The early Cebu press: Cebuano literary history is intimately connected with the rise of local journalism

Retro

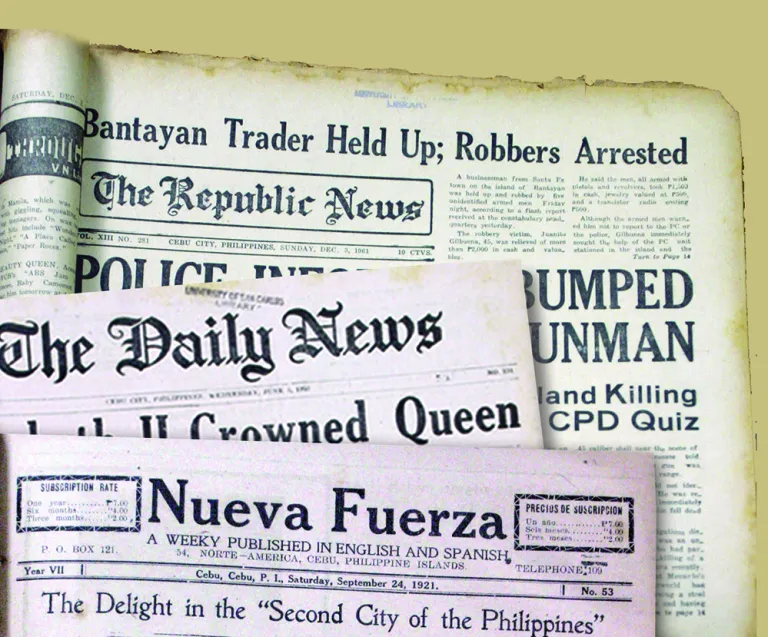

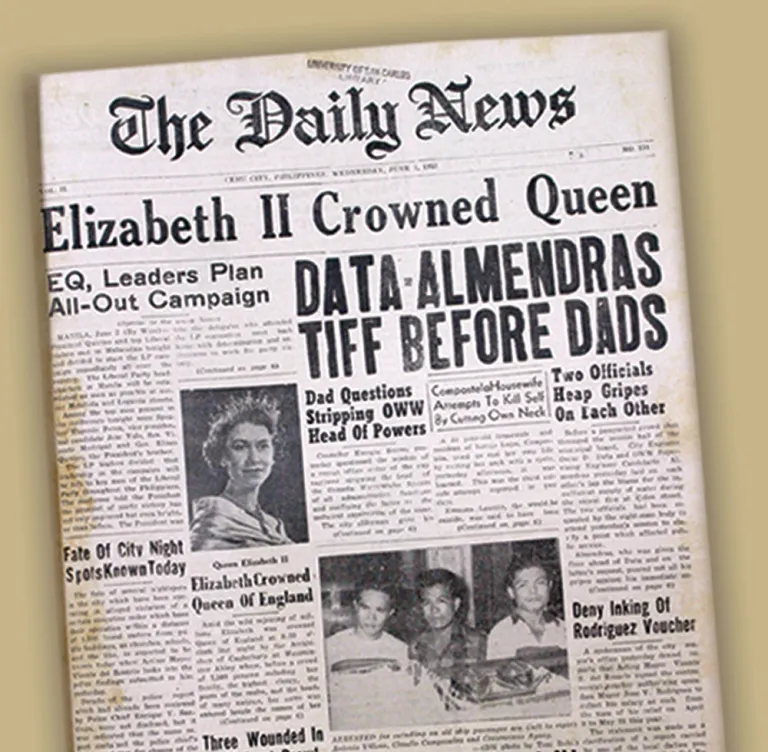

Old Cebu neswpapers. They started local journalism. Not one paper, however survived.(Excerpted from “Cebuano Literature,” San Carlos Publications, 1975)

The early Cebu press: Cebuano literary history is intimately connected with the rise of local journalism

RESIL B. MOJARES

Sept. 23, 2004

It is in the pages of local tabloids and magazines that the great bulk of Cebuano printed literature is to be found. For this reason, Cebuano literary history is intimately connected with the rise of local journalism.

