Honoring Plaridel father/icon of Philippine journalism

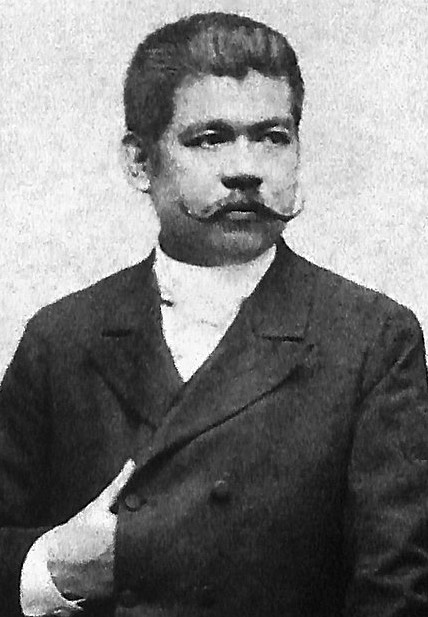

Marcelo H. del Pilar in Madrid. [Wikipedia photo]

Honoring Plaridel, father/icon of Philippine journalism

Republic Act 11699 of 2022, which declares August 30 of each year as National Press Freedom Day and a working holiday, honors Marcelo H. del Pilar as “father of Philippine Journalism.” The National Press Club recognizes del Pilar, or Plaridel (his pen name), as “icon” of Philippine journalism. 2023 is the second year of National Press Freedom Day since the law was passed and the first such celebration by the Cebu media community.

Statue in Bulacan. [Marcelo del Pilar Shrine photos]

1. Del Pilar had ‘modern sense of mass publicity,’ did a master stroke in propaganda

LEON MA. GUERRERO

[Published in “Philippines Free Press Online,”

philippinesfreepress.wordpress.com, Dec. 13, 1952]

Plaridel’s was a different kind of heroism. Del Pilar — born Aug. 30, 1850; died July 4, 1896 — “starved for an ideal, to be lonely among many enemies, to suffer indifference and ignorance, to die a beggar and lie buried in a borrowed grave.”

OF all our national heroes, Marcelo H. del Pilar was, perhaps, nearest to the modern Filipino. Modern in his concept of political activity, modern in his belief in organization, modern in his skillful and efficient use of propaganda, he was the prototype of the modern politician, lawyer, newspaperman and civic leader. Del Pilar should surely be ranked on equal terms with Rizal, Bonifacio and Aguinaldo as a leader of the victorious revolution against Spain.

Few Filipinos realize that the Spaniards, who were after all the best judges of their enemies, placed Del Pilar ahead of Rizal and the others. General Ramon Blanco, governor-general of the Philippines at the outbreak of the Revolution, said that Del Pilar was “the most intelligent [of the Filipino politicians], the true soul of the independence movement, very superior to Rizal.”

We do not have to take the judgment of the Spanish Governor-General. Our own historians uphold the proposition that Del Pilar inspired the organization of the Katipunan, if he did not actually found and direct it. Proof of this are the facts that the by-laws of the Katipunan were submitted for approval by Bonifacio to Del Pilar, that Bonifacio used the letter of Del Pilar sanctioning the organization to recruit adherents, and that the Kalayaan, official organ of the Katipunan, carried the name of the absent Del Pilar as editor. Thus was explicit and formal recognition given to the man whose ideas and ideals inspired the revolutionary movement. So intimately was Del Pilar connected with the Katipunan, and so highly was he regarded by its leaders, that Bonifacio reverently copied the letters of Del Pilar to his brother-in-law, Deodato Arellano, considering them as sacred relics and, together with the letters that he himself received, as guides for action.

Surname was added

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar was born on the 30th of August 1850. It is a pity that our people did not see fit to celebrate the centenary of his birth two years ago, but the opportunity has passed forever. His birthplace was the sitio of Cupang in the barrio of San Nicolas, municipality of Bulacan.

The real surname of the family was Hilario. Del Pilar was added only in obedience to the famous decree of Claveria in 1849, the same that added Rizal to the name of the Mercados. It is probable that noble blood ran in Del Pilar’s veins. His mother was a Gatmaytan, and the prefix Gat indicated her descent from the ancient Tagalog aristocracy.

From the beginning he came in conflict with the friars, who were to become his lifelong enemies. He was a fourth-year law student at the University of Santo Tomas when he quarreled with the parish priest of San Miguel, Manila, over some baptismal fees. He seems to have been so deeply affected by this incident that he interrupted his studies for eight years, during which he worked as a government clerk. When he was finally admitted to the bar, he was already 30 years old and married to his cousin, Marciana Hilario del Pilar.

“A government of friars”

To understand his subsequent career, it is necessary to realize the political situation at the time. The real and effective political power in the Philippines during the close of the Spanish regime was exercised by the religious orders. We had what Del Pilar termed “La Frailocracia” in one of his most renowned works, that is to say, a government by friars.

They had attained this position through a shrewd and masterful strategy. To the Filipinos they denounced the abuses of the civil government, and proclaimed themselves the only protectors of the common people. To the civil government, in turn, they accused the Filipinos of being anti-Spanish and proclaimed themselves the most effective defenders of the Spanish sovereignty.

