The elliptical man

U.P. System’s Gawad Plaridel

The elliptical man

MAYETTE Q. TABADA

Sept. 25, 2008 ( CJJ4 )

This article originally appeared in a UP College of Communication magazine devoted to the awardee and circulated during the awards ceremony.

IN the beginning was the printed word.

Growing up in Sibonga, some 50 kilometers south of Cebu City, Pachico A. Seares recalls being a wide reader. This preoccupation was not unusual in itself as the town was as sleepy as any in the 1950s, and the young man nicknamed Cheking was not only the son of Ramon Seares Sr. and Purificacion Alicaya, public school teachers, but also distinguished by a total lack of athletic prowess.

But as with all first loves, the passion for reading, which was to spawn Cheking’s enduring affair with writing, flourished at great cost. To reach the town’s two bookshelves, the diffident, gangly teenager had to enter the town hall, walk up flights of stairs and go down corridors, and run the gauntlet of officials and petitioners hanging around public offices.

Years later, though Cheking rarely strayed far from the radius of the Sun.Star Cebu newsroom where he was editor-in-chief, he attempted to give back to his hometown what he found after losing himself among those twin bookshelves.

The Ramon Seares Sr. Public Library is a modern but modest one-story structure that fronts the town plaza, abuts the public waiting shed and faces the Church of the Nuestra Señora del Pilar of the 18th-Century painted baroque ceiling.

Although Cheking briefly practiced law in Sibonga, served as the municipal secretary (“the Little Mayor”) and produced the municipal newsletter while waiting for the Bar results, he sees the RSS Library as a solid testament to his parents’ contribution to public education and his own love for the printed word. Its location, he muses, guarantees that no one in town needs ever again to brave the crowds to get his hands on a book.

185 awards

Now approaching its 26th year, Sun.Star Cebu, along with its sister publications, Sun.Star Superbalita [Cebu] and The Cebu Yearbook, is housed in a three-storey building Sun.Star Publishing Inc. constructed on the lot it purchased along P. del Rosario St., part of the downtown university belt in Cebu City.

The hours before noon usually find the central newsroom deserted and hushed, save for the whirring of the air-conditioning unit. But the odd editor or reporter working unusually early at his work station has been known to get startled when the dailies’ editor-in-chief silently materializes near one’s elbow, rolling the gravel in the familiar mumble that’s already dissecting the way a news “head” is phrased or an angle opened by reported facts in the day’s issue.

But what Cheking regards as his mellowing as a newsman lies in the elliptical orbit of perceptions.

At 67, after logging in four decades and counting in Cebu journalism, Cheking admits that he’s mellowed a bit. He doesn’t think anymore of the paper while he’s taking the shower or eating his meals. He finds time to sip coffee; often totes a book that’s not related the slightest to the business of news. (Samples of titles he’s been reading lately: Why Presidents Lie: A History of Official Deception and Consequences by Eric Alternman; What I Saw at the Revolution by Peggy Noonan; Wallflower at the Orgy by Nora Ephron; Big Ideas: The Essential Guide to the Latest Thinking by Jones Harkin.)

He even oversees certain domestic arrangements, such as keeping the family’s three male dogs in front while the two bitches are at the back of the house (“You know why I keep them separate? They’re all relatives.”).

But what Cheking regards as his mellowing as a newsman lies in the elliptical orbit of perceptions. To government officials and society mavens frustrated in their efforts to get him in their guest list, he is the mulish journalist who will not sit across a news source in any social setting unless there is a story that can be reported in the next day’s edition or at least some idea that will lead to an interesting story for the paper.

To students of the University of the Philippines in the Visayas Cebu College, where he teaches “Media Issues on Social Responsibility” and “Journalism Law and Ethics,” he is the mentor who, along with other Sun.Star editors, steers them past theory to research and write civic journalism reports that find print in Sun.Star pages, even garnering a nomination for a special report award in the Cebu Archdiocesan Mass Media Awards.

To Sun.Star colleagues, the newsroom is where Cheking is not just in his element. It is where he is at his most salient.

In 1994, Sun.Star Daily (as the paper was known then) made the move from the rented premises it first occupied along Jones Ave. to the present permanent address at P. del Rosario St. It was a long way from the old office, where some reporters had to sit on bundles of old newspapers or old phone directories because the chairs could not be adjusted to ease the typing.