CEBUANO journalism began towards the close of the 19th century. Though Cebu is the oldest Spanish settlement in the country, it was not until 1886—seventy-five years after Del Superior Govierno came out in Manila—that the first Cebu newspaper was established. The early transfer of the seat of government to Manila relegated Cebu to the realm of the provincial. Since then Manila has been the center in the centrifugal dissemination of, among others, western technology in communications.

The situation on the national scale, or in Manila for that matter, in the years prior to 1898 was not, of course, advanced. Prior to 1898, mass media were a virtual Spanish and monastic monopoly and it was a monopoly that had the following adverse aspects: the censorship of liberal expression, the discouragement of vernacular publishing, and a reportorial range that did not go too far beyond the boundaries of the capital. The native press had a very peripheral existence. Censorship, contradictory state policies on language, the disorderly state of the dialects themselves, and the dominance of monastic interests combined to hold back, even in the Tagalog provinces, the development of native and vernacular writing and publishing…

It was in this year, 1886, that the first newspaper was established in Cebu by Eduardo Jimenez Frades… This was the weekly El Boletin de Cebu, which folded up in 1898…

No other periodical is noted by W. E. Retana in the period 1886-1899 but mention has been made in other sources of two church papers in this period. One is the Boletin Eclesiastico, founded by Bishop Martin Alcocer (1887-1903), the last of the Spanish bishops in Cebu. The official organ of the diocese, its first number appeared on January 14, 1893. It ceased publication in March 1898. The Recollect chronicler Francisco Sadaba also makes a reference to a Boletin de la Diocesis de Cebu, a paper which also published Spanish verse and must have been in existence in the period 1888-1892…

The closing years of the 19th century and the turn towards the present saw the growth of Cebuano journalism. It was, on the main, composed of irregular periodicals, short-lived papers with small circulations and often wayward toward editorial and management policies, but it opened the gates to much writing and publishing and was, despite the aesthetic hazards endemic in harried popular publishing, a spur to the rise of Cebuano vernacular literature.

The early papers brimmed with a great deal of enthusiasm, “a bad imitation of Spanish journalistic style, which is quite too often simple bombast,” but this excess of zeal is in the character of rapidly changing times. Ultimately, one has to recognize that the native papers contributed a lot to the shaping of racial pride and national awakening.

Not much is known about El Boletin de Cebu which, from accounts, was the only commercial newspaper in Cebu up to 1899.The Boletin was, like all Spanish periodicals of the time, devoted to the promotion of Spanish colonial aims in the islands, in consonance with the censorship law of 1857 which barred the propagation of principles and doctrines contrary to the rights of the Spanish throne, or to the religion of the State. Its pages, though, carried the early Spanish writings of native Cebuanos, among them Mariano Alba Cuenco and Sergio Osmeña.

Still, one surmises that El Boletin de Cebu was a limited forum for native writing. If censorship was a damper for political dissent, it was also so for literary expression. Furthermore, the Spanish-language papers were limited in reach for, even towards the close of the 19th century, only from five to ten percent of the Christianized population of the islands could speak Spanish adequately.

The first Filipino papers

The influx of liberal ideas in the closing years of the 19th century and the armed as well as political campaign for independence inspired Filipino literature and journalism. Even censorship during the early years of the American occupation did not dampen the enthusiasm of the writers of the period.

In 1899, La Justicia—“the first Filipino newspaper published in Cebu”—was founded by Matias de Arrieta and Vicente Sotto, an unorthodox and volatile Cebuano, who was to make a name for himself as a writer and politician. It was a Spanish weekly born at a time of strain, for the American censors were already at work and the native insurrection was alive in the mountains of Cebu. Furthermore, the paper was allowed to be printed at the Vincentians’ Imprenta de S. Carlos only with the prior arrangement that it should not attack the Church, for Sotto was already known for his anti-Romanist views. La Justicia did not last long; the American military authorities suspended the publication almost immediately after its founding for views subversive of the American regime.

A week after it was suspended, Sotto published the equally short-lived Spanish weekly, El Nacional (1899). Sotto was imprisoned at the Fort San Pedro in Cebu for two months and six days—hence his pseudonym, Taga-Kotta—on the charge of being an agent for the revolutionary committees of Manila and Hongkong. But his journalistic career did not end here. In 1900, the plucky Cebuano writer founded El Pueblo, also a Spanish-language paper, and was several times prosecuted for libel and sedition. All told, there were reportedly fifty-four cases for libel and sedition brought against him.