Thus, playing one against the other, the friars were able to maintain their predominance over both, in much the same way that certain elements in our own time proclaim themselves the only ones who can get American assistance for the common people, and brand their political opponents as anti-American and anti-democratic (the present equivalent of the terms mason, filibustero, and libre-pensador, so useful to the friars.)

Counter-strategy

Such a strategy of duplicity and deceit could not then, as it cannot now, succeed forever. In the end it was exposed and defeated, as it will again be discredited and repudiated in our own time. But it still worked when Del Pilar, as a young lawyer, returned to his native province and immediately proceeded to oppose it.

His counter-strategy was simple, but it reveals his political talent. He allied himself in every possible way with the Spanish civilian officials, who did not relish any more than he did the soberanía monacal, the monkish regime. Most of us, looking back at the past through the pages of a textbook, have grown to believe that all the Spaniards were bad, that their government was uniformly oppressive, that they knew nothing of constitutions, democratic rights and modern political institutions.

The fact is that Spain itself had undergone a long and ferocious revolution and civil war, and that the Spanish people had proved with their blood their understanding, devotion and right to constitutional government. There were Spanish liberals as well as Spanish reactionaries; the issue in the Philippines, as Del Pilar and Rizal saw it, was whether the liberals or the reactionaries, as represented by the friars and their supporters, would gain the upper hand in the distant colony, and whether or not the Spanish constitution and its bill of rights, and the Spanish system of representative government through the Cortes, would be extended to the Filipinos.

“Throw the friars out!”

One may appreciate this in a flash from the title of one of Del Pilar’s pamphlets, which was called simply: “Viva España! Viva el Rey! Viva el Ejercito! Fuera los Frailes!” That is to say, “Long live Spain! Long live the King! Long live the Army! Throw the friars out!”

Such was Del Pilar’s political slogan, and he put it into practice by winning to his side liberal Spanish laymen, Filipino local officials, and the officers of the guardia civil. His father had been three times gobernadorcillo of Bulacan, and Del Pilar was used to the ways of provincial politics. He maneuvered to have one of his relatives, Manuel Crisostomo, named gobernadorcillo of Malolos, and, when the latter was relieved on suspicion of subversive activities, to have another relative, Vicente Gatmaytan, appointed in his place. Del Pilar also seems to have exercised great influence on the Spanish governor of the province, Manuel Gomez Florio.

With this organization behind him, Del Pilar took the side of the cabezas de barangay of Malolos in a bitter dispute with the parish priest over the collection of excessive taxes. Subsequently, in another controversy over the control of the civilian authorities in public funerals, he even convinced the Spanish governor to order the arrest of the friar-curate. In 1887 and 1888 he expanded his field of activities and prepared eloquent denunciations and memorials directed to the Governor-General and to the Queen Regent herself.

Pamphlets in Tagalog

Obviously, the daring provincial politician could not for long escape the vengeance of the religious orders. At their instigation, a confidential investigation was held. Del Pilar was accused of being “anti-Spanish”—familiar phrase—and the counsel of subversive elements against the friars. The case was taken to Malacañan itself. This time, even his friend, the Spanish governor of Bulacan, was unable to protect him. On the 28th of October 1888, Del Pilar hurriedly took a ship to Spain as the decree for his exile from his native province was about to be signed.

In the Spanish metropolis, he plunged once more into political activity. He intrigued with the principal Spanish politicians, trying to secure promises and concessions. But above all he embarked on the gigantic one-man propaganda campaign which was to become his lifework and his main contribution to the Revolution. He edited La Solidaridad almost single-handedly, but with such rare ability that Rizal contented himself with occasional contributions from abroad.

Unlike Rizal, furthermore, Del Pilar had a modern sense of mass publicity. While the poet-hero wrote his tremendous novels in Spanish, a language that few Filipinos could read, Del Pilar flooded his native country with smuggled pamphlets written in simple Tagalog, a Tagalog that is still a model of lucidity, directness and force.

Ribald, coarse

Del Pilar was no academician or theorist; he was ribald, sometimes coarse, even blasphemous. He wrote parodies of the Our Father, the Hail Mary, the Apostles’ Creed, the catechism—all ridiculing his enemy the friar—and as a masterstroke of propaganda, he printed them in the same size and the same format as the pious catechism and novenas distributed by the friars to the faithful in the provinces.

It was modern propaganda; ruthless, unscrupulous, popular and tremendously effective. Yet Del Pilar was, also, a generous enemy. When his hated antagonist in polemics, the simple friar Rodriguez died, Del Pilar paid a heartfelt tribute to his sincerity, charity, love of truth, and honor, pointing out that the good father had received an exceedingly mystical education and was not to blame if he stubbornly idealized the facts of life.

When he learned from his wife that enemies, probably agents of the friars, had burned their house in Bulacan, he wrote to her: “I am not surprised over the burning of our house. Our enemies are capable of worse misdeeds! If the criminal hired for the job is one of our people, I know he was misled by his ignorance of my sincere love for him, for I cannot believe he would otherwise have sunk so low to do me harm. There is not a bit of resentment in my heart.”

