The 12 CJJ print covers

The 12 CJJ print covers

Covers by Josua Cabrera.

Cover explainers by Mayette Q. Tabada.

Forewords by Pachico A. Seares.

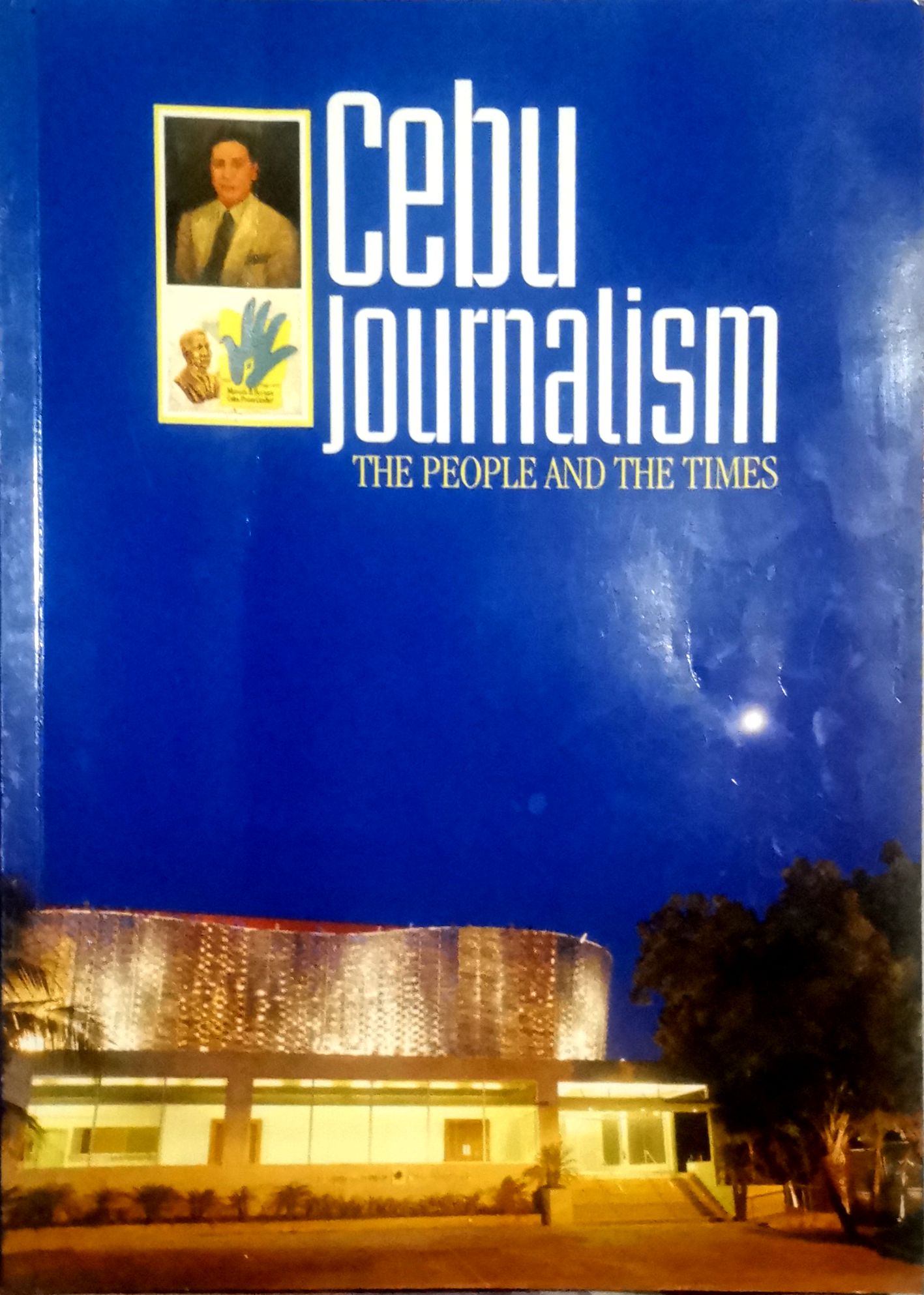

The cover

Tradition of contradictions

Contradictions are hospitable ground for changes.

The history of Cebu journalism attests to this. The first Cebu newspaper was published in the late 1800s, a period when the imperial dominated the local, when the suppressed lorded over the repressed.

Despite this eary marginalization of the native press, Cebuano writers were first in testing and later breaching the constraints imposed on Truth.

It is this tradition of unconvention that is embodied by two icons of the Cebu press. An enduring one is Antonio Abad Tormis whose fiery crusade against an official’s excesses ended wnen he was shot down by an assassin in one of Cebus streets.

A younger icon that has to test the vagaries of time and history is the Marcelo V. Fernan Cebu Press Center. Opened in 2003, the Center is envisioned to channel the centrifugal forces anchoring local journalism’s overarching ambitions: to reach out to the Cebuano community and the Fipno nation through its performance of professional and social responsibilities.

In short, the Cebu press aspires that its reach must extend its grasp.

Foreword

A work in progress

We wanted to honor past journalists in the form of a public exhibit that features their faces and what they did or have done for Cebu journalism. In 2003, I raised the idea to SunStar Cebu, then brought it up with convernors for an exhibit at the malls during PressWeek. Tougher than we thought. Not logistics (the Cebu Newspaper Workers Foundation and SunStar picked up the tab) but the tedious task of gathering materials made it so. We scaled down the plan and presented the exhibit to a smaller audience at the MBF Cebu Press Center during its inauguration on Oct. 25, not the originally wished-for September PressWeek run.

For year 2004, however; with more time, we are presenting the exhibit “Cebu journalism: the People and the times” a week before PressWeek at SM City and during PressWeek at Ayala Center Cebu before it goes back to its host site, the MBF Cebu Press Center:

It has more photographs than the first display in 2003 and, yes, a magazine containing some of the materials in the exhibit is published to go with. But then, as now, it stil is incomplete.

There are faces and articles one expects to see but doesn’t. We still had difficulty in gathering materials, especially on deceased journalists Some photos or data were already lost, or the keepers weren’t enthusiastic about sharing them with the public. As for current journalists, some were inaccessible or cooperated late.

The project will be a continuing work in progress as Cebu journalism evolves and its practitioners come and go in a never-ending cycle.

Modest as it is, the project is good enough. It has broken ground and set up structure.

With the invaluable help of such friends of the press as Globe Telecom and Cenewof, the project, no doubt about it, will continue in the coming years.

In the essential function of recording the evolution of Cebu newspapering and broadcasting, even as people and times change, I trust that the virtues of a free and fair press, which have mader Cebu the capital of community journalism in the country will endure.

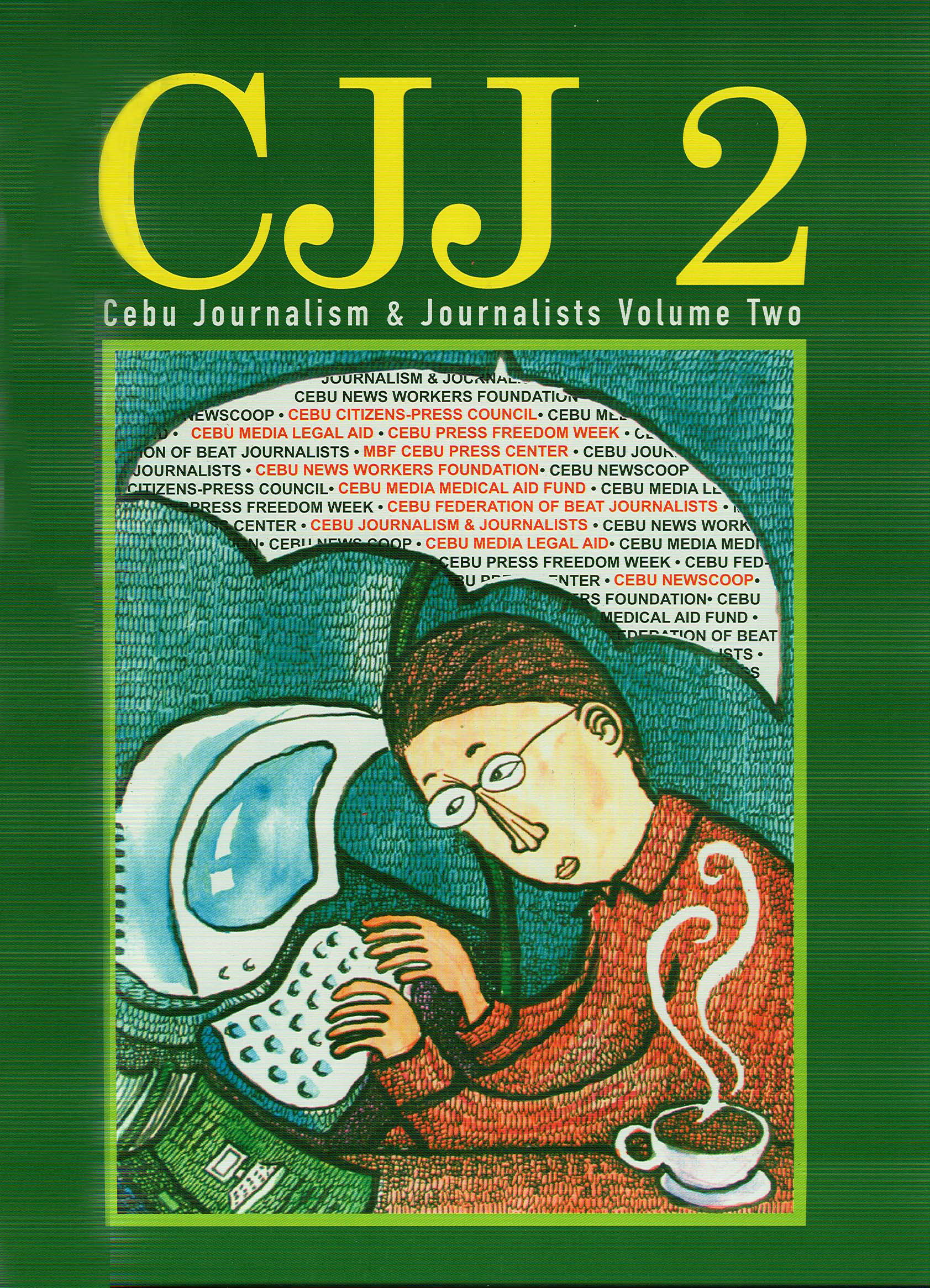

The cover

Sheltering sky

You have to be mad about doing your thing, with only a flimsy arch of spidery metal and vinyl covering you.