With a prison sentence hanging over his head for an abduction case brought against him by his political enemies, he fled to Hongkong in 1907.There he founded the bilingual fortnightly The Philippine Republic (1911), which continued his campaign against American rule. By virtue of an agreement with Governor-General Harrison, he was able to return to the Philippines in 1915. In 1919, in Manila, he founded and edited The Independent, a weekly which bolstered his prominence in the national capital. In 1931, when he was already involved in the labor movement, he established a weekly, Union, as voice of the Philippine Civic Union which sought to use workers’ action in pressing for immediate independence.

For his yeoman work in the field of Cebuano journalism and for his notable contributions to Cebuano creative writing, Vicente Sotto is rightfully called the “Father of Cebuano Letters.”

Sotto brothers Vicente — right, the younger but taller sibling —and Filemon. Vicente died in 1950 at 73; Filemon, in 1966 at 93. (Photo from the 1992 book “Vicente Sotto: The Maverick Senator” by Resil B Mojares)

Another Sotto, Filemon Sotto, is credited with having established in 1899 the Spanish biweekly, El Imparcial. A journalist and statesman, Filemon Sotto is better known in publishing as the founder of one of the most important of Cebuano periodicals, La Revolucion (1910-1941).

Side by side with the Sotto publications, the most famous of the early papers in Cebu was Sergio Osmeña’s El Nuevo Dia, which came out with its maiden issue on April 16, 1900 and was co-edited by Rafael Palma and Jaime C. de Veyra. It was the first daily newspaper in Cebu. A four-page Spanish-language paper, sold at five, then ten, centavos a copy, with a variable circulation that sometimes reached 2000, it folded up in 1903.

The first decade of the 20th century saw an ‘epidemic’ of periodicals, fed by the fever of Revolution and Nationalism. With the growing consolidation of American rule there was also the spread of liberalism. These factors, together, encouraged publishing in the provinces. Political organs appeared, local bosses set up their own presses and papers, and the church continued with the production of religious propaganda.

In 1901, Vicente Sotto founded Ang Suga, “the first Cebuano newspaper in the vernacular.” A triweekly, sold at five centavos a copy, it carried a Spanish section and, as early as 1907, started printing English reports. In the history of Cebuano literature, Ang Suga is important, for it was in its pages that many Cebuano writers first saw regular print, among them Vicente Ranudo, Uldarico Alviola, Juan Villagonzalo, Tomas Bagyo, Escolastico Morre, and others. It is also credited with having promoted a standard orthography for Cebuano and was, of the early papers, the most involved in literary matters.

The following year, 1902, two papers were founded. One was Filemon Sotto’s Ang Kaluwasan, which was later superseded by La Revolucion. The other was Ang Camatuoran, managed by the PP. Paules and the Hermanas de la Caridad of Cebu as semiofficial organ of the Church.

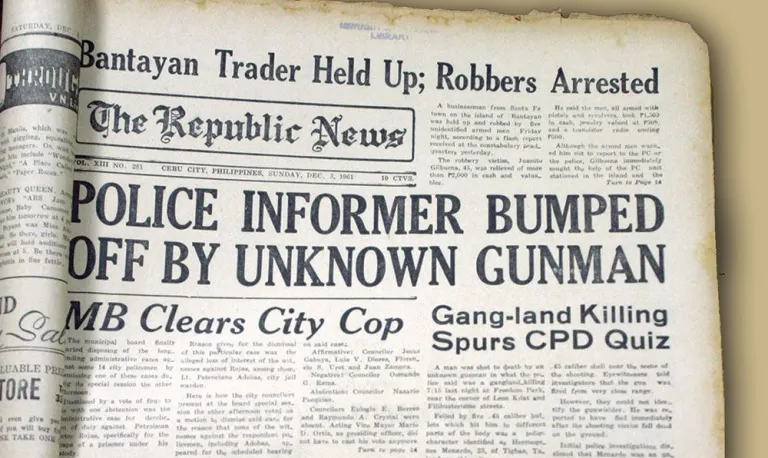

The first decade saw a spate of other papers, among them El Pais (1903), La Opinion (1904), Tingog sa Lungsod (1904), Ang Bandilla (1906), Kauswagan (1907), and El Precursor (1907). El Pais was a Spanish triweekly founded and edited by Joaquin Pellicena y Lopez. The most important of this group of papers is El Precursor (Ang Magu-una), which lasted until the eve of World War II. A bilingual paper founded by Mariano Alba Cuenco, it was the forerunner of the English daily established in 1947… The Republic News.