One peso from his daughter

How painful it was for this man to live separated from his wife and children! It was not only the penury which he suffered in Madrid; it was most of all the absence of his loved ones that drove him to distraction. His letters to his family reveal all the goodness of that heart, hidden under the truculent and combative visage of the propagandist.

His heart bled when his youngest daughter Anita, hearing that her father needed money in Spain, sent him one peso, which she had hoarded out of the Christmas gifts given to her. Upon receiving the touching present, Del Pilar wrote to his wife: “I can’t seem to forget the peso Anita sent me. I wish you had contrived somehow not to send it so that you could have bought her a pair of shoes instead. My heart bleeds every time I think of the hard life you and our children lead, and so I am very eager to return home to be able to take care of you and our children.”

Why did he not go back? He was not living in Madrid in the style of those of our contemporaries who have access to the favors of the Central Bank. He had no dollars for nightclubs and gifts. Indeed, as he said in one of his letters to his wife: “For my meals I have to approach friends for loans, day after day. To be able to smoke, I have gone to the extreme of picking up cigarette butts in the streets.…” But his friends in Spain, as well as the family council in his native land, urged him to stay, and conscious of his duties to his people, he himself knew he had to stay.

Heroes are also human

Besides, and this is a revealing episode in his life, he did not want to bring disaster upon his family and native town. It was not without bitterness that he saw the entire population of Calamba dispossessed in the furore over Rizal’s return. He wrote to his wife: “Regarding your advice about not following the example of Rizal.. it is indeed very unfortunate! That man not only does not build, but also wrecks what others have built inch by inch by dint of hard labor. Of course, he really does not mean it, but because of his headlong ways, he brings misery to others. If my misfortunes bring blessing to others, I really would not mind them; but if they bring misery and disaster to many, then they are useless indeed!”

It is difficult to believe that these are words of Del Pilar on Rizal. But heroes are also human; they disagree among themselves. Rizal had his own reasons for returning, just as Del Pilar had his own for remaining in Spain. They had, one might say, two different concepts of sacrifice: Both were prepared to make a supreme sacrifice; Rizal was ready to die; Del Pilar was willing to face what was, to him, worse than death: exile.

But in the end, Del Pilar himself was convinced that it was useless to remain in Spain any longer. The time for practical politics had passed. Concessions would no longer be sufficient. He had learned enough from Bonifacio’s messages to know that the hour had struck for armed revolution.

Buried in friend’s crypt

Racked with tuberculosis, his constitution broken by years of hardships and hunger, penniless in a foreign land, Del Pilar dragged himself to Barcelona to wait for a ship back home. He was so wretchedly sick that, like an animal, he had to climb on hands and knees up to the poor garret where he lived.

He grew so much worse that he had to suspend his trip. He was taken to a charity ward. There, on the 4th of July 1896, a few days before the Cry of Balintawak, a few months before the execution of Rizal, and half a century exactly to the day before the proclamation of our independent Republic, Del Pilar died, a pauper, almost deserted, far from his beloved family, consoled only by the last sacraments of his old enemy the Church. There was not even enough money to pay for a grave. His body was buried in the private crypt of the family of a friend, on a hill overlooking the sea that lay between him and home.

Different concepts of service

Thus died the greatest of the Bulakeños, and one of the greatest of the Filipinos.

How many of us know even now where the remains of Del Pilar are buried?

With characteristic indifference, we let his body rot in a borrowed grave in Barcelona until a passing traveler took initiative, many years later, to bring back the poor bones and ashes. Today he rests in the mausoleum of the Veterans of the Revolution in Manila. He does not even have a grave to call his own. Perhaps he would rather rest there, in a common grave with those who fought for his ideals. Del Pilar was always a believer in unity, cooperation, brotherhood. That was, after all, the name he chose for the newspaper which was his lifework: La Solidaridad.

His kind of heroism

There are many kinds of heroism. There is the heroism of the martyrs like Rizal, pure and spotless victims offered in atonement for the sins of mankind. There is the heroism of the fighters like Bonifacio, bold and gallant in the vanguard of the struggle.

And there is also the heroism of those who, like Del Pilar, work and make their sacrifices in the sustained devotion of their daily tasks. Theirs is not the spectacular glory of the battlefield or the tragic splendor of the scaffold. But it is nonetheless heroic to starve for an ideal, to be lonely among many enemies, to suffer indifference and ignorance, to die a beggar and lie buried in a borrowed grave. Such was the heroism of Del Pilar.

LMG on cover of a biography of him.

Leon Ma. Guerrero was a lawyer-journalist (1915-1982) anddiplomat born in Manila. He wrote for the prewar PhilippinesFree Press (1935-1940) . He was asst. solicitor of the Departmentof Justice; a memorable experience there: he prosecuted Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in the killing of Nalundasan. After the war he became a partner of Claro M. Recto’s law office and later joined the diplomatic service. He served as ambassador to London, Madrid, New Delhi, Mexico City, and Belgrade. He wrote essays, a biography of Jose Rizal, translations of Rizal’s novels, and ApolinarioMabini’s memoirs.

