Messenger is silenced: The murder of Jessie Tabanao

Killing, harassing journalists

Broadcaster and Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency 7 spokesman Jesus “Jessie” Tabanao, 35, lies dead on Escario St., Cebu City

Messenger is silenced: The murder of Jessie Tabanao

JOEBERTH M. OCAO

July 15, 2017

IT was the eve of the 2013 Cebu Press Freedom Week and The Freeman junior reporter Jessa Agua had just won the Miss Press Freedom title. She and some colleagues in the industry had just pulled out of a restaurant where they were celebrating when news broke that radio anchor and Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) agent Jesus “Jessie” Tabanao had been gunned down two blocks away from the hotel where Jessa won her crown.

“That was one of the hardest blows as a media practitioner and a friend. What was supposed to be a happy celebration of my victory that night turned into a nightmare. The husband of my close friend was set to join our simple celebratory dinner and fetch his wife. He never came … My friend was eight months pregnant, and she just lost her husband. I will never understand how painful it was for her,” Agua recalls.

Tabanao sustained five gunshot wounds to the back, which killed him instantly. Before his death, he had hosted dyRC’s “Police Line-Up” and co-anchored “Drug Watch,” the station’s anti-drug advocacy program.

Two years later, his killer remains free.

Criteria

No direct link was established between Tabanao’s death and his work in radio, but the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) has classified his case as work related.

Under the Terms and Principles of Analysis by which CMFR assesses a case, a killing is counted in the line of duty for so long as it finds “any evidence to indicate motives external to the person’s activities as a journalist/media practitioner.”

“The good or bad practice of journalism is not a determining factor. The case is classified as ‘in the line of duty’ whether or not the abuse of the journalistic role was what provoked the killing in the first place.”

Still, CMFR acknowledges a journalist “may be killed for reasons that have nothing to do with his or her work, such as personal or family feuds as well as other conflicts involving business or other activities not related to the role of the press and broadcast news media.”

“The monitor does not exclude a case even when there are reports about the poor quality of the work of the journalist killed, or other indications of abuse of journalistic power, corruption or conflicts of interest. A broadcaster may be reported to have been using his/her reports, columns, radio/TV programs for his/her personal gain,” it says further.

A case is delisted when “corroborated reports/findings show that there was strong, paramount motive that had nothing to do with the person’s journalism/media practice.”

CMFR says there have been only two cases of exclusion since 15 years ago, including that of a photographer found to have been working as a police asset and a columnist who was involved in a fraudulent gun sale.

With respect to its monitor, CMFR says, “anyone who works regularly in the media (radio, TV, and print) in its journalistic aspects (that is, reporting, interviewing, commentary and/or opinion), regardless of the quality or status of the work, is included.”

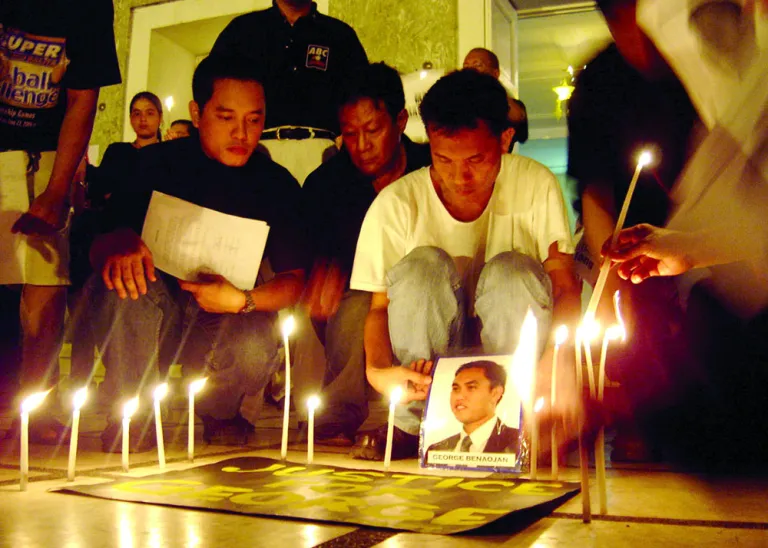

Media colleagues led by Cebu Federation of Beat Journalists president Joy Tumulak hold a prayer rally at the Capitol grounds after the killing of Bantay Radyo reporter and commentator George Benaojan in Talisay City in December 2005. Nestor holds a picture of his slain brother. (SunStar photo)

Cases

Tabanao’s death had a chilling effect on journalists already tormented by the violence inflicted upon other journalists in other parts of the country.

In 2009, 32 mediamen covering the election bid of Esmael Mangudadatu were massacred in Maguindanao with 15 of the 197 alleged killers from the influential Ampatuan family, including the alleged mastermind, Andal Ampatuan Sr. and his son, Andal “Unsay” Ampatuan Jr.

The suspects are now facing trial.

Ampatuan Sr., however, died last July after a bout with liver cancer, extinguishing his criminal but not civil liability, said Justice Secretary Leila de Lima.

Mastermind

According to CMFR, only 15 out of the 147 cases of journalists killed in the country since 1986 have been solved partly with the suspects convicted. So far, no mastermind has been prosecuted.

In Cebu, the list of unsolved cases dates back to 1984 when Vicente Villordon of dyLA, a critic of both government and communism, was shot on Dec. 28 outside the radio station. Twenty-two years later in 2006, the Philippine Star would report that former communist rebel Pastor Alcover Jr. had claimed Villordon and Leo Enriquez, his former colleagues in the CPP-NPA, were killed by their comrades.

