Gov’t. will give legal aid to journalists but they have to qualify as indigent and apply. Not as tough as you may think.

Surviving libel, other complaints

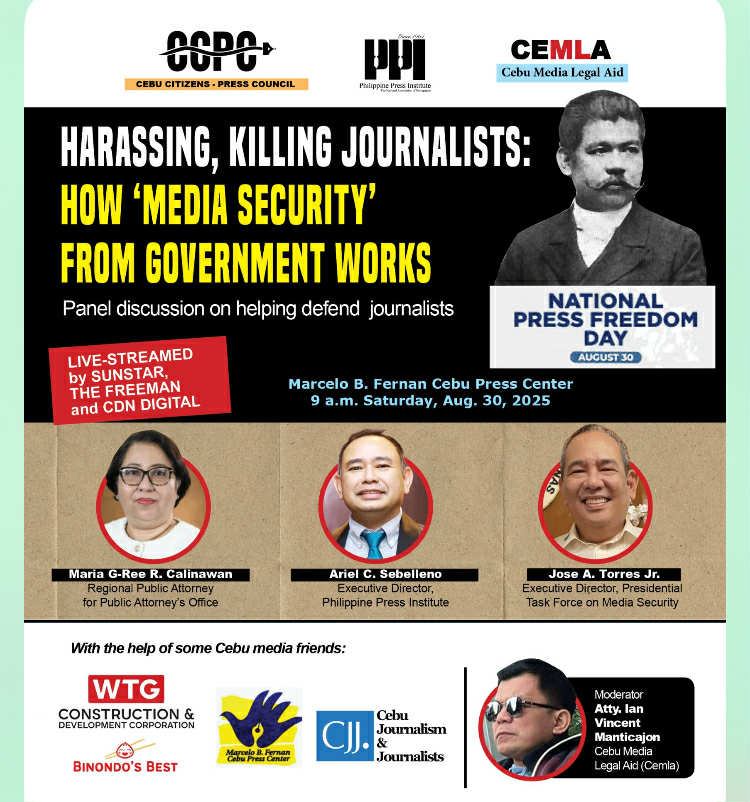

Announcement of the Aug. 20, 2025 panel discussion conducted by CCPC and Cemla.

Gov’t. will give legal aid to journalists but they have to qualify as indigent and apply. Not as tough as you may think.

Aug. 30, 2025 forum raises anew the problem of public demand for ethical behaviour from economically-distressed news media

IAN VINCENT MANTICAJON

Sept. 26, 2025

[From his report as moderator of the 2025 National Press Freedom Day panel discussion]

The 2025 National Press Freedom Day panel discussion held last Aug. 30, 2025 highlighted, if not dug up fresh for the Cebu public, sobering requirements for a journalist to get legal assistance from the Public Attorney’s Office under its agreement with the Presidential Task Force on Media Security (PTFoMS).

More interesting are these:

[] The aid-seeker must be “indigent” with less than P22,000 a month and has no income-earning properties. If the threshold is tough to cross, one can still get PAO help by showing unpaid debts, which will bring it down to the required income.

[] The protection appears not to cover the news outlet or the journalist’s employer even if the latter qualifies as an indigent, given current economic woes of media outlets. The MOA must assume that employers and news outfits have the money to hire a lawyer for the company, if not for their journalist who is sued. The assistance also does not apply to criminal cases where the journalist is the complainant.

[] PAO will defend the qualified journalist even if the person suing him or her is government personnel or office, “as long as the case is not intended merely to harass the government side.”

The report by Atty. Ian Vincent Manticajon sorts out the PAO-PTFoMS rules — including not giving money for the journalist’s bail –on government support to media. The discussion, unavoidably, brought up once again the media industry’s plight: coping with the economic distress amid demand from the public and the industry’s commitment about ethical behaviour. PAS

Main resource speakers in person: (top, center) PPI’s Ariel Sebellino and PAO’s Atty. Maria G-Ree Calinawan,with moderator Ian Vincent Manticajon, a lawyer-columnist. Jose Torre Jr., PTFoMS chief, sent a video message. The forum was held at the MBF Cebu Press Center in Lahug, Cebu City.

THE forum on journalists’ safety was held at the Marcelo B. Fernan Cebu Press Center on National Press Freedom Day, Aug. 30, 2025 commemorating Marcelo H. del Pilar, hailed as the father of Philippine journalism.