2. Journalists as heroes: Plaridel’s legacy

JOEL P. SALUD

[First published by Philstar.com, printed in The Freeman of Aug. 29, 2004, submitted by Salud to the journalists’ association Samahang Plaridel during the celebration of Marcelo del Pilar’s 154th birth anniversary]

He was one of the foremost champions of Filipino nationalistic thought and freedom of expression during the dark days of the Spanish colonials.

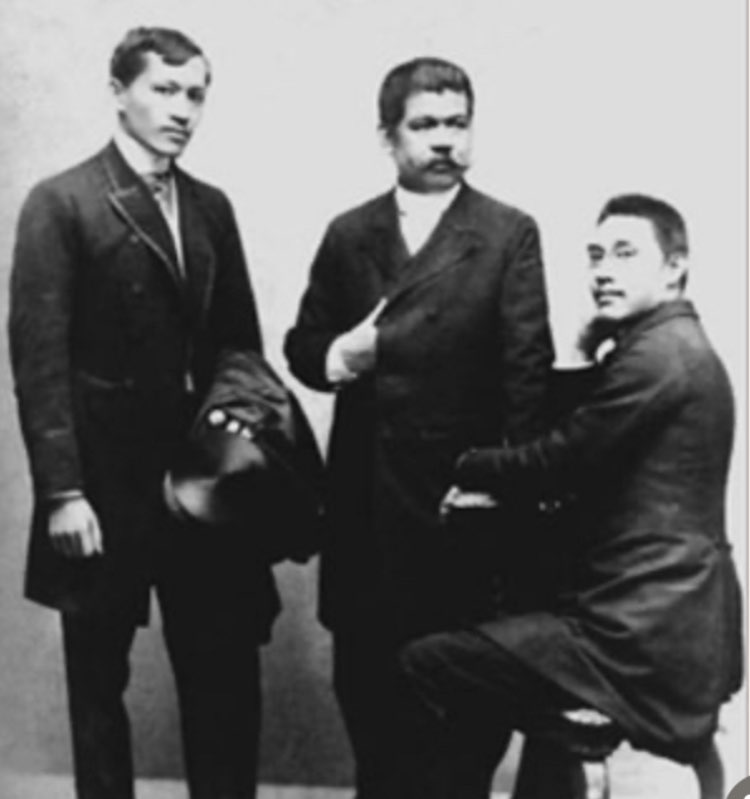

Del Pilar (center) with Jose Rizal (left) and another Filipino in Madrid.

The history of the Philippines and its revolutions is a colorful and telling tale of personal sacrifice, political and philosophical differences, chaos and cockbrained pride, courage and final glory. For if in other countries the image of a warrior with a sword or soldier and his gun has, at each instance, inspired wars, in the Philippines, the pen has constantly been the filibustero’s weapon of choice against the country’s enemies – foreign and domestic.

From the protest literature of Jose F. Lacaba, Ramon Vicente Sunico, Cirilo F. Bautista, Alfred Yuson, et al. during the martial law years up to the first EDSA revolution, to the tradition of nationalist and satirical writings of seasoned journalists and opinion writers such as Max Soliven, the late Louie Beltran, and of course, the late senator and former Manila Times correspondent Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., et al., there’s only one inspirational seed from which all these have originated: the Propaganda Movement of 1880 as led by writer-editor Marcelo H. del Pilar.

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaytan was a native of Bulacan and raised in Colegio de San Jose whom he knew the Filipino priest and martyr Padre Burgos. He was a young prodigy who lived with a Filipino priest Father Mariano Sevilla, during the first outbreak of Spanish persecution and hostilities in 1872 against indio clergymen. Father Sevilla was one of those exiled in the Marianas Islands in the aftermath.

Little was known about Del Pilar’s life during this period save for the fact he graduated with a law degree at the University of Santo Tomas. He came into the glare of history when he started a group of Filipino student nationalists that launched the first Tagalog-Spanish bilingual newspaper in the Philippines, the Diaryong Tagalog. This newspaper, funded for the most part by relatives of Del Pilar and some of his associates, was the very first of its kind, owned and run by Filipinos and carried reformist and nationalist ideas during the Spanish colonial times.

The rise of journalist-heroes

The Diaryong Tagalog wasn’t the first publication where young Filipino nationalists had bled their quills. The year 1872 to 1882 was the period we could call the “First Quarter Storm” of Filipino student activism during the Spanish colonial times.

The so-called ilustrados, or educated ones, young Filipino students belonging to fairly affluent families who were able to study abroad, particularly Spain, started engaging in writing activities and book projects to promote reformist ideas in Madrid, though subtly at first. The likes of Pedro Paterno, Gregorio Sancianco, Graciano Lopez Jaena were among the budding writers who first delved into polemics and literary bantering in a number or publications, through the hard works of Jose Rizal and Juan Atayde, the bi-weekly newspaper Revista del Criculo Hispano-Filipino was born some 10 years after the execution of the three priests Gomburza.

