Snapshot of days past: Here’s OCS aka Orly — and Johnny B!

Passage

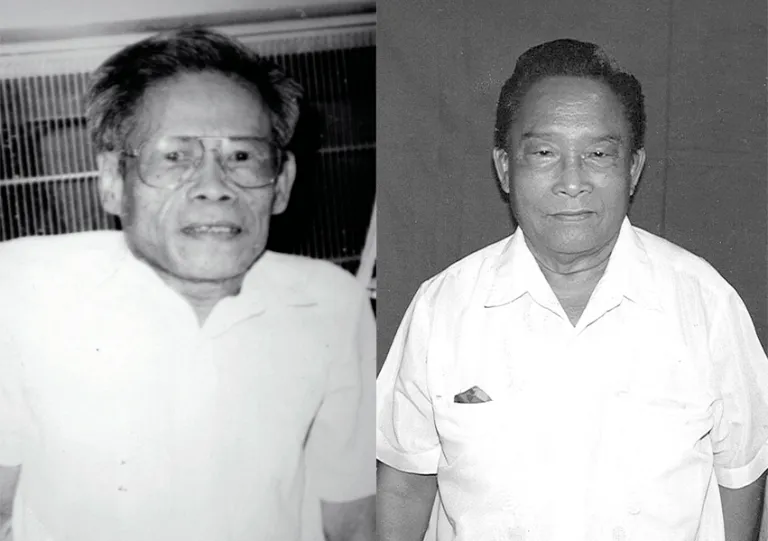

Orlando C. Sanchez and Johnny Bitang Sr.

Snapshot of days past: Here’s OCS aka Orly — and Johnny B!

PACHICO A. SEARES

Sept. 24, 2015

Take care of all your memories… for you can’t relive them.” -Bod Dylan

ORLANDO C. Sanchez and Johnny Bitang Sr. were my colleagues in The Freeman and Sun.Star. As their editor, I had worked closely with them, when the going was tough and journalism was both arduous and fun and better things were still to come. Mitch Albom wrote in “For One More Day” [2006] that “sharing tales of those we’ve lost is how we keep from really losing them.” Even better, tell the stories, share those memories before the mind closes its doors.

Orlacsan (1928-1994)

As sports editor of The Freeman from 1965 to 1982 and Sun.Star Cebu from 1982 until he died in 1994, Orlando C. Sanchez was the name in each paper’s staff box and the byline of his stories. To athletes, sports fans and readers and his friends, he was Orlacsan. The sign on the street named in his honor in his native city, Mandaue, says “Orlacsan Street.”

Widely known for generosity to athletes who weren’t getting enough subsidy from schools or business companies, he also helped officemates and colleagues in journalism who at the time had to grapple with deadlines and the hard times.

He had a small room—within the editorial/front office in The Freeman and in a corner room in the editorial section of Sun.Star— because he was the only journalist who worked and slept there.

Aside from handling the sports pages, he was “graveyard editor” who’d do changes on Page 1 if a big news event would break out after all other editors had left the building. An anecdote, maybe apocryphal, was that he was dating a girl in a hotel across the street when a multiple-alarm fire broke out and he had to be called back to the newsroom.

Hoarding

Not only was his room small, it had to bear with his propensity to hoard all kinds of reading materials, a passion that would clash with my duty not to convert the work area into a firetrap. I would talk with him to “clean up, remove the fire hazard” and, routinely have fire department people inspect the office, with their report later prominently posted on his door. To no avail.

Finally, we came upon a solution reached tacitly. Each time he’d leave for an out-oftown sports coverage or conference, I’d have his room removed of clutter, with the trash dumped and other materials boxed and stored elsewhere. He’d come home and keep quiet when he’d see the result. Not to my surprise, he didn’t even bother to go near the boxes we had put away.

Orlacsan was a bachelor but it wasn’t why he’d visit his comfortable home only once a week. He was one of few people in the world who could sleep more soundly with the printing machines roaring within earshot and the smell of printer’s ink dominating the air than in a quiet, sanitized room elsewhere.

When awakened for a “stop-the-press” story, he’d curse in Orlacsan fashion—expletives in colorful Cebuano-Bisaya—but everyone knew he really didn’t mind. He even loved it, especially the morning after when he’d see his work bannered on front page.

Johnny B (1923-2000)

Johnny Bitang—photographer of The Freeman, then Sun.Star Cebu—would make bearable the beat reporters’ waiting, often long and tedious, for the news source or event. He’d crack jokes or play the piano, if there was one at the site, and between snatches of popular tunes, he’d relate his experiences as a photographer: how he would have a ceremony reenacted by VIPs when he showed up minutes late or how he’d direct a senator to face this way or a city mayor to move from here to there.

It was his way of telling it that would send his colleagues to fits of laughter.

—His idioms and descriptions: “inside the job” or “mute and academic.”

—The reference to himself in the third person: “Si Bitang sigi lang gihapong click, click” (every time, photographers were sent out of a room for an executive meeting, he’d keep shooting, undaunted by the shooing order).

—The way he’d use his son (fellow photographer Mario Bitang) as the “straight guy” in the storytelling: “Do (for ondo), unsa to’y atong kape sa balay, pareha sa kang ‘Torni nga coffee?” (Lad, what was our coffee in the house, the same as Attorney’s coffee?)

Press freedom

Johnny B was the only journalist I know who questioned an editorial decision and called it “violation of press freedom” and “dictatorial” right in my face, not at the water station or in some coffee-shop or bar with the boys. I hadn’t used a photograph he submitted, showing a politician cutting a ribbon at a ceremony. “Unsa man ni, ‘Torni,” he growled, “violation of press freedom man ka. Akong gisaad nga ang retrato moguwa karon apan wa man lagi. Dictatoryal ni, Torni.”

(What is this, Attorney Seares? You are committing a violation of press freedom. I promised that the photo would come out today, but it didn’t. This is dictatorial, Attorney.)

One couldn’t be angry with Johnny B even though he sounded as if he was about to mount a coup. That’s the kind of man he was, one you believe would rather share a laugh than trade barbs with you. I explained how editorial decisions were made, why they were mostly made by one or two editors but who’d be accountable for what they decided—and why that specific photo failed against a better, more timely photo (which was also his).

Johnny B went about his job much like the way he rode his motorcycle: with his bulky frame on the comparatively small and frail-looking vehicle, at times he’d sway and swing too far to one side, threatening to fall, and yet keeping his seat and going forward, on to his assignment, all the while looking amusedly at the world. Later, he’d explain a long-winded route to preface a request for gas refund or why he shot the dead man at the morgue and not at the crime scene, now deemed classic excuses in Sun.Star newsroom history.

<<< Related posts