But there’s a real side to the magical Multi-awarded Josua S. Cabrera, editorial cartoonist of Sun.Star Cebu, executes the main points raised by SSC editor-in-chief Pachico A. Seares in this issue’s cover article.

A veteran of not just years but trends and tempers in community journalism, Seares is well-placed to count the local press’ blessings, many of which have to be enjoyed by journalists in the rest of the country.

For one, there’s a cooperative that encourages savings and supports news workers and their families through medical aid, housing and livelihood.

An association of lawyer-journalists backs up the legal support given by media companies to staff members sued for their writing or broadcasting.

Cebu has two responses to the call for continuing media self-education and professionalism: beat journalists organizing themselves for self-regulation, and a press council led by civil society that watches the press for lapses and oversights.

As it happens, whenever September 21 comes around, while the rest of the country commemorates one of the nation’s darkest chapters, Cebu media celebrate freedom over tyranny, solidarity over competition.

In a trade that’s thin on material rewards but generous with deadlines, pressure and responsibility, Cebu’s magic umbrella may not be so whimsical after all.

Foreword

Work in progress goes on

The first issue of the series in September 2004 was titled, “Cebu Journalism: The life and the times.”

This second edition, two years later, is renamed “Cebu Journalism and Journalists Volume Two”(CJJ2).

It is on track with its purpose: to put between its covers people, institutions, and activities that have helped bring Cebu journalism to what it is now: dynamic and thriving.

Few remember, if at all, what journalists chronicle history every day and yet so little about their work and themselves is recorded.

The same handicap of the first issue also bugged CJJ2: lack of time and resources to include everyone who deserves to be in the list.

As I said earlier, this is work in progress and will always be: each edition not ever complete, requiring a next edition and a next, and so on, as journalism evolves in flux, “a continuos movement of continual change,” as people and the years come and go. Except for those who died before 2004 and missed the chance, the featured journalists were their own sources. As they vouch for their stories, they attest to the things here about themselves.

Salamat to friends of the press

We thank those who helped make this project possible: Globe Telecom, Innove, and Cebu Holdings, Inc.

Their support affirms their faith in and hope for good journalism, their belief in a free and responsible press as an essential component of the community, and their commitment to the progress of Cebu and its people’s well-being.

Salamat kaayo to these true friends of the press.

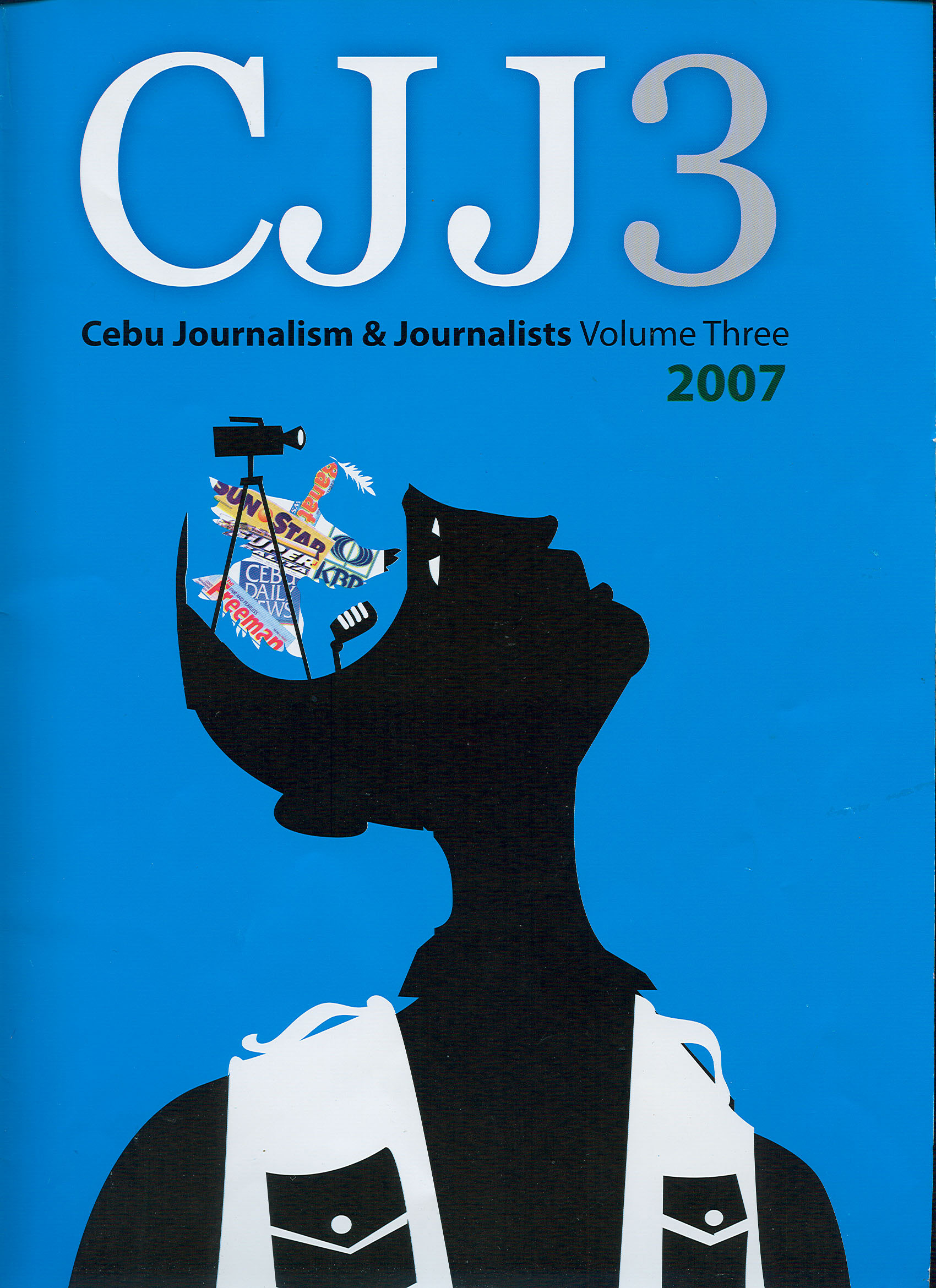

The cover

Set us free

Journalists are the new shamans. In the Tungas language of Siberia, the shaman is a spiritual leader who went into trance to cross over into another world so he could get information to heal his tribe of maladies and misfortunes.

In this age, the journalist, more than any knowledge worker, wields the power to transform. Using four platforms-radio, print, television, electronic media—-today’s reporters, editors and photojournalists spread information and analysis.

Whether spread through the airwaves, preserved on impermanent newsprint, fixed as indelible images, sent at the click of the mouse—news and opinion alter consciousness.

But more important than the channels is the journalist himself or herself. The press decides whether to wield this power for breaking down wall or erecting new ones.

As multi-awarded SunStar Cebu artist Josua S. Cabrera annotates his cover illustration, “Journalism’s essence is achieved when one has freed the truth from the walls of the mind.” In his heaven-directed gaze, Cabrera’s journalist reveals his intentions, if not his aspirations.

Foreword

And now edition three

CJJ3, the third volume of Cebu Journalism and Journalists, comes after first volume in 2004 and the second volume in 2006.

Someone asked if CJJ is an annual. Obviously not, as the gap between publication shows. There’s a common thread, though, in two of the three editions:CJJ1 in 2004 was conceived and produced when SunStar was lead convenor of Cebu Press Freedom Week, This year, 2007, SunStar is again lead convenor.

Is it a magazine or a book? It is a magazine at the beginning but eventually, it may evolve into a book. It has a book format and, maybe in the years ahead, it will be thick enough to qualify as one.

CJJ1 (Then called Cebu Journalism: The People and the Times) and CJJ2 each had a tandem: a photo exhibit of the journalism featured in the publication.

CJJ3 also goes with a photo exhibit but this time the subject is “Journalists at Work.” But the people behind CJJ are also the people who assembled and put up this year’s exhibit, with the help of photographers from the three English dailies-SunStar, The freeman and Cebu Daily News who conceived and produced a smaller version in 2006.

There are more journalists featured in this edition but it is by no means complete. It still is work in progress.

The goal stays: To keep some authentic record of Cebu Journalism and Journalists.