These publications paved the way for other periodicals to hit the newsstands. A year later, a Spanish-owned newspaper called Los Dos Mundos became the venue for articles written by Graciano Lopez Jaena, Pedro Azcarraga and Tomas del Rosario. the articles that appeared in these publications were not the “hard-hitting” articles one would expect from supposedly radical student activists. Assimilation into the Spanish Cortes and equality between Spaniards and Filipinos were the first issues they tackled, which is sort of a cloak-and-dagger forerunner to then desire for full independence. But the seed of Filipino nationalist thought were already beginning to take root around this time within the Filipino student communities in Europe. Most articles were in defense of the supposedly uneducated indio, whom the friars often tagged as indolent, apathetic and lazy.

The more radical essays of Rizal and Lopez Jaena were initially published in the Spanish republican newspaper El Progreso. The journals El Liberal, Diario de Manila El Globo, El Globo, El Emparcial and La Publicidad among others were also used as mediums for Filipino protest writings. It was during the creation of the newspaper España En Filipinas, the publication of the Filipino community in Madrid, that reformist ideas were accepted as the norm and essence of Filipino protest writing. It ran at centerstage in just a short span of time but would later die due to the disunited nature of leadership among the young ilustrados in Madrid. Around the same time, Jose Rizal was busy putting the finishing touches on his first novel Noli Me Tangere which was thereafter published in Berlin, Germany. The novel was to eventually form a more literary yet nationalistic approached to defend the indio and expose the abuses of the Spanish friars.

Del Pilar’s La Solidaridad

But it was the newspaper established by Marcelo Del Pilar (editor-in-chief), Jose Rizal, Graciano Lopez Jaena, Mariano Ponce and Pablo Rianzares in Barcelona that took the bull by the horns and became the arena of battle for reform and independence — the La Solidaridad. Its mission was “to combat all reaction, to impede all retrogression, to applaud and accept every liberal idea, to defend all progress; in a word; one more propagandist of all ideals of democracy, aspiring to make democracy prevail in all the peoples both of the Peninsula and of the overseas provinces. . .”

The obvious potential La Solidaridad displayed spurred young nationalists to join the polemical bandwagon, the more active of which were Damaso and Mariano Ponce, Jose Ma. Panganiban, T. H. Pardo de Tavera, Eduardo Casal, Isabelo de los Reyes, and even the Austrian professor and La Solidaridad supporter Ferdinand Blumentritt.

Del Pilar, writing under his nom de plume “Plaridel,” was one of the foremost champions of Filipino nationalistic thought and freedom of expression during the dark days of the Spanish colonials. He worked as editor and opinion writer, and even translator of some of Rizal’s works into Tagalog. He was also the official delegate in Spain of the Comite de Propaganda of Manila, a committee created by the ilustrados to initially campaign and lobby in Madrid for the country’s inclusion in the Spanish Cortes (Congress). It was a polemical strategy Del Pilar used to slowly introduce the idea if autonomy and final independence of the Philippines to the Spanish government.

As was expected by Del Pilar, the La Solidaridad proved to be an effective medium for propaganda, which in years that passed had strongly influenced Spanish politicians in Madrid and Barcelona and deferred for a time the persecution of indios by the friars in Manilda. The first issue of La Solidaridad were received by Filipino communities in Europe enthusiastically. According to historian John N. Schumacher, SJ in his book The Propaganda Movement 1880-1885. “Four hundred copies were sent to the Philippines, a hundred more to Basa, with the request to send to Manila those he did not need. Soon Serrano was asking for 1,500 copies, despite the difficulties of getting the paper into the country. . .” After the first few issues, the La Solidaridad moved in full swing.

Independence through propaganda

The quest for reform and assimilation into the Spanish government, which was the first stage towards full autonomy and independence of the Philippines, was clear in the mind of Del Pilar and his compatriots Mariano Ponce and Jose Rizal from the beginning.

Plaridel was a great believer in the “destiny reserved by Providence for our race. . .” At the outset, he made every effort through his writings to convince Spain of the need for proper education for the natives, the learning of Spanish, for genuine assimilation in the Spanish Congress, the privilege of natives to become part of the clergy and freedom of expression, among others, if progress and peace in the Archipelago were to be achieved. He did not risk cutting corners; his research and arguments were almost always flawless. His pamphlets and articles for the natives on the other hand were largely written in flowing, eloquent Tagalog, which he wanted to become the national language if ever the country would be granted full independence by the Spaniards one day. Having been a law student, he was, for the most part, an avid learner of Spanish politics and a critic of Spanish lifestyle and social practices, which he found altogether repulsive.

At the height of the Propaganda Movement, Plaridel launched La Solidaridad in Madrid. He functioned as sole editor and moving spirit of the newspaper in the city. At this point, financial support was increasing and so were the influx of protest articles by nationalist writers Jose Rizal, Ferdinand Blumentritt, Antonio Luna, Dominardo Gomez and Mariano Ponce. With all that money coming in, Plaridel lived a hand-to-mouth existence nonetheless.