The upstart paper infused “new hope, a chance to do something new and make a turnaround for local journalism,” Cheking recalls of 1982, when Sun.Star Daily joined the community press in Cebu.

Then The Freeman editor-in-chief, Cheking was advised that a new daily would take at least five years to stabilize, given the competition presented by many dailies and weeklies, including his own paper, the industry leader at the time.

But Cheking defected anyway. Seven months after it put out its maiden issue, Sun.Star Daily caught up with the circulation and readership of The Freeman. Within two years of its launch, Sun.Star Daily’s finances had pushed it to the lead while many competitors—Morning Times, Daily News, The Republic News, People’s Journal, Cebu Newstime—wrote 30.

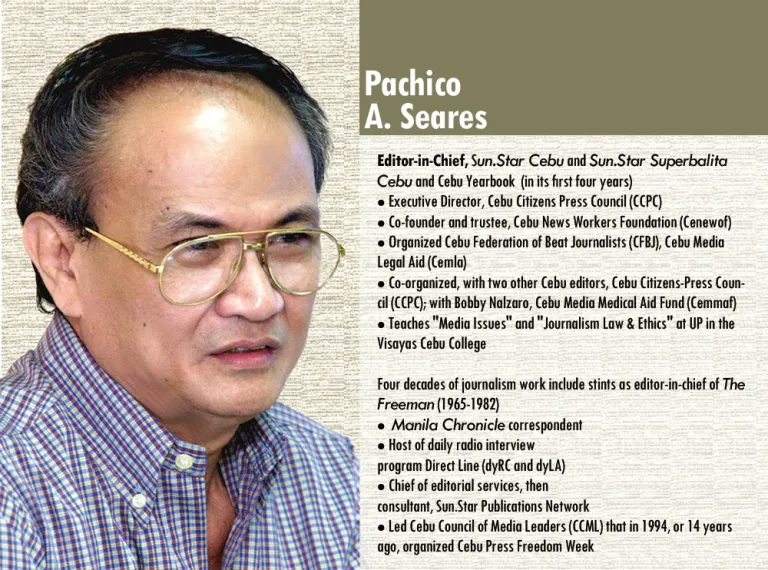

In his watch, Sun.Star Cebu has won 185 journalism awards. He has not only turned it into the most multi-awarded community paper in the country; the English daily and Sun.Star Superbalita [Cebu] are currently the largest circulated regional newspapers.

In the early ‘90s, the Philippine Press Institute packaged a seminar composed entirely of Sun.Star Cebu staff, from business managers to editors, as speakers to spread in the regions the success of this community paper.

Wire act

After writing an editorial or column, Cheking frequently relaxes by watching his pet hammerhead sharks. One of the four has a particularly aggressive streak that drives it to attack the other sharks, churning the waters of the family aquarium in its frenzy.

Largely vicarious, this taste for violence is reined in by Cheking, perhaps through the man’s regard for the dispassion of reason, perhaps by the discipline imposed by his legal training (he graduated magna cum laude from the Gullas Law School of the University of the Visayas). While he admits that his 1965 recruitment as managing editor of The Freeman “put lawyering out of mind,” he says that a knowledge of and experience in the law helped him in evaluating stories and avoiding litigious content and unnecessary lawsuits.

But more than lucidity and legal acumen seem to have aided Cheking in keeping Sun.Star Cebu’s balance throughout episodic attacks against its credibility. From the start of its publication, the paper was targeted by the political opposition and militants as a member of the crony press since its major stockholder, Anos Fonacier, was a well-known associate of then President Ferdinand Marcos.

A more virulent public campaign attacking the paper’s independence and responsibility was later mounted in the late ‘90s and early 2000, when Cebu City Mayor Tomas Osmeña accused the paper of being a mouthpiece of his political rival, Alvin Garcia, a member of the family that bought majority of Sun.Star Cebu stocks in 1986. The mayor’s attacks dovetailed with the prominent campaign of a competing paper to promote “independent papers” that did not “kiss the ass” of its political owners.

Although Cheking admits that the paper’s credibility was “attacked,” he says that the boycott campaigns “failed to erode” the public’s trust in Sun.Star Cebu as an exponent of “good journalism.”