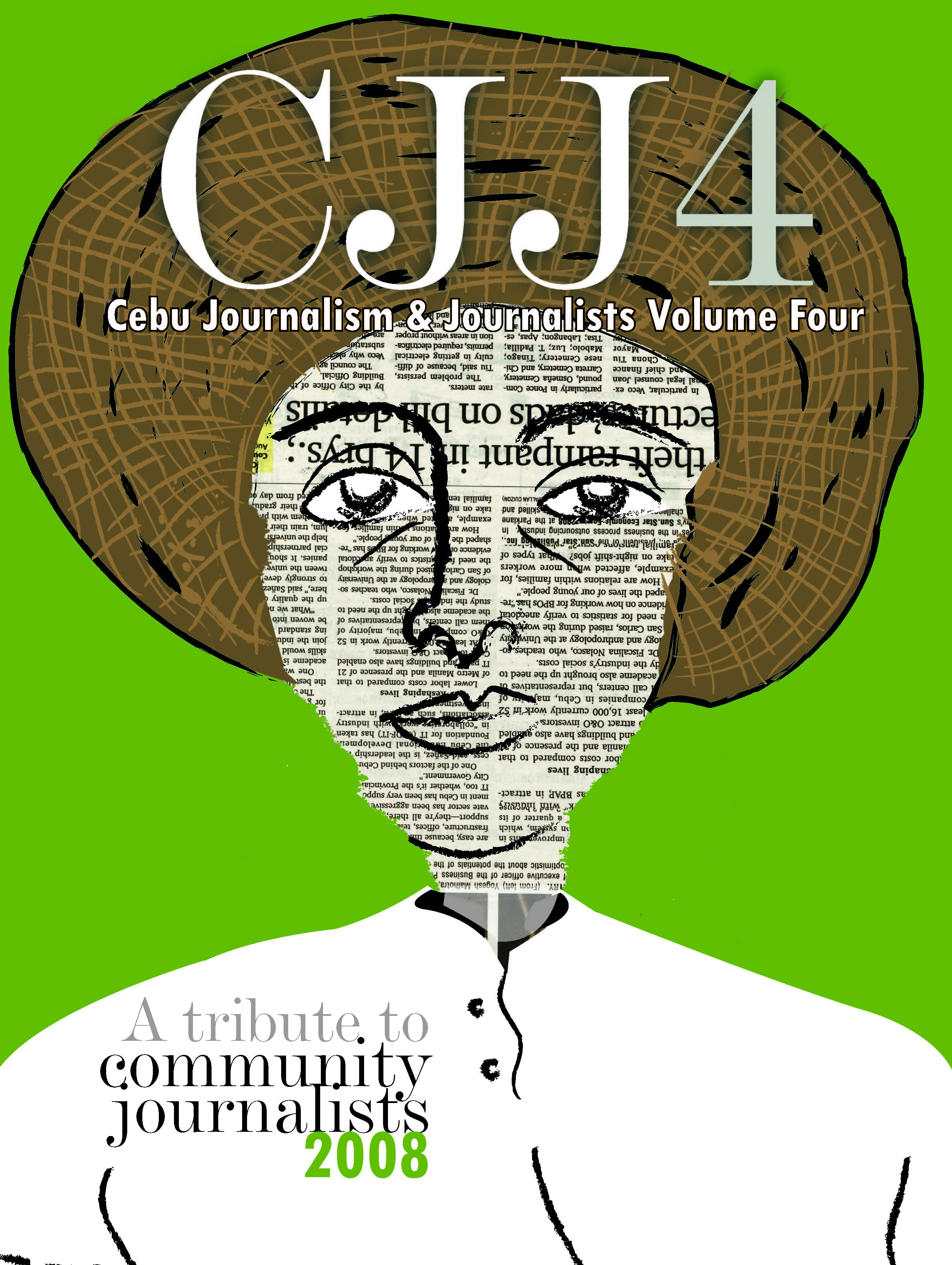

The cover

Coverage and community

More than any stakeholder, the community media must immerse itself in its milieu. This is the central message of the mixed media artwork created by Josua S. Cabrera for the fourth volume of Cebu Journalism & Journalists (CJJ4).

Creating his fourth cover for the publication traditionally released during the Cebu Press Freedom Week, Cabrera, award-winning editorial cartoonist of Sun.Star Cebu and president of Bathalan-ong Halad sa Dagang, combined his signature hand-drawn artwork with digital illustrations to portray a journalist in earth hues, visual metaphor for a communicator whose pen and heart are dipped in the grassroots.

Despite the challenges of competing with other media, particularly the Internet, the Cebu press should never sever its ties with the voiceless and powerless, the community that is its public calling, fountainhead of its relevance and credibility.

Through its monitoring as a watchdog, investigation and explanation through civic journalism, or promotion of causes through advocacy journalism, the Cebu media lives up to the patriotism of Plaridel.

In 2008, which is also its Centennial celebration, the University of the Philippines (UP) awarded the fifth Gawad Plaridel to lawyer Pachico A. Seares, editor-in-chief of SunStar Cebu and SunStar Superbalita (Cebu).

The Gawad Plaridel is the UP system’s sole award recognizing outstanding media practitioners espousing the causes of Marcel H. del Pilar, whose nom de plume, Plaridel, stood for crusading journalism.

Seares, hailed as a “modern Plaridel at the grassroots level” by UP, dedicated the Gawad Plaridel to his Cebu media colleagues, whose professionalism and integrity are committed to public service. In Seares’ words, “We should not just cover the community we serve, but we should also serve the community we cover.”

Foreword

CJJ’s modest goal

Cebu Journalism & Journalists has never claimed or pretended to be a complete record.

Its list of Cebu journalists doesn’t include everyone. Its few articles don’t tell the full story about Cebu journalism.

We have said CJJ is a work in progress. Most likely it will always be. Problem of space, time, and everything else one needs to put out a decent publication is a persistent pest.

Our modest goal is that one CJJ after the other will be of some use to the few people who might care to write Cebu journalism’s history.

At least, CJJ will leave something more than those few scraps of information that pre-war and early post-war journalists had left us about themselves and their work.

Tribute to community journalists

CJJ4 is a tribute to all journalists in the countryside, which Gawas Plaridel 2008 basically was, too.

As I said in the Plaridel lecture last July 4,2008 at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman, Gawad Plaridel honors community journalists everywhere shoes collective work has persuaded the UP system that smaller newspapers in regional centers and far-flung towns are a vigorous force, serving audiences that Manila-based broadsheets don’t target or can’t reach.

As I said to UP Diliman’s future journalists, a message inscribed at the Plaridel Gallery in the lobby of the UP College of Communication, there’s an exciting, if duanting, world out there for journalists who have grit, skill and passion for good and true journalism.

Community journalism will survive and endure.

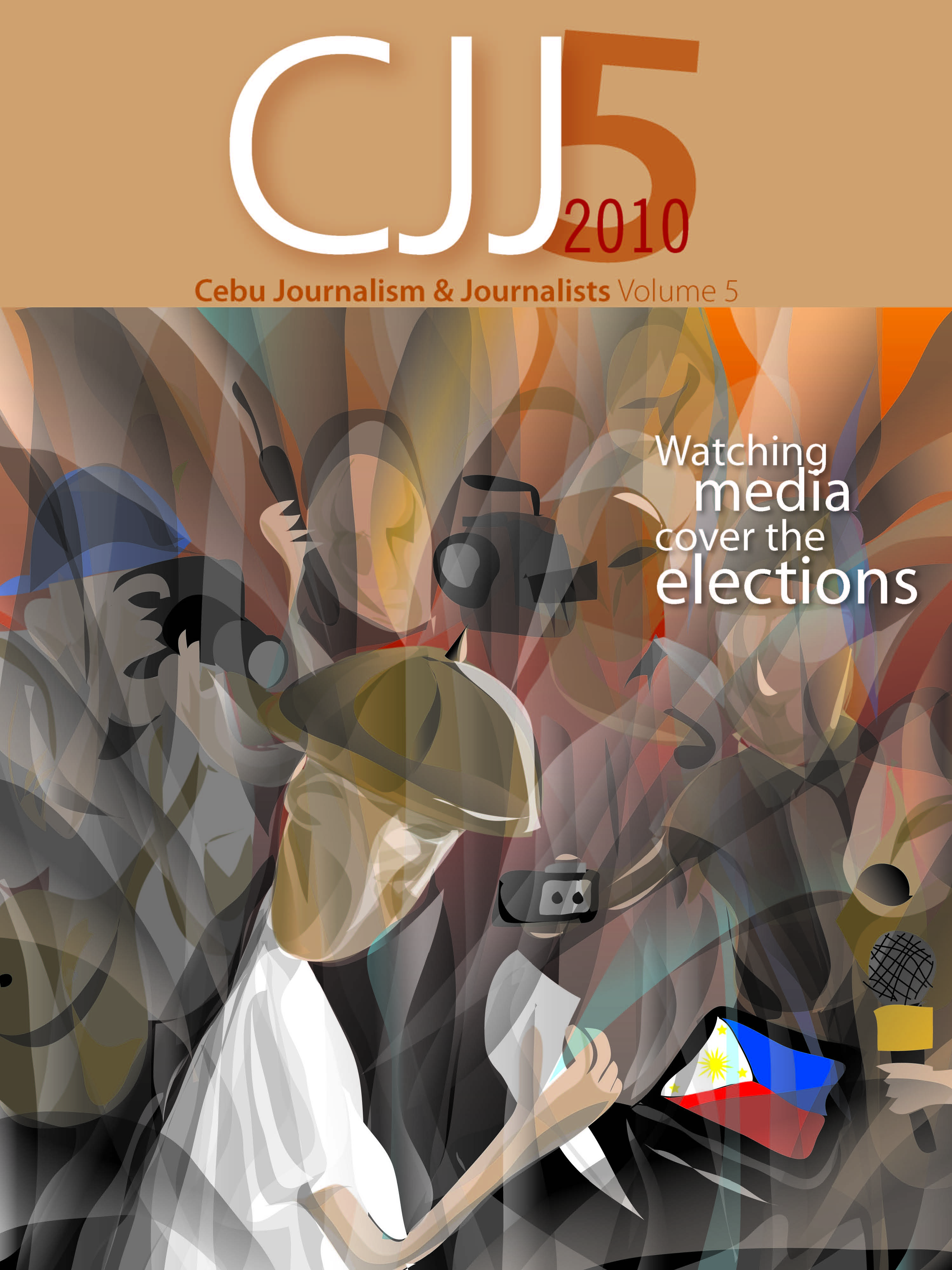

The cover

Modern Charybdis

Media is everywhere. No one can escape it.