Two battlefields

With Rizal wanting to come back to the Philippines, Spain was faced with confronting the struggle for independence from two fronts: Madrid and Manila — the bastions of ilustrado intellectual might. The strategy was something neither Spain nor the friars anticipated. Though hundreds of miles apart, Del Pilar and Rizal had always fixed their sights on the same end — independence for the Philippines. The effort in journalism and literature had shored up the work of reform and independence in the Propaganda Movement’s darkest hour. Both chose the path less taken Rizal took the avenue of heroic sacrifice. Rizal was from head to foot a man possessed and conscious of his mission to the very end, even to the point, as some historians say, of rejecting a plan of Andres Bonifacio to save him from inevitable execution. After having returned to the Philippines, he was immediately exiled in Dapitan only to face the firing squad in Bagumbayan, Manila in the name of freedom.

Del Pilar, on the other hand, took the strenuous road to convincing Spain of the jegitimacy of treating Filipinos as equals. When Rizal was banished to Dapitan, it was Del Pilar’s writings that cut a broad swathe across the friars’ thickening persecution of indios in the Philippines. Plaridel, in due course, died a very poor man in a foreign country, turning his back on riches in exchange for the hope of independence, and because of love for country.

Both journalists died as heroes, never seeing where the Philippines is today.

(This article on Marcelo H. del Pilar was submitted to Samahang Plaridel, the Journalists’ association, by writer Joel P. Salud in celebration of Del Pilar’s 154th birth anniversary.)

3. Del Pilar, icon of Philippine journalism: Rizal learned words ‘kalayaan’ and ‘malaya’ from Diariong Tagalog that Plaridel edited.

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB OF THE PHILIPPINES

[First published Oct. 17, 2016 in nationalpressclubphilippines.com]

Del Pilar edited the Tagalog section of the bilingual newspaper Diariong Tagalog. He used simple Tagalog in his articles to reach a wider audience. He could’ve used Spanish, the other language of the paper, but preferred the native tongue.

While still a young man, Marcelo H. del Pilar already knew how to plant the seeds of nationalism, and to rise and stand up against the abuses of the colonial rulers. Mariano Ponce, narrated that as a high school student in 1880, del Pilar frequently met with a group of students in Trozo, Tondo –the birth place of Andres Bonifacio and where Philippine Masonry and the Katipunan were conceived by their organizers.

In 1882, Del Pilar was a member of the group that founded the first bilingual newspaper- Tagalog and Spanish- in the Philippines, Diariong Tagalog. Though the publisher was ostensibly Francisco Calvo Munoz, a peninsular treasury official in the Philippines, the real moving spirit behind the paper were Del Pilar, who acted as editor of the Tagalog section, and Basilio Teodoro Moran, the business manager.

The newspaper was funded by several traders from Malolos, Bulacan, from where Del Pilar had formed around him a group of relatives and associates who shared his nationalistic interests.

Relative liberty of the press

The regime of Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera had seen a considerable realization of freedom of the press, and the Diariong Tagalog took full advantage of this relative liberty to speak out in favor of various reforms, as well as to promote a moderate gospel of nationalism. One of the notable articles that saw print was the “El Amor Patrio” of Rizal, translated into eloquent Tagalog by Del Pilar titled “Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa”.

A letter of Jose Rizal dated October 12, 1886, revealed to his older brother Paciano Rizal that he cannot translate the word “Freiheit” and “Liberty” in Filipino language. Rizal admitted that he only knew the words “kalayaan” and malaya” through Diariong Tagalog.

Del Pilar gave birth to the spiritual, political and nationalistic sense of the word “kalayaan”. The dictionary made by Tomas Pinpin dated 1610; Buenaventura in 1613, and Noceda in 1860 did not mention the word “kalayaan or malaya”.

Plaridel’s meaning of ‘kalayaan’

It was said that Padre Mariano Sevilla used the word “kalayaan” in his prayer booklet which means “kalangitan” or heavens – a condition of a soul that can pass through any prison without any hindrance. Prosperity was also embedded in the word “kalayaan” for those persons who had attained glory. (Veneracion: 2012).

But Del Pilar gave the emphatic meaning of the word “kalayaan” in political and nationalistic sense. Proof of this, the revolutionary newspaper of Katipunan adopted the name “kalayaan” from the article also of Marcelo H. del Pilar with the same title where he profoundly explained the meaning and the essence of the word for the freedom of his country.

Of all the forerunners of the revolution, Del Pilar was the one who inspired most Andres Bonifacio. So intimately was Del Pilar connected with the Katipunan, and so highly was he regarded by its leaders, that Bonifacio reverently copied the letters of Del Pilar to his brother-in-law, Deodato Arellano, considering them as sacred relics and, together with the letters that he himself received, as guides for action. “(Zaide, 1956)

Political program of La Solidaridad

He even moved the second president of Katipunan, Roman Basa to support the secret propagation of La Solidaridad, and Apolinario Mabini reported that Andres Bonifacio the third president of Katipunan, collected some funds to support the political program of La Solidaridad.

Majority of the famous patriots supported the leadership of Del Pilar not only in the propaganda but also in the establishment and management of Philippine Masonry, all for the liberty of the ountry through the power of the press.

Del Pilar was meanwhile occupied with other literary activities on two different fronts. From the end of 1887 he began to write political articles that he sent to his friend and disciple, Mariano Ponce, then a university student in Barcelona.