“Sun.Star Cebu survived the tag of cronyism. There was no dent in the paper’s circulation and advertising.”

Though he entered journalism at a time when most of those who invested in media held political and business interests, he advocated, first in The Freeman, later in Sun.Star Cebu, a recognition among the owners of the inevitable in the post-Edsa 1 shift of power: “Media ownership as a political tool was a thing of the past. The Cebu public called for papers to be ‘independent.’ They did not want papers to promote only their owners’ interests.”

Cheking convinced Sun.Star owners that “good journalism is good business.” A paper that sought to always raise the level of its professionalism earned the public’s trust. This reservoir of public goodwill translated into patronage in street sales, subscriptions and advertising.

He credits Sun.Star president and chairman of the board Jesus “Sonny” B. Garcia Jr. for supporting the tenets of freedom and accountability and espousing what the publisher calls “authentic journalism.” Sonny, Cheking says, is also responsible for the visionary thrust of the Sun.Star Media Group that led to its network of community papers and its hugely successful website (www.sunstar.com.ph).

To uphold the tenets of public service and professionalism, Sun.Star journalists signed and swore to the 1991 Sun.Star Code of Standards and Ethics before then Supreme Court Chief Justice Marcelo B. Fernan on Aug. 24, 1991. On Feb. 7, 2004, newsroom workers and executive publisher Gina G. Atienza signed the Amended Code before Supreme Court Chief Justice Hilario G. Davide Jr.

“To the Sun.Star public, the Code is one specific document with which it can hold Sun.Star personnel accountable for their behavior as journalists,” Cheking wrote in his 2004 foreword to the Amended Code. “The Code is no guarantee of good journalism and ethical behavior… If for nothing else, the huge effort to become better journalists and better individuals is there.”

PJR reports’ issue of August 2008 devotes three pages on Seares’ Gawad Plaridel lecture

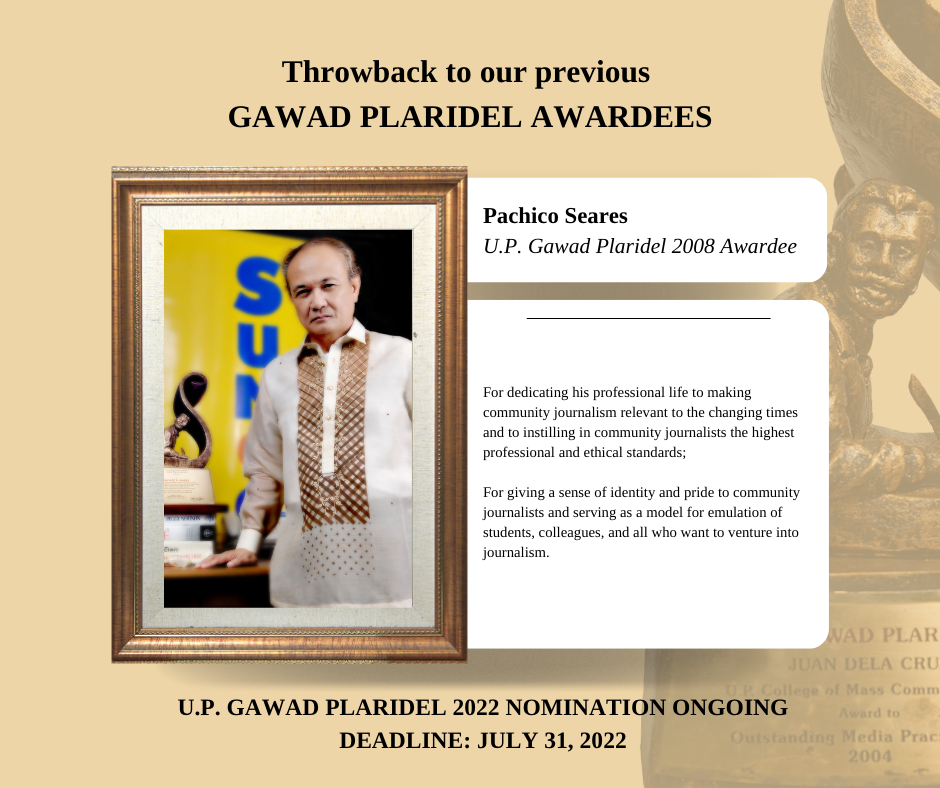

Seares’ dedication and credibility sustain public confidence in newspapers… His pioneering efforts have brought community journalism at par with the mainstream, including on-line publications. —Emerlinda R. Roman, president, University of the Philippines (UP)