In award-winning editorial cartoonist Josua Cabrera’s vision, the news media is a fearsome element of the age: everything significant is sieved through that omnipresent witness; whatever is sieved through this witness becomes automatically significant.

In the historic May 2010 election, traditional and new media jockeyed for vantage points to chronicle the country’s first automated election and the changing of the guards, from a discredited incumbent for one popularly anointed-by whom: the people or the press?–to usher in an era of changes. With so much power, how did the media acquit itself?

In the 2010 monitoring and scrutiny of media institutions and civil society, the national media and the Cebu tri-media met the challenge to clarify and educate through information, set agenda and deepen public debate through investigation.

More so than in the 2007 election, political candidates and parties, causes-oriented groups, civil society and individual Netizens used texting, blogging and social networking to shape the election agenda, indirectly altering the media balance of power and the flow and direction of media content.

Filipino voters, swirling in that vortex of politicians and media handlers, the news media, and a media-savvy civil society, may have felt they were in the churning in a modern Charybdis: immersed in a sea of societal issues but overwhelmed also by forces beyond their control; contested by contradictory competing interests; inundated by changes that later seem mere circuitous variations of the entrenched and immutable.

To survive being buffeted by the elements of this age, Filipinos must empower themselves through media literacy, jargon for navigation, a timeless skill that saved the ships of myth from entering Charybdis, ship-devourer, whirlpool of the gods.

Foreword

Past and present and beyond newsroom walls

A columnist in the Hearst newspapers, Arthur Brisbane, was offered a six-month vacation on full pay as reward for his dedicated and successtul work. He refused. According to this account, re-told in journalism schools, when media mogul Willam Randolph Hearst asked wny, Brisbane gave two reasons.

The journalist feared the consequence of not writing for a long time.”It might damage the circulation of your newspapers,” he told Hearst. “The second reason is that it might not”.

Cebu journalists who have stopped writing are dead or have shifted to other fields less stressful and more financially or intellectualy rewarding than media work. Their photos and bios occupy the last three sections of this publication.

Those who’re alive and well and have left writing as a job must have long ceased worrying, if they did, about the effect of their absence from media. Whatever they do now with their creative juices, they were once part of the work force that produced news and features stories, opinion pieces, and special reports.

They were part of the history of Cebu journalism and deserve space in any CJJ edition, along with those who’re alive and well enough to continue comforting the afflicted and afflicting those who deserves a kick in the ass.

Theme

“Past with the present” is also the theme of CJJ Gallery, the media section of Museo Sugbo. One sees there relics of the past (old printing equipment, antiquated microphones, or musty newspaper pages) and evidences of the present (practices and practitioners of today’s media). Glimpses of the old and snapshots of the new somehow tell the viewer how Cebu journalism has evolved the grown through the years.

You’re reading CJJ5, which also helps record that evolution and growth. Changes in the latest edition include reducing space for personalities to accommodate more articles and features.

CJJ, the magazine and the museum gallery, is among the initiatives of a group of Cebu journalists who believe that passion for journalism goes beyond producing newspapers and broadcast programs, outside walls of newsroom and studio booths, into the community of which they are much a part.

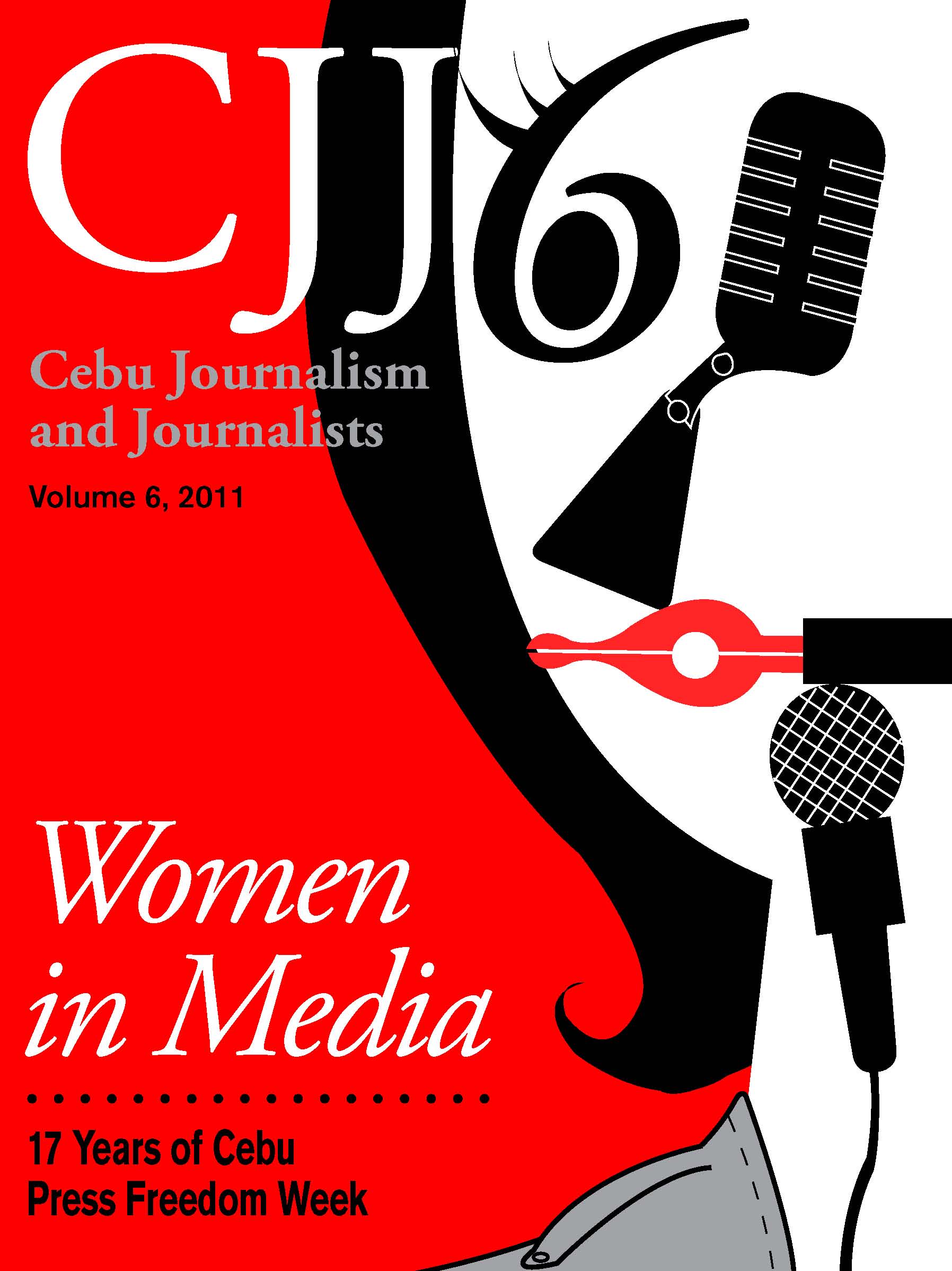

The cover

Cover girls & more

When examining women working in Cebu newsrooms, it’s a challenge to sidestep clichés. “You’ve come a long way, baby”—a vintage slogan for a cigarette brand catering to the liberated woman—sums up the flight from hobby to career, passion to profession, “news hen” to journalist (gender irrelevant).

The sixth edition of the Cebu Journalism & Journalists (CJJ) has on the cover an illustration by Josua Cabrera, SunStar Cebu’s art group chief. An editorial cartoonist whose visual puns have won local and national journalism awards, Cabrera shows a composite woman cobbled from the tools of communication: not just the traditional instruments of observation, documentation and examination but the convergence of technology that has, by increments, changed how we perceive and make sense of our worlds.

“Pretty Woman” or “Fatal Attraction”? How are newsrooms changing as domains where many of those sporting the pants are curvier and color-coordinated, a mix of the learned and the intuitive, not strange to the PMS myth (to decode, pick your favorite: pre-menstrual syndrome, post-menopausal struggle or perpetual maternal stress).

In newsrooms, which did not invent but elevated multitasking, are women—singletons, wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, friends, lovers—in or out of their element? Or is this line of inquiry following femininity’s tracts in a rough-and-tumble world just a throwback to macho condescension for the “fairer sex”? This issue of CJJ lines up articles that attempt to clear the clichés or prove that, with cover girls and more, perhaps “nobody does it better.”

Foreword

Fragile and yet it holds

CJJ6 departs from the format of the first five volumes of Cebu Journalism and Journalists.

It Suspends the photo-and-writeup listing and alots more space to articles about interesting facets of tne industry and its practitioners.

The lengthy pieces in CJJ6 are a revisit to the role of women in media, a review of Cebu Press Freedom weeks origin and progress, and a comparison of the work ernivironment in Cebu and other media communities.

CJJ, as chronicler, records how the local media has evolved as it copes with new technology and socal media amid the shiftS in readershp habits and choices.

Yet, old challenges remain. How Odd n this age that we still grapple with the threat of censorship and repression. A proposed ordinance would ban tabloids while two local legislatures wanted to summon a reporter and a columnist to explain their news and opinion before then. Guarantee of access to pudliC infomaton remains a legislative intent.

The local media’s projects and activities respond to the changing landscape and conditions. Cepu News Workers Foundation (Ceneof), Cebu Press Freedom Week (CPPW), Cebu Citizens-Fress Council, the medical aid fund (Cemmaf) and the legal arm (Cemla). Cebu NewCoop, MBF Cebu press Center, and CJJ Galery at Museo Sugbo: they celebrate partnership and unity and testify to a shared belief in freedom and accountability.

The unity can be fragile. Yet, through the years it has hled, which attests to a collectve wish and effort of the media community or for the bond to endure.

