Fake news inflicts more damage in social media. What can be done

Fake news and disinformation

Fake news inflicts more damage in social media. What can be done

MILDRED V. GALARPE

Sept. 21,2017 ( CJJ12 )

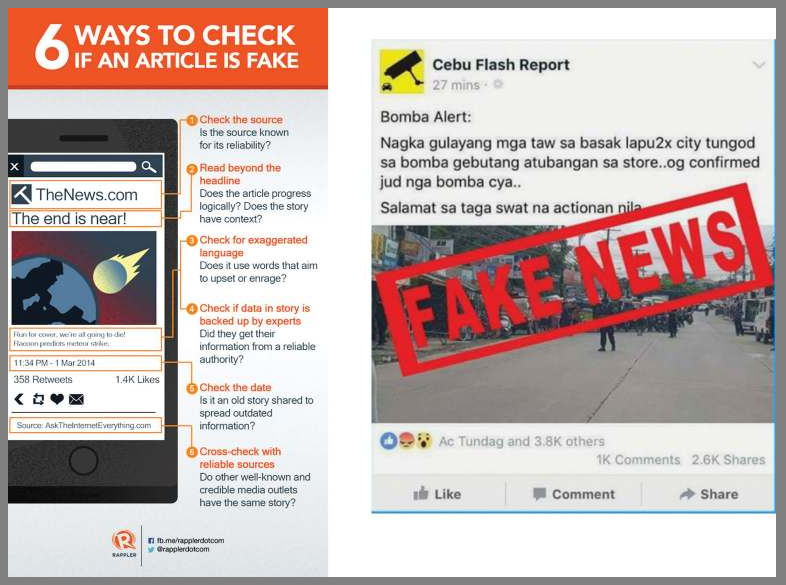

ON July 4, 2017, Cebu Flash Report (CFR) posted on its Facebook page a bomb alert in Basak, Lapu-Lapu City.

The post stated that people panicked after it was confirmed that a bomb had been found in front of a store in Lapu-Lapu City. It showed a picture of policemen on the street.

In 27 minutes, 2,600 Facebook users shared the 170-character post, 3,800 reacted and 1,000 more commented. Owners of the page deactivated the account later.

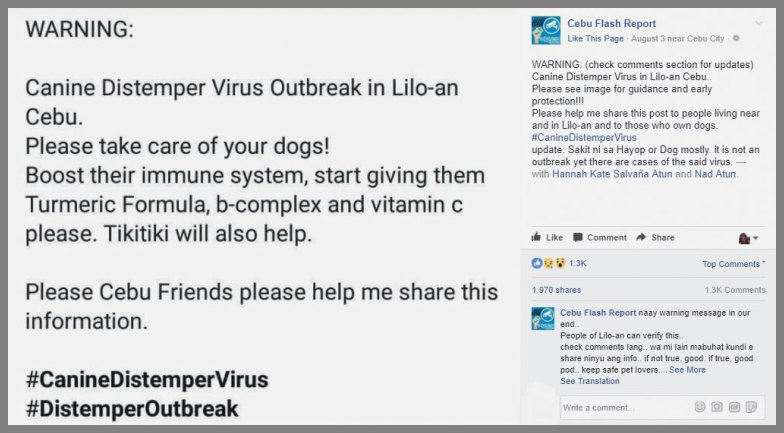

Barely a month after the bomb alert incident, active again on Facebook and sporting a new look, CFR posted about a canine distemper outbreak in the town of Liloan.

The post has been shared 1,970 times since it was posted on Aug. 3, 2017. There were 1,348 users who reacted on the post and 1,308 comments.

Both posts appeared on CFR’s Facebook page. Both headlines—“bomb alert” and “Canine Distemper Virus Outbreak in Lilo-an Cebu” are overly emotional and immediately catch the attention of readers.

Not a single source or official has been named as the source of the statements and declarations made in both posts.

No byline or author was indicated in the two posts, except for CFR, which appears to be a community of netizens.

Yuri Beluan, Lapu-Lapu City legal officer, and Liloan Mayor Christina Garcia Frasco in separate posts on Facebook called the posts “fake news.”

Beluan called on CFR to “not immediately post unverified details on Facebook to avoid panic.”

The bomb alert post came at a time when Cebu was hosting an Association of Southeast Asian Nations-related event and at the height of the Maute skirmishes in Marawi City.