Publishing in Cebuano was not limited either to the city or the province of Cebu. Several Cebu towns had their own papers. Argao published La Voz de Argao (1906) and La Solidaridad Cebuana (1907). The town of Barili had Batan-ong Dila and Atong Catungod, both founded in 1909…

The first decades

The period 1910-1940 constituted a high watermark in vernacular publishing in Cebu. The surge of literature and journalism in Cebuano can be explained by a number of factors. It was a time of rising expectations: independence, nationalism, increasing commercial activity, the rise of the middle class, comparatively liberal policies, popular education. The time was permeated by the spirit of national self-exploration and experiment. After the long hibernation of the Spanish years, there was the surge, often erratic, of native confidence.

These factors created a hunger for reading materials, a need often frustrated by the lack of printed literature in the vernacular. Such a demand encouraged the furious activity of writers and journalists, many of whom were also men of public affairs, like the Sottos, the Cuencos, the Ramas, Buenaventura Rodriguez, Nicolas Rafols, and others. They played an important role in promoting, directly or indirectly, a passion for the refinement and popularization of Cebuano language and literature.

It was a time hospitable to such activity for, apart from the political and economic reasons cited, it was an interim period when Spanish was withering away and English had not as yet effectively set in as the lingua franca of the educated class. Furthermore, the use of the vernacular was aided by the infusion of egalitarian ideals which recognized the importance of the popular audience. This last-mentioned reason also had its degenerate aspect, for also characteristic of the period was that as the years wore on and opposition to American rule gradually subsided, a spirit of accommodation pervaded local writing. The politics of the press degenerated into factional and personal conflicts as the local leaders adjusted themselves to the party system introduced by the Americans. In literature, there was a turning away from the social and political polemics of Vicente Sotto towards the escapist, sentimental and moralistic strain of the vignettes and lyric verse.