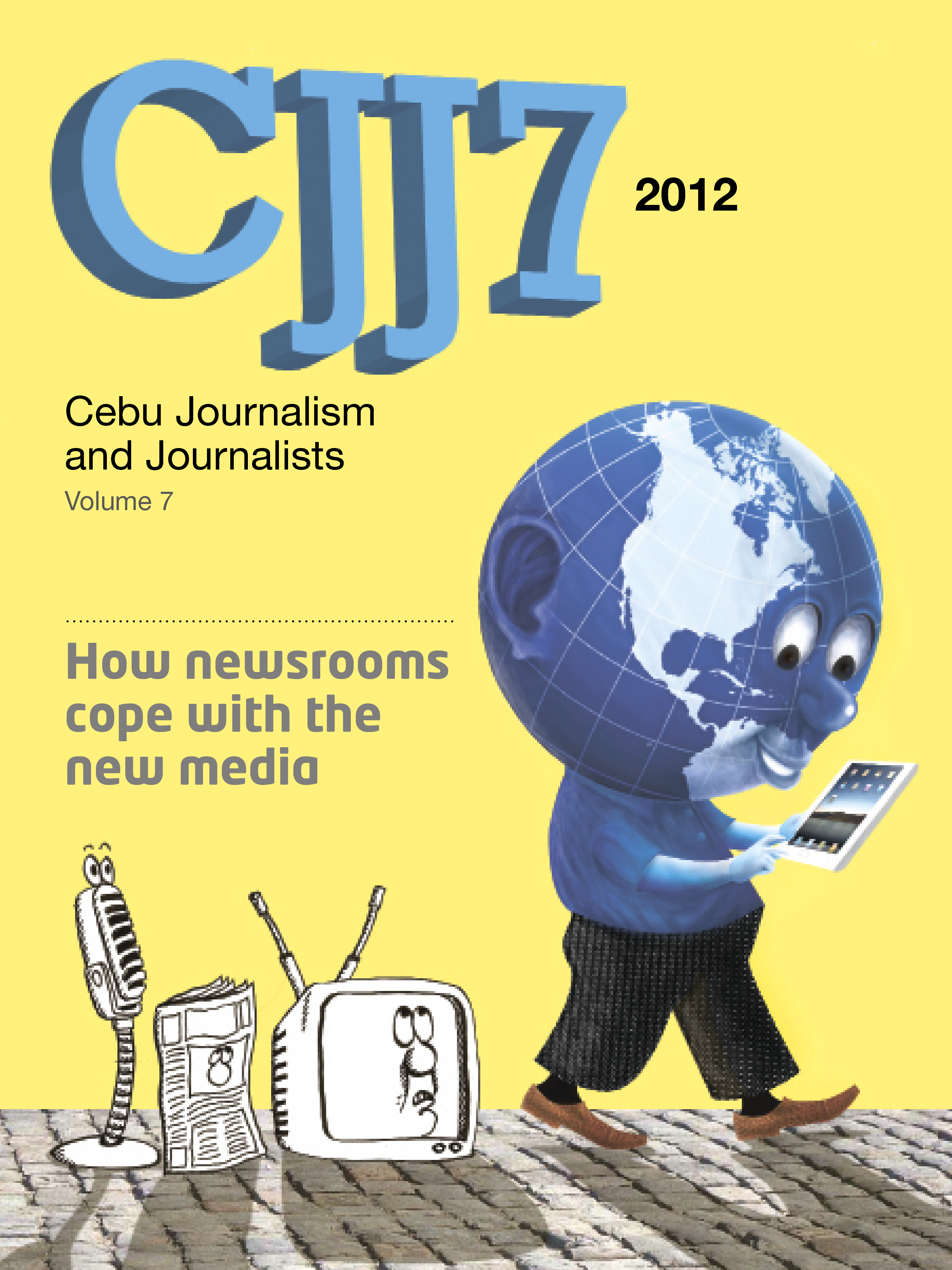

The cover

New tools, new press

How does convergence affect newsrooms? In bioconvergence, the merging of distinct technologies results in a new form, spawning new frames, new products and new practices.

Will the press be the same in Web 2.0? The seventh issue of Cebu Journalism & Journalists (CJJ7) has on the cover award-winning Josua S. Cabrera’s interpretation of this phenomenon.

Leading this year’s lineup is the main story on how mainstream media organizations are coping with the new media, particularly the internet, social media and mobile devices.

There are sidebars on live streaming, a writer straddling the old and the new portals, and editors’ views on content in the digital age. As with the earlier six issues, CJJ7 is released to coincide with Cebu’s celebration of the Cebu Press Freedom Week, which is held on the week where Sept. 21 falls. Filipinos will and should never forget what this day in 1972 means.

Though the digital tools seem to be just shiny new toys, these are latent with promise and threat. Then and now, what’s valuable remains the same: freedom, responsibility, commitment.

Foreword

What martial law instructs the press

Public relations executive pointed out at one of the cluster meetings held to prepare for Cebu press Freedom Week 2012 that its not only the 18th year of CPFW,it’s also martial law’s 40th year.

The talk led to how it could be reflected in few words and symbols. The result was the “1840” icon reproduced here.

Was it martial law that led to the annual celebration by Cebu’s print and broadcast media? Yes and No.

Yes because martial law, declared in 1972 and lifted in 1981 (although it wasn’t until 1986 that People power effectively ended it), haunted us even as it instructed that constant vigilance is crucial for the nation not to lose its freedom so easily and not to be entrapped in authoritarian for so long.

No, because there were incidents in Cebu, even after martial law, in which local tyrants, smaller versions of despots of 40 years ago, threatened or roughed up members of the working press or harassed them with lawsuits or legislative or executive action.

As reminder of the dark years, CPFW is held on the week that includes Sept. 21 when martial law began, among the seven days.

That is institutionalized in two resolutions of the Cebu City Council and the Cebu Provincial Board, which separately declared a Cebu Press Freedom Week every year in the cities and province of Cebu, and in a House of Representative resolution, which recognized and hailed the celebration.

Cebu media has set up as well mechanisms against infringement of press freedom, including a press council, a federation of beat journalists, and a news workers foundation and cooperative: all aimed to help promote a watchful, vigorous, yet responsible press.

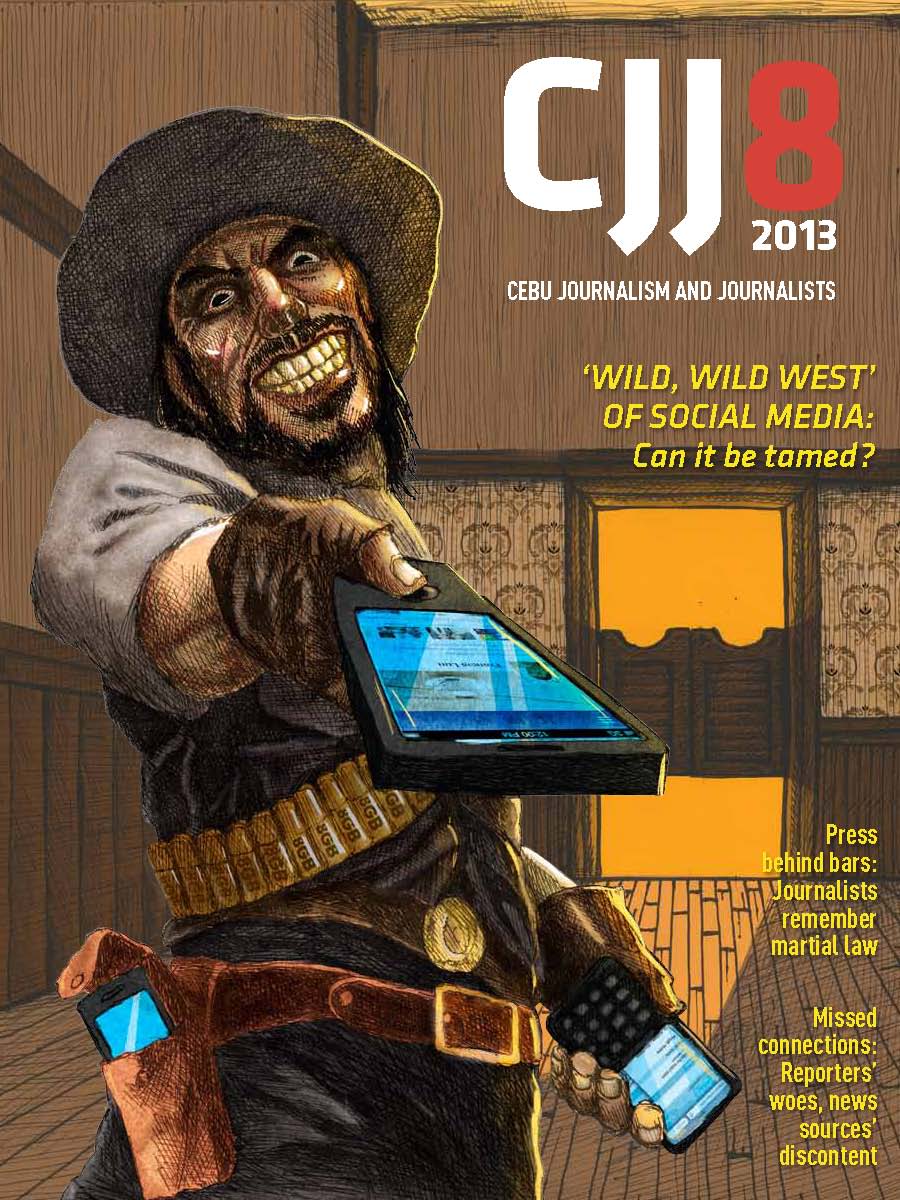

The cover

Before law and order

Comparing the social media to the “Wild West” underlines the impression of disorder and lawlessness, as well as of change and possibilities.

From the early 17th century to the 19th century, the western region of the United States drew immigrants from the old World, seeking a place to settle down, raise a family or reverse their fortune.

As metaphor and myth, the American frontier translates into revolution, freedom, release, expansion, disorder, violence, dissolution, subversion, change— associations not at all odd to apply to the social media, which change not just the way we communicate but also who we are.