Attack on friars’ power

In articles, published in republican newspapers there, he attacked the political power of the friars in the Philippines, argued against the system of deportation by administrative decree, and presented an eloquent defense of Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere against the critique of Father Font, using the pseudonyms Piping Dilat and Plaridel.

While waging a fight in Spain against the friars and in favor of political rights, he was working on another level in the Philippines for the same ends. To counteract the influence of Father Rodriquez’s pamphlets, he wrote, under the pseudonym Dolores Manapat, a Tagalog pamphlet entitled Caiingat Cayo, parodying the title of Father Rodriguez.

In it he defended Rizal, and attacked the friars as traffickers in religion, adulterating the religion of Jesus, etc. Other pamphlets and broadsides were circulated in Malolos and in Manila in this time, and Del Pilar and his associates were responsible for their circulation, if not their actual publication.

Del Pilar in Barcelona

In the information given by the parish priest of Malolos, Father Felipe Garcia, when the expediente was being prepared for Del Pilar’s deportation in October 188, Father Garcia mentioned the manuscript copies of an article entitled “Dudas,” being circulated in the province.

This is undoubtedly was Rizal’s article España en Filipinas.

He also mentioned the pamphlet Viva España, Viva el Rey, Viva el Ejercito fuera los Frailes!, which was a collection of the various expositions presented to Centeno and Terrero before and just after the manifestation on March 1, 1888.

Propaganda organ

The arrival of Marcelo H. del Pilar in Barcelona on January 1, 1889, gave organization and the much-needed leadership to the propaganda campaign. Relatively older than the rest (he

was 38 years old at that time), already a professional and adept at propaganda, he was empowered to act as the delegate of the Junta de Propaganda, the Philippine arm of the campaign.

In Spain, while Graciano Lopez Jaena was nominally the editor and founder of La Solidaridad, Del Pilar increasingly became the driving force behind the paper as he worked energetically in setting up the paper. He gradually took over more and more of running the paper. When he finally decided to go to Madrid, the paper went with him. It could not go on without him.

Once in Madrid, Del Pilar would gather around him all the organized Filipino groups in Spain, and proceeded to expand the movement in the Philippines as well. During the early months of La Solidaridad, other activities had been going on in Madrid and in Barcelona, and Plaridel being the moving spirit of the Filipino campaign worked for an all-out, massive propaganda works.

In the name of reforms

As it turned out, La Solidaridad proved to be an effective propaganda organ both for influencing Spanish politicians and for combating the prestige of the friars in the Philippines so much to Del Pilar’s liking that he gave more and more of his time to the paper.

A study in Spain reported that del Pilar and Wenceslao Retana went to the Spanish Congress to distribute their respective newspapers to the lawmakers. La Solidaridad and La Politica de España en Filipina ultimately became a forum of debate in which their respective contributors challenged one another through their scathing and daring editorials.

Direction from Madrid

They openly exhibited their opposing views regarding the proper way of governing the Philippines from the points of view of both the colonist and the colonized. La Politica was a staunch defender of mainland interest, racial superiority and particularly was imbued with the feeling and sense of everything Spanish.

The eventual independence, or at least full autonomy, was the goal Del Pilar had in mind along with Ponce, Rizal and other propagandists.

The program of La Solidaridad and the complex organization surrounding it was professedly assimilationist, but it seems clear that the assimilationist program was much more a strategy or a first step than the ultimate goal. (Schumacher, 2005)

Solidaridad interpreted aspirations

The love and respect that everyone professed for Rizal, Marcelo del Pilar and all the other patriots who collaborated with them in the great work of national regeneration manifested clearly and openly in the political aspirations of the Filipinos.

That the La Solidaridad had faithfully interpreted those aspirations was likewise shown by the fact that its expenses were met by Filipinos residing in the islands, who there thus risking their personal safety and interest.

This will prove that Marcelo H. del Pilar was not only a reformist-propagandist as he was branded in Philippine Historiography.

‘Soul of separatism’

He was regarded by Governor General Ramon Blanco as “el Alma del Separatismo en Filipinas” The true soul of separatism in the Philippines far more dangerous than Rizal.

According to his fellow patriot and propagandist Mariano Ponce, “… Tireless propagandist in the political struggle, formidable in his attack, expert in his defenses, accurate in the strokes of his pen, unyielding in his arguments, whose knowledge and formidable intelligence commanded the respect even of his enemies, whom he had defeated more than once in contests of the mind”.

And the revealing pronouncement of Marcelo H. del Pilar to his brother in law and the first president of the Katipunan before the known founding of the Katipunan dated March 31,

1891:

Abolition of Spain’s flag

In the Filipino Colony there should be no division, nor is there: one are the sentiments which move us, one the ideals we pursue; the abolition in the Philippines of every obstacle to our liberties, and in due time and by the proper method, the abolition of the flag of Spain as well (“la abolicion en Filipinas de toda traba a nuestras libertades, y a su tiempu y conveniente razon la del pabellon de Espana tambien (Marcelo-Ka dato. Ep. Pilar, 1:246).)

This is not a declaration of pure-blooded reformist it came from the nationalistic bosom of Marcelo H. del Pilar to abolish the flag of Spain means complete independence and self-government. The Philippine Insurgent Records reported that another pamphlet of Del Pilar was distributed in different plazas in Manila titled “Ministerio dela Republica Filipina”.