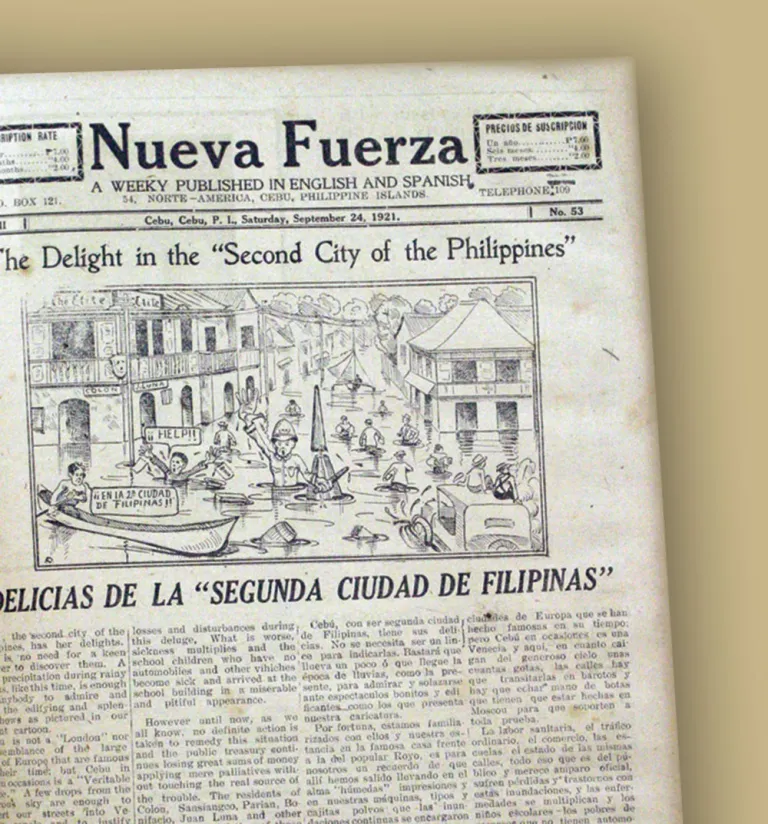

In the period 1910-1920, at least four important publications were founded: La Revolucion (1910-1941), El Boletin Catolico (1915-1930), Nueva Fuerza (1915-1940), El Espectador (1919-1922), and The Freeman (1919+). La Revolucion, a four-page trilingual daily, was founded by Filemon Sotto and had a distinguished line of editors: Buenaventura Rodriguez, Amado Osorio, Isidro Abad, Antonio M. Abad, Vicente Padriga, and others. El Boletin Catolico, a small trilingual weekly devoted to the promotion of the Catholic faith, was founded by writer-churchman Jose Ma. Cuenco. It was superseded in 1930 by Ang Atong Kabilin and by Lungsoranon in 1934. The Nueva Fuerza of Vicente Rama had a rich, checkered career: founded in 1915, it lasted until 1923, when it was absorbed by its sister publication Bag-ong Kusog, founded in 1921. El Espectador was a Spanish-Cebuano daily founded by Manuel C. Briones. The Freeman of Paulino Gullas folded up together with other periodicals on the eve of the Pacific War; it was revived in 1965 and continues today as an English daily.

All these papers regularly published fiction and verse in their pages. With these outlets, there was much literary activity. In the August 8, 1914 issue of La Revolucion, editor Amando Osorio reported, in an item entitled “100 ka balak Hingtuk-an kami,” that he had on his desk a hundred poems by a hundred different writers. Osorio exclaimed, not without a trace of irony: “Pagkadaghan’g ‘poeta’ dinhi sa Sugbo (Cebu has many poets).”

Other periodicals of this decade included Ang Pilipinhon (1911), La Nacion (1912), Los Nacionalistas (1913), La Tribuna (1913), El Anunciador (1914), El Eco de Bisayas (1915), La Opinion (1915), El Democrata (1919) and Ang Iwag (1919). Of these papers, Nicolas Rafols’ Ang Pilipinhon and the DMHM Publications’ Ang Iwag, both of which were purely Cebuano weeklies, were printed in Manila.

Most of the publications of this period are bilingual or trilingual editions. There is the trend towards the increasing use of English as the American-instituted public school system began to be effective in its aim of inculcating English as the popular medium of communication.

The language medium

What is perhaps the first purely English-language paper published in Cebu is The Cebu Chronicle, a daily tabloid founded by J. R. Flynn Anderson in 1909. This paper later turned trilingual. Preceding it was The Cebu Courier, an English-Spanish weekly edited by Jeremy Nealon. Launched on June 29, 1907, it stopped publication in August 1909.

Even before 1908 student publications in Cebu made use of English as a medium. Among these are The School World of the Cebu High School, edited by Carmen Rallos and Vicente Cuico, and The Outlook, a small periodical put out by the students of Argao.

In the succeeding decades, English gradually became the dominant medium of the press. The diffusion and eventual ascendancy of English is seen in the fact that the English section gradually became a regular feature of such Spanish and vernacular papers as Ang Suga, La Revolucion, El Boletin Catolico, El Democrata, and others. It is also seen in the growth of predominantly English papers like The Freeman (1919), The Cebu Advertiser (1922), The Guardian (1926), and Progress (1928).

The rise of English did not rise unopposed. Articles in vernacular magazines like Bag-ong Kusog and the formation of Visayan ‘academies’ attest to the fact that there were many writers who felt that the Cebuano langugage should be promoted and that the use of English, while not without benefit, would mean a diminution of identity for Filipinos. In an article published in 1918, Cebuano dramatist Buenaventura Rodriguez presented a ‘defense’ of the vernaculars, arguing that the use of a native language was crucial for the cultivation of nationality.

Spanish, which was not, to begin with a popular language, gradually lost its viability as a medium for journalism and literature. As early as 1903, it was already claimed that 11 percent of the pupils in the schools of the islands were estimated to understand English as against 11.8 percent who understood Spanish. By the 1920s, the replacement of Spanish by English as a second language was virtually complete. This language shift is shown in the Census Statistics for language and education in Cebu for 1918 and 1939.