A year later on June 1, 1985, another anchor of dyLA, Nabokodonosor “Nabing” Velez, was attacked by six men while he was watching his daughter compete in a beauty pageant. Two years later in 1987, news reporter Leo Enriquez III was shot dead outside his house in Mandaue City barely two weeks after suspected members of the New People’s Army attempted to torch his house.

In 1995, dyLA blocktimer Ambrosio Iyas and lawyer and broadcaster Geronimo “Boy” Creer were killed just two months from each other. Iyas was shot at his house in Lapu-Lapu City at the height of the elections while Creer and his lover were stabbed dead near the corner of Sanciangko and Pelaez Streets in Cebu City.

Police arrested one Jecknel Inso in relation to Creer’s death, but he was eventually released after prosecutors failed to present witnesses.

Closure

In more recent history, three local cases reached the courts and found closure–the killing of The Freeman and Banat News photographer Allan Dizon in 2004, Bantay Radyo reporter George Benaojan in 2005, and dyRF anchor Elpidio “Jojo” dela Victoria.

When he was killed, Dela Victoria was market administrator of Cebu City and served as project director of the city’s Bantay Dagat Commission. His work with the commission, particularly his vigilance against illegal fishing, was among the motives considered.

In 2006, two years after Dizon was shot dead in Cebu City, the Regional Trial Court convicted Dizon’s neighbor, businessman Edgar Belandres, but an appeal to the higher court reversed the ruling and set Belandres free.

Also two years after Benaojan was shot in Talisay City, the Regional Trial Court convicted former professional boxer Roberto “Dinky” Jagdon of homicide.

Just months after Dela Victoria was shot in Talisay City, the court sent policeman Marcial Ocampo to jail for 40 years for murder. The case was elevated to the Court of Appeals and remains pending there.

So far, the only journalist whose death was considered job-related was Republic News editor and columnist Antonio Abad Tormis who, at that time of his murder on July 3, 1961, was writing commentaries on graft against Cebu City treasurer Felipe Pareja, the mastermind of his killing. Pareja and the gunman, Cesario Orongan, were convicted and imprisoned for the crime.

Responsibility

In 2014, journalism professor and CMFR deputy director Luis Teodoro wrote that the culture of impunity—evident in the State’s failure to punish killers of journalists, human rights defenders, political and social activists, priests, reformist local officials, and judges and lawyers–-nurtures a setting that emboldens those who want these people silenced.

“Under these conditions, the killing of journalists is likely to continue, even as the slow progress of the trial is being rightly or wrongly interpreted by those who wish to silence journalists as a sign that they can, like the hundreds of other killers of journalists, escape punishment,” reads his piece for CMFR’s blog In Medias Res.

Tabanao’s killing in 2013—and the failure of police to find his alleged killer—is a recent case in point.

That fateful night on Sept. 14, 2013, Agua was celebrating her victory with Tabanao’s wife, Katrina, who, at that time, was just a month shy from giving birth to a second child. Two years later, Katrina is frustrated and exhausted, not only as a wife but also as a former journalist.

“It’s obvious. The case is going nowhere. After the filing of the case, I was closely following (the case). But unlike other cases I used to cover when I was in the media, grabe kadugay ang resolution sa kaso, especially because it was after the (7.2 magnitude) earthquake and naguba ang Hall of Justice,” she says. (The resolution of the case was much delayed because the earthquake wrecked the Hall of Justice).

“Then, at last, I was told when I followed it up through the phone nga na-file na sya sa court. I went there to check on the status and I was told (there was a) warrant of arrest.”

When she asked why, as the complainant, she had not been notified of the progress in the case, “They told me, we only give copies of the warrant to the police.”

The warrant was reportedly issued to the cops in Mandaue City because the suspect resided there. Katrina said she took the initiative of giving a copy to the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG).

Fourteen months after the Nov. 27, 2004 attack on newspaper photographer Allan Dizon, his neighbor Edgar Belandres (above) was convicted of his murder. But four years later, the Court of Appeals reversed his conviction and set Belandres free. (SUNSTAR FILE)

‘Scary place’

For Katrina, the world “is a scary place especially for people whose job is to tell the truth.” She advises journalists and future practitioners: Be careful because if something happens to you, the lives of the people who love you will be shattered. It’s as if they die, too, and justice will be impossible to get.

Echoing the call of CMFR and lobby groups, Katrina urges government to put an end to the culture of impunity and to ensure a safer community for all.

“To the authorities, do your job. Keep the streets safe. After Jessie’s death, until now, every time (I see a) checkpoint, I wish that there had been a checkpoint in Cebu,” she says, adding, “There is a need to focus more on the resolution of these (murder) cases because, for me, murderers are not afraid to kill because justice in this country is non-existent.”

For CMFR, though, this role does not lie with the State alone and that part of the responsibility for ensuring independence and assuring their own safety lies with journalists.

“Press and media independence, their capacity to provide the public the information it needs, and the safety of journalists are joined in the Philippines. The state has the responsibility of assuring the safety of all citizens. But the media community has the equal responsibility of enhancing its own independence and assuring its own safety. Media advocates have highlighted the need for ethics and responsibility in press practice as a way of ensuring the value of their service, one that will earn public support and vigilant defense,” it says.

Agua, while shaken, isn’t jaded and believes living up to the tenets of journalism is one way for a journalist to protect himself or herself.

“This profession, more of a calling, entails much courage. We tell stories that will make or break an individual/organization. Threats will always be there, which is why before you pursue a story, make sure that you get both sides so that there will be less chance of your being tagged as biased. Personally, it is part of my regular prayer that I may be guided in pursuing stories that will create good change without endangering my own life because as editors and veterans say, ‘No story is worth dying for.’ You have to make sure that you come out alive from any dangerous coverage: crime story, disaster story, politics. Because if you die, who will tell the story?”