Long before Bonifacio and Aguinaldo proclaimed the Philippine Republic it was already the political idea and part of propaganda of Plaridel.

‘Justice wasn’t done’

It is also noteworthy to mention the recent study of The Journal of Communication SEECI (Spanish Society for the Study of Communication Iberoamericana) founded in March 1997 by a group of teachers of Journalism and Communication Studies at the University of Madrid (Spain) in 2000 by Enrique Rios, had an article that read in part:

Although Marcelo H. del Pilar has a mausoleum in Manila as one of its leaders, we believe that justice was not done with him, because he had one of the most enlightened minds, and undoubtedly was the main brain that pointed the way to the revolution after its death, and in their contacts with Deodato Arellano, was the inspiration for the Katipunan. We ask for the rehabilitation (rectification in the proper place of del Pilar in the country’s pantheon of heroes).

Although they are not Filipinos, but by understanding the significant role played by Del Pilar, his tireless efforts in propaganda, organizing secret societies and defending press freedom, SEECI was asking since 2000 a rehabilitation and justice for “Plaridel” in the Philippine national pantheon. How much more we, Filipinos and this country are the very reason of Marcelo H. del Pilar’s lamentations and sacrifices.

Celebrate in principles, actions

From the account of del Pilar himself, Filipinos can realize and be reminded as well that his death is worthy to be commemorated and celebrated as the National Press Freedom Day not only in words but more so in principles and actions.

I believe it unnecessary for me to remind you of the circumstances that compelled me to abandon the Philippines since October 31, 1888. I was not moved by a desire to increase my personal wealth, for I had there all the element for advancement, my clientele, my interest, etc. neither was I moved by the fear of being exiled, although there I have no worse fate for the father of a family than to place a distance of three thousand leagues between him and his loved ones.

I came here for the purpose of rendering a more effective service to our unfortunate country. I came here to try by all peaceful means within the law to obtain needed reforms for my country, to look for solution that might, directly or indirectly, guarantee in the Philippines the rights of the people already guaranteed in the rest of Spain, thus raising the standard of our living and making our people ready for future progress.

Great was the task before me. Without wealth, without other help than the sanctity of our cause and my faith in the future, I saw before me as you well know, all the forces of reaction arrayed against us. Patriotism and friends gave me their support, and this support made the enterprise less onerous and my decision to fight more firm.

All means of propaganda

The campaign was started. Press, rostrum, public and private circles, primaries, meetings at Masonic Temples, personal relations, political and personal friends, in short, all means of propaganda to further the needed reforms in the Philippines, have been utilized to create an atmosphere to keep our ideals alive. Some with their donations, others with their pen, some with their speech, others with their personal influences, all with a disinterested enthusiasm, Filipinos, Peninsular Spaniards and foreigners, have contributed to strengthen our patriotic enterprise to redeem a disenfranchised people.

It is unnecessary to mention here the results of this united endeavor. The frantic attempts of our enemies to obstruct the campaign are sufficient evidence that our efforts are successful. After failing with their threats, after failing with their cajolery, they descended from their Olympian heights and decided to measure their powerful force with our feeble strength.

Newspapers and writers

They started newspapers and hired good writers, with no knowledge of the justice of our demands. When you consider the scant means at our disposal, we could not have obtained the small victories we have won and the splendid triumphs gained except from our implicit faith in the sanctity of our cause and the inner moral urge from knowing we were right. – M.H. Del Pilar, August 1892, Madrid

Plans were prepared in Madrid and the organization in the Philippines cooperated in their execution. During the three or four years that the correspondence lasted, the communion, the understanding and the harmony between the thinking brains and the obedient limbs were so perfect that, in spite of the distance that separated them, they seemed to belong to a single physical body.

What the letters did

The letters from Del Pilar and the other directive elements in Spain were awaited in the Philippines with the same anxiety and their instructions followed with the same spirit of discipline as an army listens to and carries out the orders of its general in command. And, vice versa, the letters from the Philippines lifted the hearts and filled with enthusiasm the breasts of those who worked in Spain. (Kalaw, 1956)

Without the direction of Del Pilar in Madrid, the Philippine propaganda could never have done what it did.

Unto the last breath of La Solidaridad, Del Pilar did not forsake his duties to the newspaper as editor-writer, commentator, management and publisher for seven years fighting for press freedom as well as the freedom of the country. His influence did not cease in La Solidaridad, his writings continued its influence in the Katipunan organ “Kalayaan” his patriotic examples and his revolutionary spirit moved the leaders of the Katipunan.

Bed #11

And unto his death at the Hospital de la Santa Cruz of Barcelona ward, bed no. 11 he said, “Tell my family I could no longer engage anything with them, I will die in the hand of my loyal friends. Go on and continue the campaign for the redemption and freedom of our country.”

Del Pilar passed away at 1:15 a.m., July 4, 1896.

On August 30, 1850, – birth date of Marcelo H. del Pilar – Andres Bonifacio attacked the Spanish garrison “El Polvorin” for the freedom of our country.