This shift is reflected in the language medium of the Cebuano periodicals of the period. The vernacular continued to be vigorous during the pre-war years but it also gradually withered away as the medium of the local publications. There was a consequent decline in the quantity and quality of vernacular writing.

The Commonwealth years

The most popular paper established in the period 1920-1929 was The Cebu Advertiser (Ang Tigmantala), founded by Jose Avila in 1922. This paper superseded The Cebu Chronicle and, like the tabloids of the time, it also published stories and poems.

Other papers of the decade were La Epoca (1922), Ang Sulo (1924), Abyan sa Lungsod (1924), Juan de la Cruz (1929), and Sidlakan (1930)…

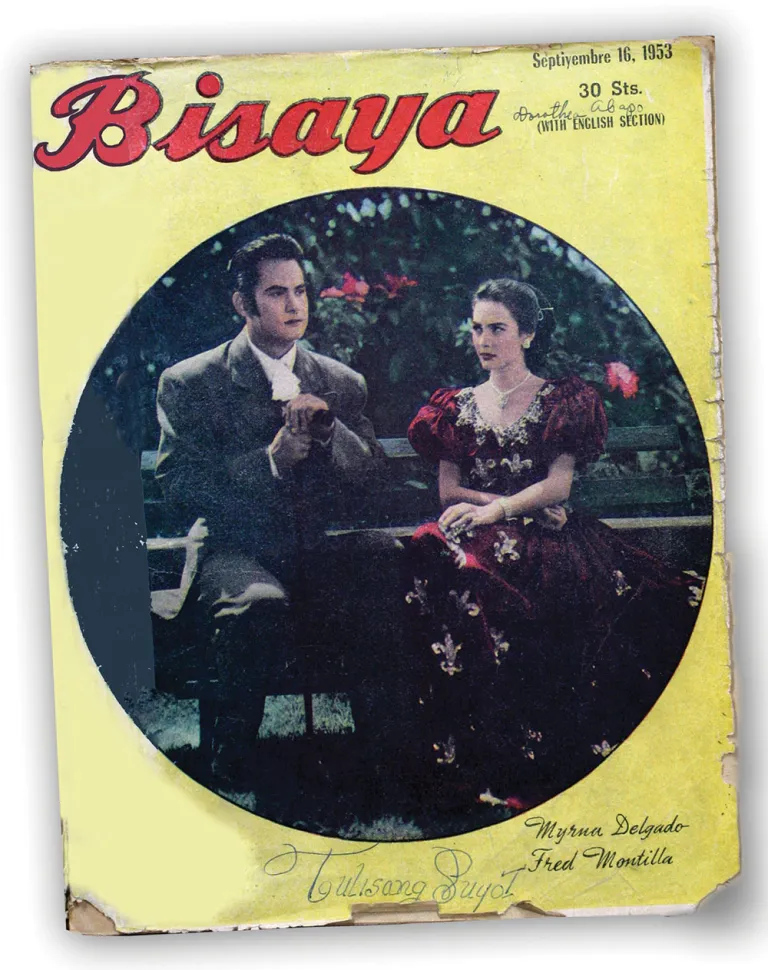

In 1930, Bisaya was founded in Manila by Ramon Roces upon the instigation of the Cebuano poet Vicente Padriga, who acted as the magazine’s first editor. Bisaya is the oldest vernacular magazine still on the scene and one of the most phenomenally successful publishing ventures in the vernacular.

Another notable publication established in 1930 was Pedro Lopez’ Nasud, a weekly magazine that did a lot to promote vernacular creative writing. It folded up, like most of the pre-war papers, on the eve of the Japanese occupation.

There was a proliferation of periodicals in the years before the outbreak of the war. In the period 1931-1941, at least thirty papers were founded, most of them short-lived. Of these papers, only one survived the war.

The most noteworthy of these publications are Babaye (1930-40), Lungsoranon (1934+), and Tabunon (1938-1941). These papers had a markedly literary character as they were either published or edited by well-known local writers, like P. Diosdado Camomot, Natalio B. Bacalso, Napoleon Dejoras and others.