Frasco, on the other hand, said the canine distemper post created unnecessary and unwarranted panic and distress, especially among pet owners, and caused undue harm and alarm in Liloan.

She said CFR presented itself as “Media/News Company” and as such should verify information prior to publication like true media companies do.

Bob Steele, senior faculty member and ethics group leader of Poynter Institute, explained that a news story byline personalizes the report so readers know someone is responsible for what’s reported and written. It allows readers to hold someone accountable for the story.

The disclosure of sources in the story is to show that the content came from official government sources, witnesses and experts, that it was not the creation or statement of a faceless source.

The “falseness” of content comes in different shades. Claire Wardle, research director of First Draft, identified seven types. These are

(1) satire or parody – no intention to cause harm but has the potential to fool,

(2) misleading content – misleading use of information to frame an issue or individual,

(3) imposter content –) when genuine sources are impersonated,

(4) fabricated content –new content is 100 percent false, designed to deceive and do harm,

(5) false connection – when headlines, visuals or captions don’t support the content,

(6) false context – when genuine content is shared with false contextual information, and

(7) manipulated content – when genuine information or imagery is manipulated to deceive.

First Draft is a non-profit coalition of more than 100 newsrooms and social networks and more than 35 journalism schools, building tools and resources to help people verify the information they are finding online.

Online threat

The ecosystem of fake news is not just on the “falseness” of the content, but it also involves the character the content is circulated—speed, scale and the nature of sharing.

A Field Guide to Fake News, compiled by Liliana Bournegru, Jonathan Gray, Tommaso Venturini and Michele Mauri, says fake news is directly related to the threat of its accelerated circulation on the web and online platforms.

It suggests that this circulation represents more than just the popularity of fake news like the number of likes, but also how it is shared, why it is shared, and the speed and scale it is shared.

The guide explores the use of digital methods to trace the production, circulation and reception of fake news online. It is a project of the Public Data Lab with support from First Draft.

In the case of CFR, it currently has 387,650 Facebook users who liked the page and 392,535 who are following it.

The Philippines is the world’s sixth largest country with active Facebook users of 63 million as of April 2017, according to wearesocial.com.sg, a global consulting agency on social thinking.

Wearesocial’s Digital in 2017: Southeast Asia, a study of the internet, social media, and mobile use throughout the region, showed that 60 million of the 103 million Filipinos are active internet users and spend an average of four hours and 17 minutes on social media via any device.

Of the 60 million active internet users, 86 percent visit social media sites, 52 percent are on search engines, 37 percent are checking email, 32 percent are listening to music and 10 percent are looking for product information.

Google ban

Facebook and Google are the two technology giants blamed for the proliferation of fake news.

Google recently announced that it had permanently banned nearly 200 publishers (website owners) from its Adsense advertising network last year after cracking down on websites misrepresenting themselves or their content.

Google has an existing policy against publishers with misrepresentative content like those on weight-loss schemes and counterfeit goods. The policy was now expanded to include sites impersonating news organizations.

Adsense is the life and blood of independent web publishers who rely on display advertising, and this is the main business model of fake news websites.

Facebook, on the other hand, introduced changes to its Trending Topics feature to better promote reliable news articles. The trending feature has been blamed for spreading false information.

It also updated part of its language policy which blocks ads on sites and pages showing misleading or illegal content.

The updated Trending Topics system now identifies groups of articles shared on Facebook instead of relying solely on mentions of a topic.

Recently, Senator Joel Villanueva filed a bill that would jail or fine people and companies that spread fake news. The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines also issued a pastoral letter telling Catholics to stop spreading fake news, “a sin against charity.”

Media’s task

Will any of these stop fake news? Jeff Jarvis, a blogger and journalism professor, said media should “bring journalism to the conversations that are already occurring on Facebook, Twitter, and elsewhere… we should be going to the social platforms, speaking the language there, respecting their context, and using the devices they provide—memes, video, photos, dancing GIFs if that’s what it takes — to bring journalistic value to the conversations that now occur without us.”

“We in media won’t get there until and unless we take responsibility for informing the public where the public is and for our responsibility in creating the vacuums exploited by the fake news factories.”

How can we stop fake news?

The Field Guide to Fake News strongly recommends for readers to share responsibly. Every social media user is an influencer within his/her own social network. Be familiar in spotting the telltales of fake news.

It recommended further to post and share only those stories verified to be true or from sources you know to be responsible.

Mildred V. Galarpe

Mildred V. Galarpe is SunStar’s digital strategy officer