the printed word is caught on paper, are mostly cautious.

DYSS commentator Bobby Nalzaro was sued by now Cebu City Mayor Tomas Osmeña for a column in Sun.Star. DYAB commentator Leo Lastimosa, by then Cebu governor Gwen Garcia for a column in The Freeman.

The Lapu-Lapu City prosecutor decided against Bobby and filed the information for libel in court. Bobby raised the ruling to Department of Justice for review. DOJ cleared him. Cebu Regional Trial Court convicted Leo who appealed the decision to Court of Appeals. C.A. affirmed the conviction.

WHY DOJ CLEARED BOBBY NALZARO. Media’s Public, Oct. 1, 2016

Whatever the basis for the complaint — print, broadcast or online — the essential elements of libel are the same.

DOJ ordered Nalzaro’s case dropped. It saw his comment as not defamatory and not malicious. There was no quarrel about publication and identification: It was Tomas he talked about and it was published.

C.A. affirmed Lastimosa’s conviction because it believed he identified and defamed Gwen and there was malice. His major defense from trial court to the C.A. Special 19th Division has been that “Doling,” the subject of the “offensive” column (“Si Doling Kawatan,” June 29, 2007, The Freeman), is not Gwen.

Was Gwen identified?

The motion for recon to C.A.’s July 27 ruling, which Leo through his lawyer Celso V. Espinosa filed Sept. 9, dwelt on (1) the issue of identification, (2) C.A’s giving more weight to Gwen’s testimony and her witnesses and exhibits and (3) the “absence of clear evidence” to prove guilt. But it’s the ID thing that appears to be the bigger bone of contention.

Is Gwen “Doling”? She was not named, she has never been a fish vendor or a barangay captain, and Doling’s description does not match Gwen’s, Leo’s appeal said. She was fiction; it was a parody of sorts. One cannot defame or slander a non-existent person; thus malice becomes irrelevant.

The C.A. ruled that it is enough “if by intrinsic reference the allusion is apparent” and by description or reference to facts, readers may know the person alluded to. All it needs is that a third person “recognized or could identify the party vilified.”

Or so the C.A. ruled. If the MR won’t persuade the C.A. to change its mind, most likely Leo will go to the Supreme Court.

The high tribunal’s decision ruling may enrich jurisprudence and cast light on some journalistic legal questions. Such as whether testimony of a a relative and political ally of the complainant and similarities in characteristics (e.g. sounds in the names “Gwendolyn” and “Doling”) constituted enough identification.

Other columns

But what may inform journalists who seek refuge behind the defense of “absence of malice” is one C.A. argument on the ID issue: Descriptions of Doling, the C.A. said, as “loud-mouthed, foul-tempered, corrupt, abusive, vindictive and cruel person” in the litigated column were also written about in Leo’s past columns that referred to or were associated with Gwen.

It’s a case where a column is judged not solely by itself but in relation to other previous columns. The RTC and C.A. apparently established identification and malice that way.

The Supreme Court though might look at it differently and use other standards on journalists who report or comment on public officials. As public persons or figures, they are not “ordinary citizens” and they deserve rigid scrutiny.

***

No ‘hunting license’ for the press

Here are parts of the C.A. decision on the Lastimosa case that may help media practitioners in their work. Please don’t cup your ears, do listen.

— “The danger of an unbridled irrational exercise of the right of free speech and press, that is, in contempt of the rights of others and in willful disregard of the cumbrous responsibilities inherent in it, is the eventual self-destruction of the right and the regression of human society into a veritable Hobbesian state of nature where life is short, nasty and brutish.”

— “The press is the servant, not the master of the citizenry, and its freedom does not carry with it an unrestricted hunting license to prey on the ordinary citizen.”

As we Google words like “cumbrous” and “Hobbesisn,” we note that the quotes are from the Supreme Court (Fermin vs. People). The C.A. obviously cited them for media’s benefit.