Though it is true that the majority of the local papers were irregular in appearance, published either to serve personal or factional interests or for the advertisers’ money, one cannot ignore their cumulative value in fostering popular interest in Cebuano writing. Many Cebuano creative writers served on these papers. In addition, several vernacular periodicals—Tabunon, Nasud, Bag-ong Kusog, Lungsoranon, The Freeman, Lamdag, and others—offered prizes for the best literary pieces published in their pages.

The pre-war papers were varied in their format. The standard periodicals—like Ang Suga and Bag-ong Kusog—carried informal news reports, advertisements, moralistic articles, gossipy reviews of social and cultural events, ‘brief notices’ and miscellanea, fiction and poetry. In Ang Suga, for instance, the sugilagming (narrative sketch) and pinadalagan (informal pieces in prose or verse) were regular features. Popular journalism may not be a congenial setting for art but the fact that space was regularly given to literary pieces and that the editors themselves were often creative writers of note aided in the fostering of literature…

That popular magazines represent the lowest common denominator of literary taste is true to a large extent. But credit must be given to the many periodicals which, sometimes quixotically, actively sought to foster the acceptance and improve the quality of Cebuano writing. Lungsoranon and Silaw, for instance, ran regular columns on the writing of verse, authored by poets P. Diosdado Camomot and S. Alvarez Villarino, respectively. Lamdag had a regular page, “Uban sa mga magtatampo (In the company of contributors),” written by fictionist Flaviano Boquecosa, which discussed problems in writing. Literary criticism, as in the examples cited, was not sustained nor was it of a uniformly purposive quality but it remains nevertheless a fact worth noting…

The War Years

The Japanese Occupation arrested the development of publishing. Only a few papers, whether pro-resistance or pro-Japanese, were published during this time. The highly volatile nature of the political conditions was reflected in the character of the papers themselves—as, for instance, in the anonymously mimeographed pro-Japanese ‘publication’ called Visayan Press. Circulated in Cebu in early 1942, this was a single-sheet bulletin that hailed the advance of the Japanese forces.

The resistance paper of Cebu was Kadaugan, founded on October 11, 1942. Established by Cipriano Barba, this small tabloid lasted until 1943, when it was superseded by The Morning Times, a makeshift guerrilla organ edited by Pedro Calomarde and printed on a small Chandler machine in a cave in the mountain barrio of Kang-ando, Barili.

The Japanese mouthpiece was Visayan Shinbun, ironically subtitled ‘Independent Filipino Publication.’ Its first issue came out on July 19, 1942. Published by the Manila Shinbunsya and edited by Napoleon Dejoras, it was superseded in 1944 by the Cebu Times, which maintained the same format and frequency, except that it not longer carried any name in its editorial box. Both the Kadaugan and Shinbun published occasional literary pieces in Cebuano and English.

In 1945, with the return of the Americans, came Free Philippines, the local edition of the nationwide news bulletin published by the United States Information Service. The Cebu edition of this English paper, which was distributed free, came out twice a week and was published by the USAF Philippines Civil Affairs Unit 15, with Lt. Col. P. W. Scott as commanding officer.

Several papers were established and some old ones were re-issued in the Liberation period. The most notable of these were The Republic, founded in 1947… ; Vicente M. Florido’s Bag-ong Adlaw (1946-1947), printed in Carcar; and Natalio Bacalso’s Lamdag (1947-1950), printed in Manila.

Among the English tabloids founded after the war were Angel C. Anden’s The Pioneer Press (1946) and Napoleon Dejoras’ The Daily News (1951). These papers lasted for only a few years. In 1948, Jose Ma. Del Mar founded the Spanish biweekly, La Prensa, which lasted, on an irregular basis, until 1972 and was the last of Cebu’s Spanish-language papers.

A more interesting publishing venture was the Liwayway Publications’ Saloma which was founded in 1948 and lasted until the late ‘50s. It was a monthly series of pamphlets containing, in full or serial form, vernacular novels, mostly translations from Tagalog of such popular writers as Nemesio Caravana and Susana C. de Guzman. Saloma’s peak circulation of 22,000 is an indication of the avid appetite for popular fiction in the vernacular.