From formerly being a commodity exchanged through an intermediary—known as the mass media—information is now generated, regenerated, altered, shared and reacted to by its actual users.

Making the messenger redundant is just the start of the revolution.

The cover illustrated by multi-awarded editorial cartoonist Josua Cabrera resonates with the insights of this issue’s cover story written by Gawad Plaridel awardee Pachico A. Seares that no revolution comes without cost.

Wild as it may be now, the social media hold out the possibility of transformation. As historian Frederick Jackson Turner theorized, the frontier, which stood for lawlessness and disorder, also was the process that transformed the people of the Old World into Americans, converted to the New World way of life: equality, individualism and democracy.

For now, we just have to ride this out.

Foreword

Who elected you?

A broadcast commentator once asked that in his remarks about a group of journalists who led the activities of the first Cebu Press Freedom Week celebration in 1994.

Austere as the program was then, persons were required to oversee it. It wasn’t like the parade, the forums and the fellowship would just take place by themselves. If even building a village chapel would need people to initiate, so would gathering Cebu’s journalists with conflicting interests and different temperaments. The “leaders” called themselves convenors, avoiding titles of public offices.

To ask convenors “who elected you?” was to question authority, when no power was asserted, and debase volunteerism, when no glory was sought.

One would think now that if the few persons who set up and toiled on the structure of Cebu Press Freedom Week were stymied and discouraged by the derisive assault, the annual celebration wouldn’t be as robust and significant as it has become in the last 19 years.

Unified media

Initialy an enteprise of a handful of journalists, Cebu Press Freedom Week is now infused with energy and zest from across the ranks of the industry, crossing boundaries of competition and rivalry and unifying practitioners, especially when the issue of press freedom is involved. More importantly, the annual celebration led to other efforts to improve journalists professionally and economically.

And in a way only few have realized, the question of “Who elected you” has influenced press activities in Cebu to be guided by collegial leadership, consensus-building, and agenda that benefit the media community.

During celebrations, the faces of convenors are blurred, almost unrecognizable. What the public sees is the face of a unified Cebu media, brought together by a shared purpose of improving its craft, the well-being of its practitioners, and its kinship with the community.

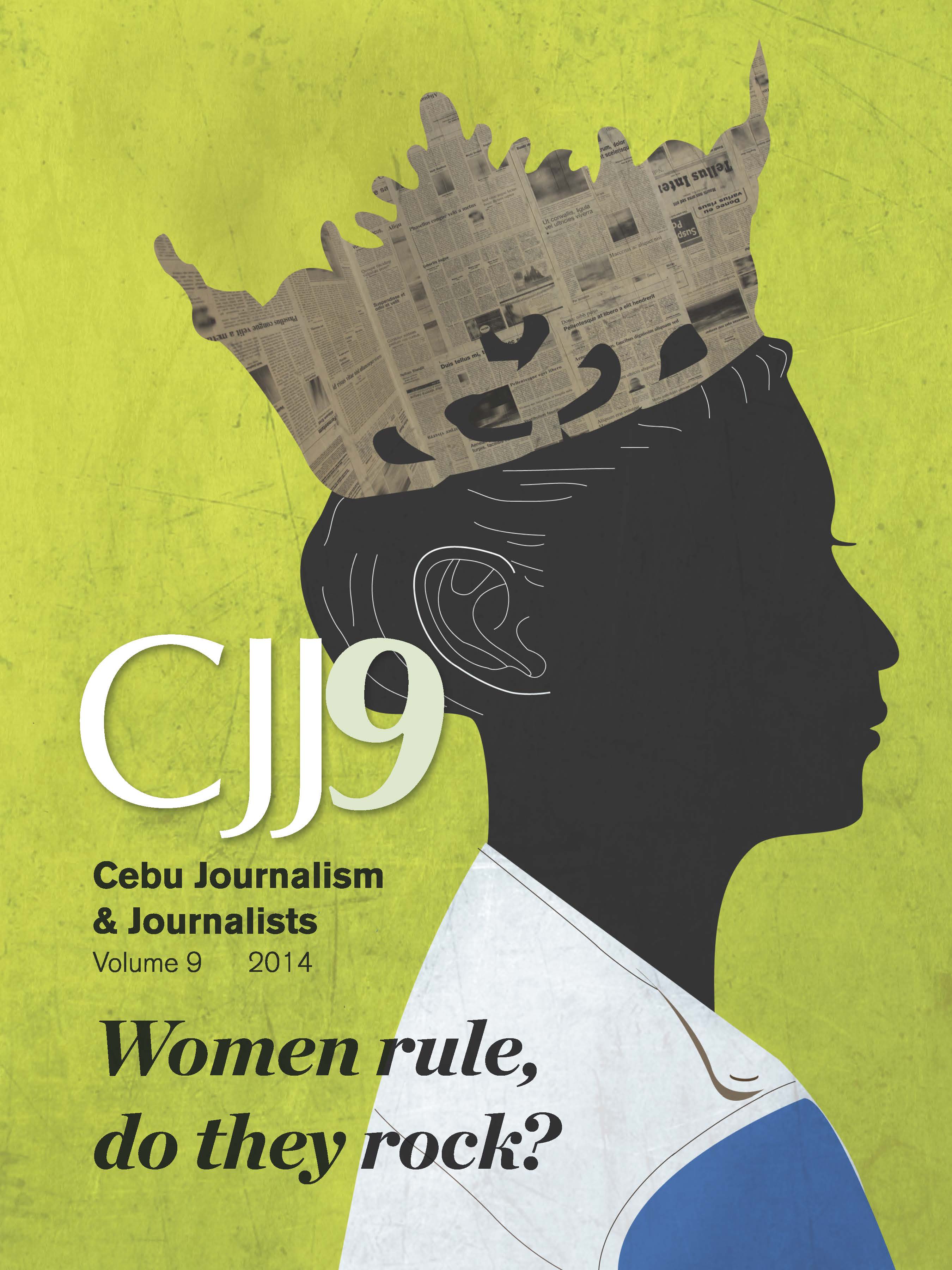

The cover

Breaking glass ceilings

Gender is a non-issue at work, claim some who believe that merit, not concessions to gender, boosts one’s ascent in the professional world.

Six women editors of Cebu, though, make one reexamine the gender angle.

In the ninth volume of Cebu Journalism & Journalists (CJJ9), he cover story by Rianne C. Tecson and cover illustration by Josua S. Cabrera focus on the editors who manage the newsrooms of five Cebu dailies, a major news bureau and a nationwide news agency.

In its tradition of documenting trends shaping Cebu media, CJJ9 records these editors’ management styles, response to industry challenges, specially the new media, and insights on breaking the glass ceiling in an industry that unselfconsciously coined the eyebrow-raising badges of yore, “news hounds” and “news hens.”

This issue also includes a feature by Gingging A. Campaña about three women who practice law and anchor television primetime news programs aired in Cebu. Do women rock? Or are they just lethal at lobbing the rock that breaks glass ceilings?

“Glass ceiling” refers to the “unseen, yet unbreachable barrier” that prevents women and other minorities from attaining top executive positions. It was coined by Gay Bryant in 1984, when he editor of Working Woman magazine was transferring to edit Family Circle.

Bryant’s cry that women were “getting stuck” in their climb up the corporate ladder remains resonant in 2014. Three decades after, last March 8, International Women’s Day, The Economist released a “glass-ceiling index” to show the “best and worst places to be a working woman” in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) club of rich countries.

Nordic countries topped the list for scoring nearly 80 in weighted average out of a scale of 100 in indicators on higher education, labor force participation, pay, child-care costs, maternity rights, business school applications, and representation in senior jobs.

At the bottom rung in The Economist glass-ceiling index were the Asian countries of Japan and South Korea. Yet, based on CJJ9’s coverage of women in journalism, the future looks bright in Cebu.

Foreword

Forgotten celebrations

It took several trips by Cherry Ann Lim and Erma Cuizon to archives in SunStar Central Newsroom library and Cebuano Studies Center at the University of San Carlos to confirm there were two celebrations of Cebu Press freedom Week (CPFW) that organizers had forgotten about: the first in September 1984 and the second in September 1988.

An account of the discovery, from news clips of two local newspapers in the eighties is on Page 26 in this year’s CJJ. With the article is the press week timeline, adjusted to include two pre-1994 CPFWs. That will place on record CPFW 2014 at 30 and 22: 30th year, 22nd celebration.

Reading the old files reminded us:

✓ there was a recurring complaint about Cebu media being in the business of recording and yet not recording facts about itself; and

✓ there was a bigger reason for holding a press freedom week than getting together at socials and forums.

Difficulty in tracking facts on the Press Week origin bears this out: befor CJJ, there was little effort to mesh threads in the fabric that is Cebu Journalism. Scant records about the industry and its practitioners even in the post-war era, going into the ’80s and ’90s, attest to the inadequacy.

This is not to say CJJ has solved the problem, but it has helped in storing in print and digital files a lot of information and ideas that may be useful to journalists now and historians in the future.

The old news clips also tell the major Cebu Press Week came into being-the then imminent threats on press freedom. Martial law, whose shackles were not removed until 1986 and whose vestiges remained scary for some time, made Cebu media embrace the imperative of an occasional jolting about vigilance. There were also incidents that proved repression could come even in broad light of democracy: 12 radio stations, 4 TV stations shut down, broadcaster detained and mauled; newsroom terrorized by armalite-wielding thugs; an ordinance seeking to outlaw tabloids, and similar assaults, open or veiled, violent or seductive.

Press week, observed in Cebu since 1984 serves each year as some kind of bell-pealing: basic freedoms could be lost by fragmented and eroded media.

Four words

Weakened media: lost freedoms.