His ideals and principles not only reflect those of Plaridel; they keep community journalism alive and running, with no intent of stopping the presses…’ —Sergio S. Cao, chancellor, UP Diliman

Seares’ influence in community journalism goes beyond the newsrooms… Truly, he is a modern-day Plaridel, a community media practitioner fit to be emulated and honored. May he continue to inspire and serve the people. —Elena E. Pernia, dean, UP College of Mass Communication, Diliman

Journalists don’t fade

At 130-140 lbs, Cheking today is a wisp of his former beefy self during the early halcyon days of his watch as newsroom chief. To the more imaginative, he has a physical transparency that borders on an ellipsis, a manner of speech that obliquely refers more to what is left out than to what is left in.

That is a whimsy quickly dismissed after taking a closer look at Cheking’s game plan. During the formative years of the paper, then its period of stability and growth, he has been introducing concepts on standards and values, staffing structure, and newsroom management, adopting and perfecting those that work and rejecting those that don’t. At an assembly of Sun.Star employees, the paper’s chairman called him “a great innovator.”

For the past three years or so, Cheking has been preparing for the transition in the newsroom. Leaders prepare best for the future by encouraging emerging ones and setting in place processes to continue “keeping the spirit of competitiveness and striving for excellence.”

Among the best newsroom practices that he is compiling are the marketing and advertising sections opened in the paper. Aside from the in-house policy curtailing marketing from influencing editorial decisions, Cheking recently prepared a brochure of tips orienting the paper’s marketing department and its clients on how to legitimately get into editorial pages.

“Media literacy is one way for the paper to show its kinship with the community,” Cheking says. The central newsroom campaign includes features on how readers and sources can get to know their paper better; explanations on how news stories and photographs are treated (as well as giving space for readers to comment on the paper’s news values and treatment); and seminars, usually held during Cebu Press Freedom Week, to expose campus journalists and journalism teachers to the actual media culture.

Mutual literacy dialogues are also initiated by the Cebu Citizens-Press Council (CCPC) to enable the media to learn from sources and key sectors, as well as vice versa. Acknowledged by the Philippine Press Council and the Philippine Press Institute as the most active and effective in the country today, the CCPC was co-founded by Cheking and two other Cebu print editors. With members from business, the religious and the academe, as well as print and broadcast journalists, the CCPC, which Cheking leads as executive director, helps defend press freedom by promoting accountability among journalists.

Beyond the newsroom, Cheking co-founded with the late Concepcion G. Briones the Cebu News Workers Foundation (Cenewof), which led to the formation of the MBF Cebu Press Center and the Cebu News Workers Cooperative (NewsCoop). Cheking also helped to organize the Cebu Media Medical Aid Fund (Cemmaf) and Cebu Media Legal Aid (Cemla).

The Cenewof oversees the finances of the Cebu Federation of Beat Journalists (CFBJ), an umbrella organization of different beat reporters’ groups. Cheking aims to also organize Cebu editors. Cheking sees the potential of the news workers’ blocs to take a stand against repression or abuse from whatever source.

Offered a two-week international cruise by the Board on Sun.Star Cebu’s 20th year, coinciding also with his 20th year as its editor-in-chief, Cheking gave a trademark bark of amusement, befuddled by the notion of staying away from the newsroom that long.

Asked if he had not really spared any thought of retiring after four decades in newspapering, Cheking says that he has always found it “reinvigorating” to check the day’s issue every morning: “I ask myself how we could have done it better, and then try to really do it the next day.” But he thinks a leave from his hands-on work at the news desk will allow him to do other aspects of journalism “without being chief of anything.”

When he will no longer be called upon to be “a journalist first, a lawyer second,” the man from Sibonga concedes that, for the past 40 years, he has been reading books in “bits and pieces.”

“I might finally get a chance again to read a book in one sitting.”