The post-war period

In the post-war years there was a growing decline in local vernacular publishing, a consequence of such factors as the consolidation in the use of English, the alienation of the educated class from literature in the dialect, and the facts of hard economics which weeded out peripheral publications. Also to be considered are internal factors, such as the failure of vernacular literature to break out of exhausted conventions, as suggested in the essays of Bienvenido Lumbera, Leonard Casper, and others. Vernacular writing, at its nadir, became associated almost exclusively with the lower classes, with rig drivers and housemaids, dismissed as popular pulp entertainment of minimal literary value—a far cry from the time when it was the language of poet-statesmen in the Visayas, the language heard at the old Teatro Oriente, where Manuel C. Briones delivered his eloquent speeches and the colegialas of Cebu played string instruments while Vicente Padriga and Joseph Arcache jousted in verse.

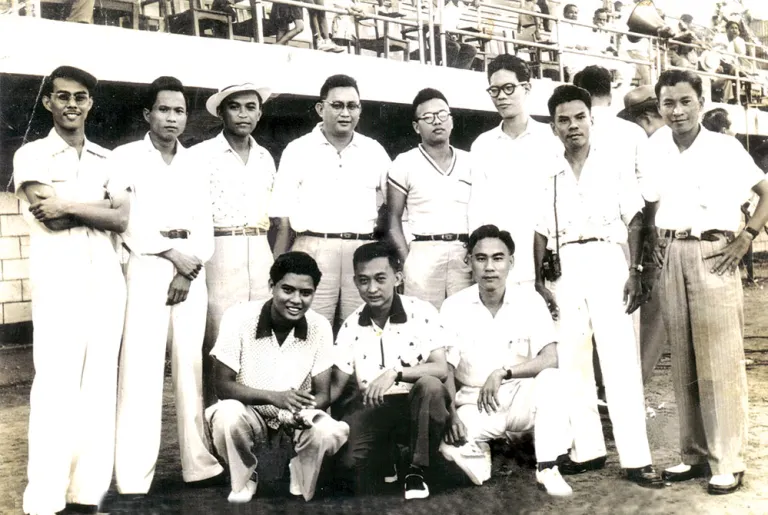

Golden boys. In the early 1950s, local media pioneers gave the local press a head start on other provincial press, even those in Luzon. In this rare 1954 photograph from the collection of Sun.Star Cebu columnist lawyer Manuel N. Oyson Jr., media pioneers gather in front of the newly constructed Abellana High School Stadium during a national interscholastic meet for public schools. In front (from left) are Wilfredo A. Veloso, Bernardo Bautista (reporter of Southern Star, later with Philippines Herald) and Hilario G. Embrado. Standing are (from left) Buddy G. Quintana (correspondent, Manila Times), unidentified, Nilo V. Cavales (Dumaguete City correspondent, Manila Times), Pocholo Romualdez (sports editor, Manila Times), Jose G. Logarta (Republic News), Ivar T. Gica (columnist, Morning Times), Clod Bajenting (Republic News), and Manuel N. Oyson Jr. (sportswriter, Southern Star).

In addition, the promotion of Filipino as a national language overshadowed attempts at reviving critical interest in Cebuano literature. Symptomatic of the situation is that many Cebuano writers feel that they are fighting a rearguard action against the advance of English and Filipino.

At this time, Cebuano publishing became the virtual monopoly of Manila publishing concerns. Lording it over all the rest is the durable Bisaya of Liwayway Publications Inc. In 1952, Bulaklak Publications Inc. of Manila started to publish Alimyon with a reported circulation of 30,000. Modelled after Bisaya, it was an entertainment magazine that published both Cebuano originals and translations from Tagalog. It ceased publication in 1963. The Manila Bulletin Inc. also came out with a similar magazine, Silaw (1961-1964), to cash in on the Cebuano reading market.

In 1963, the Foundation Publishing House of Danao, Cebu, started publication of Bag-ong Suga, a weekly vernacular magazine. Inferior in printing quality to Bisaya, though more hospitable to experimental writing, it stopped publication in 1971.

Today, there is only the Bisaya. It is the most popular vehicle of Cebuano writing but the fact that it is a commercial magazine means that its editorial policies are often bound up with restrictive business considerations. Hence, the complaint of many writers that there is at present no outlet for ‘serious’ and experimental literary works. What this points up is the need for more outlets and alternatives, for more sympathetic editorial policies, and for initiatives on the part of universities and associations to promote Cebuano vernacular writing.