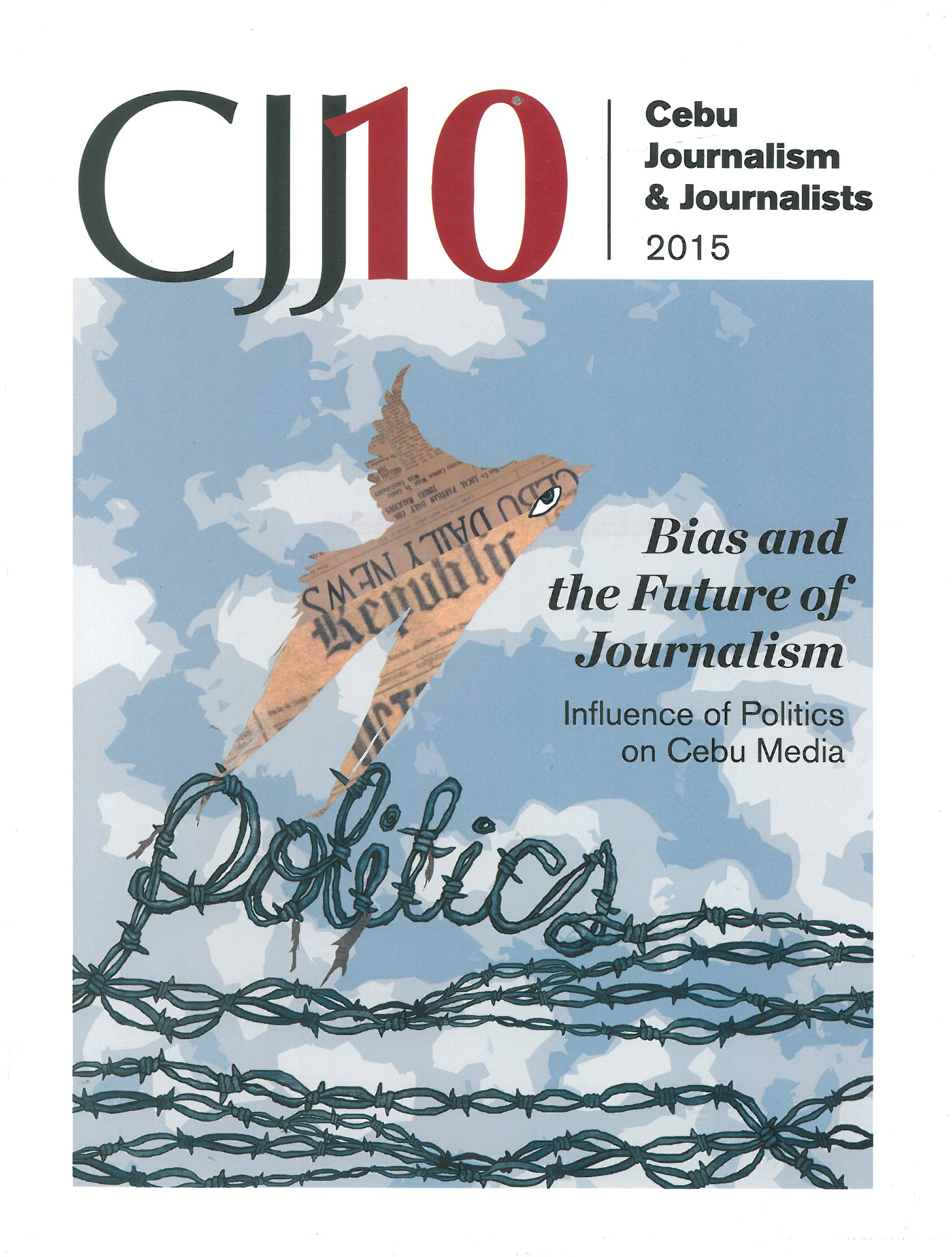

The cover

Sifting for deceptions

Trompe l’oeil is a technique in art that means in French to “deceive the eye.” A similar illusion is played by award-winning editorial cartoonist Josua S. Cabrera’s cover for the 10th edition of Cebu Journalism & Journalists (CJJ).

The two images, a bird and a barbed-wire wall, have become cultural semaphores. Signifying flight, escape and freedom, a bird represents the aspirations of true journalists—mainstream or alternative, tri-media or online—who desire to use access to information and freedom of expression to empower people so they can extricate themselves from inner or external repression.

Tracing the word “politics,” the fence of bristling lines snags a newsprint pinion and tail but fails to prevent the bird from taking wing.

Or does it? Long before media self-regulation, the early journalists wielded power as political propagandists. Even now, with professionalism as an industry norm and standard, there are journalists who don’t see any conflict in publicly covering the community and privately polishing the images of politicians and businessmen.

And though infamous as a game of power, politics traces its roots to the Greek word “politikos,” which refers to citizens, not politicians. Contemporary events in the country, as well as in the rest of the world, demonstrate how digital media has enabled citizens and civil society groups to wield people power to balance and counter the influence of political, economic and media elites.

Eminent historian and scholar Dr. Resil Mojares pens the article leading the lineup in CJJ10, centered on the themes: Bias and the future of journalism, influence of politics on Cebu media. With this issue, the CJJ team hopes that readers can be more adept at sieving deceptions from realities, whether in art or other realms.

Foreword

Past, present, future

A media issue, explored diligently enough, can tell something of the past show images of the present and provide glimpses of the future.

Three clusters of articles in CJJ10 exemplify that:

One, Resil B. Mojares’s article about bias and the future of Journalism cites the weakness of media, then as now, to fall for “staged events” directed by public persons and presented as hard news. Journalists bias is exploited by politicians who, even without buying the ink or the microphone, influence media for their personal purpose. Cebu medias shift from partisan to professional journalism is noted in a sidebar to the Mojares article.

Two, The efforts of a Cebu newspaper to circulate beyond its borders are revisited: SunStars thrust in key cities of the country through its media group. Problems and opportunities are examined amid developments in the industry.

Three, The new media: the ground being lost by mainstream media to the digital advances. Max T. Limpag, who straddles both sides of the divide, reports.

Even on features presented in single articles, there’s the flux of what had gone before, what’s going on and what to expect ahead, Such as the pieces on the murder of Cebu journalists, lessons learned from coverage of past elections, hopes tor the MBF Cebu Press Center, two styles in writing opinion columns, and the like: snapshots of the past, tales in the newroom and images of journalists.

Which is what CJJ has aimed to do in chronicling its subjects of interests.

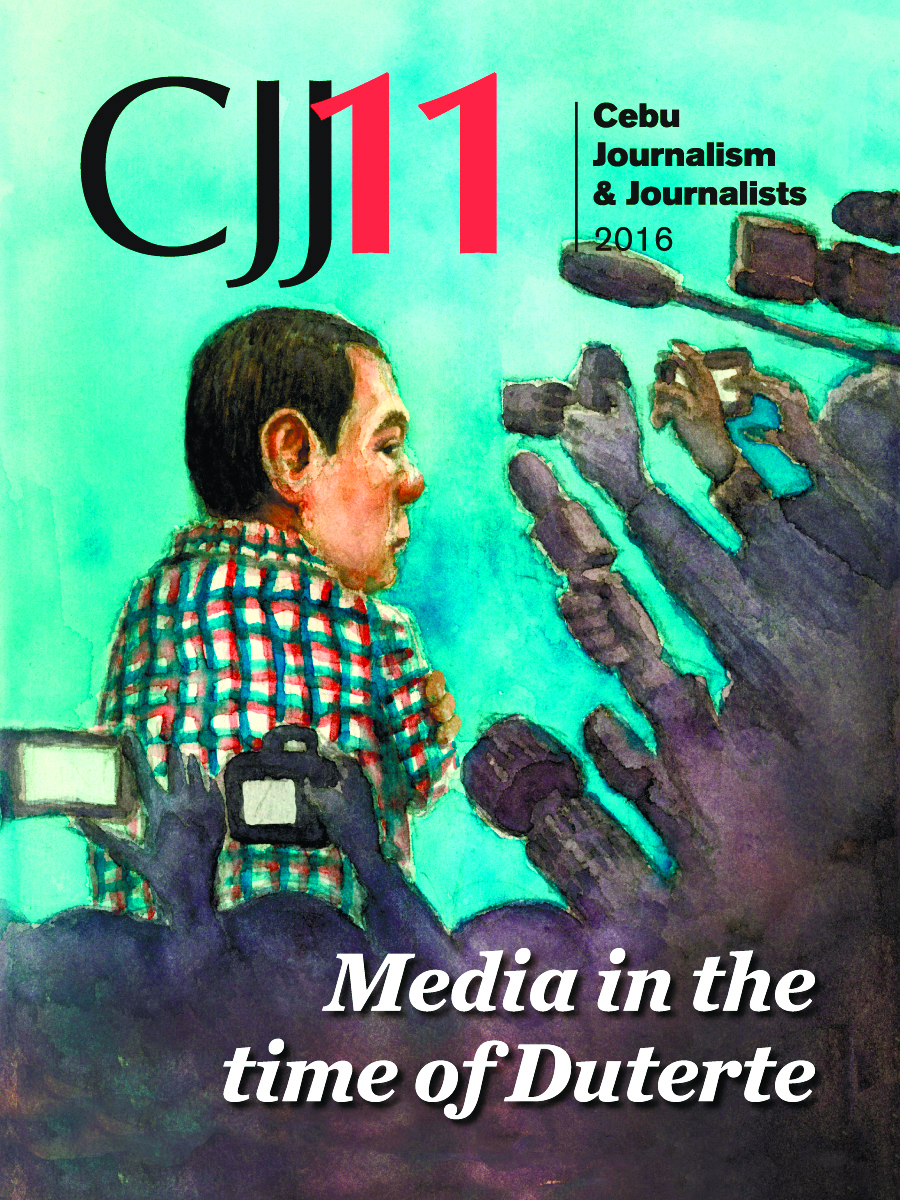

The cover

Four words

Free press, accountable press

Close encounters

Dominating the year and this year’s issue of the Cebu Journalism & Journalists is, hands down, President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, sketched on the cover by award-winning editorial cartoonist Josua S. Cabrera.

He is the first president to come from Mindanao. Of Visayan descent, President Duterte commands not just the attention of the regional and the national media, traditional journalists and online citizen-journalists.

Running on a platform of populism, President Duterte’s landslide victory was not just a result of social media handling but unprecedented engagement with Netizens, many of whom became his unofficial spokespersons and vanguards, taking on anyone perceived to criticize the man who courted controversy with every public curse and politically incorrect joke or comment.

His presidency is no less colorful than his candidacy. When he said that corrupt journalists deserve their deaths, national and international media condemned his insensitivity to media killings and the culture of impunity.

Retaliating to a call for a media boycott, President Duterte bans or limits media companies’ access to him, permitting only government media.

And yet, just 25 days from his inauguration, President Duterte signed an executive order implementing freedom of information (FOI) in the executive branch. Since Rep. Raul Roco filed the first FOI bill in 1987, various FOI bills have been filed in successive Congresses in the next 28 years, without yielding the FOI Law.

So what is the media supposed to make of the maverick president? Veteran journalists from Mindanao Stella Estremera and Froilan Gallardo tackle President Duterte and his hot/cold relationship with the press.

Other articles explore Cebu local executives’ responses to the demand for greater transparency. Storytelling in the age of social media is also probed in this issue.

Who was it who said these striking lines? “I abhor secrecy and instead advocate transparency in all government contracts, projects and business transactions.” “You mind your work, and I will mind mine.” The country’s 16th president.

To borrow another classic line from sci-fi, “The truth is out there.”

Foreword

Just tougher but same task: getting it right

President Duterte is not an ordinary news source, Cagayan de Oro senior reporter Froilan Gallardo notes on media’s preoccupation to analyze the president. True, Duterte steers the ship of state, which can sail the horizon or ram a huge rock.

Since he mounted the national stage-tirst as reluctant nominee, then as shrewd candidate-he has befuddled journalists here and abroad.

Reporters covering him and editors directing from newsrooms, mostly of Manila-based news outfits, have been at times confused and annoyed. They can’t figure out what he wants to do. Does he have limits on his goals? Media isn’t sure because he doesn’t always say what he means, as candidate and election winner and now as sitting president who’s making many people, here and abroad, sit on edge.

Aside from occasional curses and insults, Duterte exaggerates, tells anecdotes and jokes, flip-flops. In short banter or lenghty monologue, communication may be garbled. Davao-based journalists and Duterte has advised:get what he means.

It’s not actually a new task, Every journalist is faced with that constant challenge in his job: the reporter who sifts through facts, the editor who gathers meaning from interlocking events, the opinion maker who must weighin with his view. Duterte is just making the work a lot harder.

Media has been cautioned: if you don’t get it, ask again. With his suspension of press-cons, that can’t be done directly. But he has publicists and spokespersons, Cabinet heads and undersecrataries who can explain, if they can, with filter and all.

Less than 100 days in the Duterte era, the president signed a Freedom of information executive order, making previous presidents look like slick promisors. And an improved media policy is evolving, which may include the administration giving its messages plain and straight to avoid confusion and misinterpretation.

It’s very much part of CJJ’s mandate, in its modest chronicling of journalism and journalists, to help make sense of what our leaders think of media and how their decision affect its coverage on governance. It could mean the life of free speech itself.

Four words

Ask the hard questions

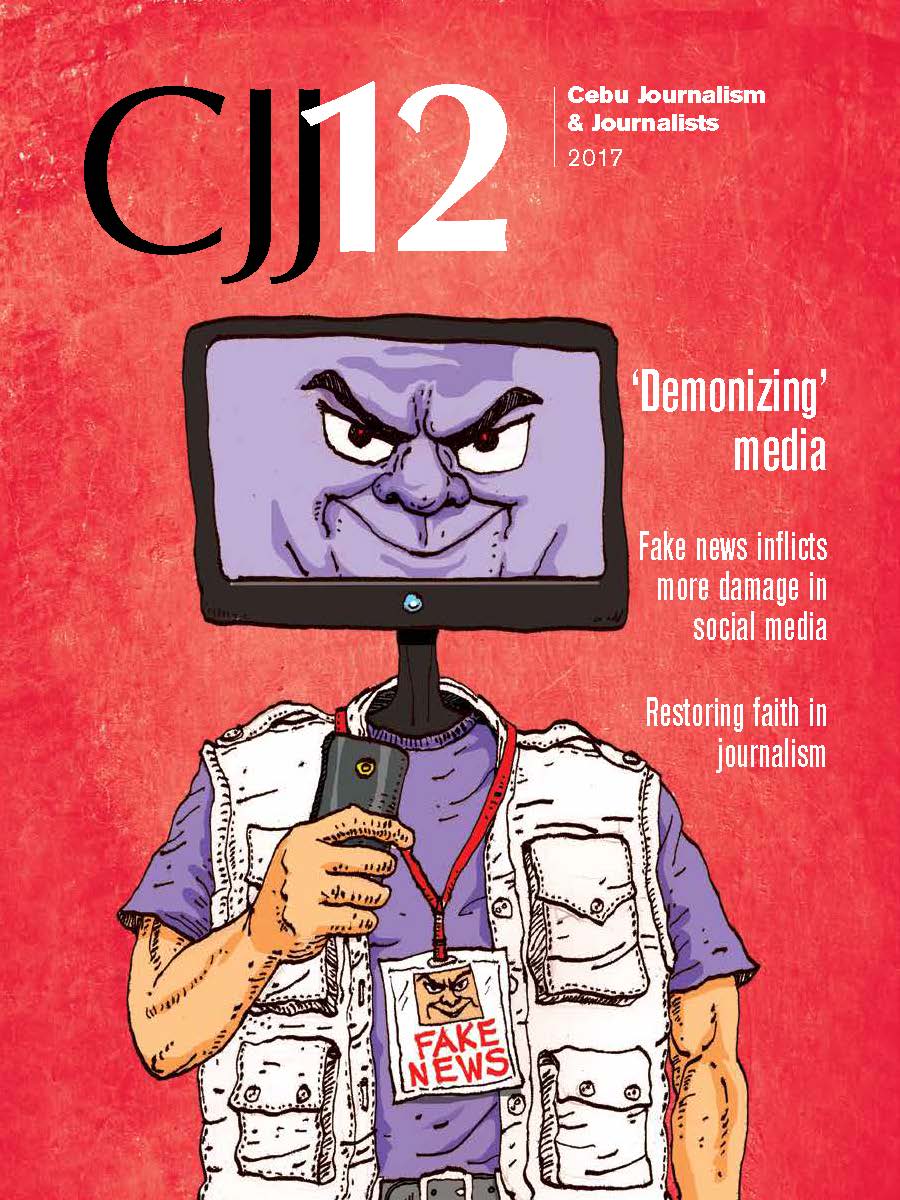

The cover

Wanted: G.I.s (Genuine Items)

There’s no gray scale to redeem fakes. The tamest synonym for fake is perhaps simulacrum, which means an imitation or substitute.

Yet, simulacrum still implies something unsatisfactory, the kindest putdown for fake.

Applied to news and journalism, fake stirs up a cauldron of controversies.

As illustrated by multiple award-winning Josua Cabrera, art department chief of SunStar Cebu, fake news poisons audiences’ minds with half-truths, unsubstantiated information, and maliciously altered facts.

Trolls and bots are not the worst creatures to crawl out of fake news. It’s the stigma insidiously associating fake news with journalism.

If you don’t like the news, blame fake news. If the news does not fit your biases, blame fake news. If you prefer to borrow opinions and your leader blames the @#%! media for everything he has not achieved, blame fake news.

The 2017 issue of Cebu Journalism and Journalists wants to cut the vicious cycle and remind every citizen, every stakeholder of these four essential points, excerpted from the “Truth Text” published by The New York Times:

“The truth is under attack.

The truth is worth defending.

The truth requires taking a stance.

The truth is more important now than ever.”

Foreword

In the time of fakery, which media to trust

Attempts to repress media are usually foiled by defense of free speech and free press. Yet how can free speech be justified if media cannot be held accountable for abuse or excess?

Mainstream media has long accepted the limits on free speech and free press.

Libel laws provide for both criminal and civil liability. Punishment for contempt curbs disrespect to the courts and legislative bodies lawfuly exercising the power of inquiry Industry and individual in-house rules on ethics restrain offensive behavior that falls short of a crime.

In sum, media is regulated not just by the state. Practitioners submit to scrutiny by their respective media outlets, their peers and their public. Yes, their readership or audience, which, as consumers, may stop reading or watching the media they can no longer trust.

The setup has worked for mainstream media, print and broadcast, but maybe not for online media, particularty the sectors that have no rules and no gatekeepers that curb misconduct.

Fingers point to social media, whose plattorm managers are still scrambling how to keep toxic messages of anger and hate away from the conversation. Mainstream media police their own ranks. Social media managers are struggling, almost helpless or unwilling to supply filters in the internet that, by its concept, is totally free but, as essential Civility sinks in, should not be.

Immediacy of access and posting, And anonymity. Those give the edge in internet communication but they are also the bane. The voices are quick and bold but because they are not identified, they ignore restraints that keep the regular media careful with the facts in the news and the logic in their commentaries. Spewing out and circulating bogus information and unleashing diatribe recklessly are usually not impeded in the internet. Masked, faceless, or using false names, authors can peddle ignorance, often aimed to promote hate and violence, at times for profit. The sense of impunity among the offenders is inevitable. In this era of fakery, mainstream media must protect and nurture its greatest strength: its capacity, skill and shared value in getting at the truth. It is vulnerable to mistakes but it has great respect for the facts.

Four words

Trad-media holds itself accountable.