Organizers Cebu Citizens-Press Council (CCPC) and Cebu Media Legal Aid (Cemla) underscored the historical continuity between Del Pilar’s sacrifices in exile and the present-day struggles of Filipino journalists who continue to face harassment, threats, and even death.

Cebu, in particular, has recorded since 1961 at least 15 violent assaults against news media workers, resulting in 11 killed and four wounded, many of which have been unsolved, shelved as cold cases, or failed in prosecution.

RELATED: Attacks on Media Workers: The CJJ List, updated 2024

The forum brought together, moderated by Atty. Ian Vincent Manticajon, representatives from government agencies, press organizations, and working journalists.

The stated objectives were threefold:

[] Clarify the scope and limits of assistance from agencies such as the Presidential Task Force on Media Security (PTFoMS) and the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO).

[] Promote informed decision-making among journalists on when and how to engage with these agencies.

[] Reaffirm press freedom and independence while strengthening protection mechanisms.

Legal aid from government

Jose Torres Jr., executive director of Presidential Task Force on Media Security, reaffirmed in a video message that the Government is committed to journalists’ safety.

While generally declarative, his remarks framed PTFoMS as a mechanism to respond to killings, threats, and harassment in the media industry.

No matter what you think of PAO services, we are always available to help you.”

Maria G-Ree Calinawan, PAO’s regional public attorney.

Atty. Calinawan of PAO Region VII explained terms of the newly signed memorandum agreement (MOA) between PAO and PTFoMS. Under this agreement, PAO will provide:

[] Free legal assistance to journalists —professional or campus, no distinction — in criminal, civil or labor cases provided they are work-related.

[] Services such as affidavit preparation, documentation, notarization, and representation in court.

Victim’s income, properties

PAO cited requirements and limits that qualify the assistance:

[] Journalists must request for the help. PAO cannot intervene on its own.

[] Bail cannot be provided, though motions for reduced bail or release on recognizance may be filed.

[] Aid is subject to proof of indigency, with income threshold applied depending on locality — PhP22,000 net income per month or lower for those living in Cebu City and other highly urbanized cities.

PAO also clarified that having properties does not automatically bar a journalist from qualifying as indigent, as long as the properties are not income-generating.

Outstanding loans or debts can be factored in when assessing income.

This means that even if a journalist’s gross monthly income seems to exceed the threshold, their net disposable income (after deducting loan payments and obligations) may still qualify the journalist for legal assistance.

Along with the qualifiers, there’s a ban on assistance to a journalist who files a criminal complaint against another person. Atty. Calinawan said PAO’s assistance covers situations “where a journalist is the accused or is defending against a complaint, such as libel, cyberlibel…”

It’s mandate is defense of “indigent” journalists, not prosecution.

Ariel Sebellino, PPI executive director

There is no real press freedom when the journalist’s stomach is empty.”

What community

media face

Ariel Sebellino, executive director of the Philippine Press Institute (PPI), contextualized the broader challenges confronting the media. He described the ongoing existential crisis of journalism:

[] Community newspapers and regional outlets, already fragile, were further weakened by the pandemic and the loss of advertising revenues to big tech platforms.

[] Journalists face not only physical threats but also economic precarity, summarized in the line: “There is no real press freedom when the journalist’s stomach is empty.”

Sebellino emphasized that press freedom is “not granted by the state but secured through generations of struggle.” He called for “plural and complementary efforts” among government, press councils, and NGOs, while reminding media employers of their responsibility to provide preventive safety measures such as insurance, protective gear, and security protocols.

The heart of the forum lay in the testimonies of working journalists, whose personal accounts underscored the risks and systemic failures they face.

Rico Osmena related how he was shot and wounded on Dec. 16, 2021. No. 4 in CJJ list of journalist victims of shooting who survived. Among the four survivors, one was later shot again and killed; another died from an illness.

RELATED: [] CJJ list of journalists shot and killed and journalists shot and wounded

[] Seares in SunStar, Jan. 14, 2022: “Broadcaster Rico Osmena who survived Dec. 16, 2021 gun attack still in pain…”

Journalists testify: Rico Osmeña…

Rico Osmeña, veteran print and broadcast journalist, survived a 2021 gun ambush after exposing agricultural smuggling and corruption at the Cebu ports. He recalled facing 13 libel cases and a smear campaign, yet continuing investigative work. He lamented despite initial investigations by PTFOMS and law enforcement, his case stagnated at the CIDG, allegedly due to the mastermind’s wealth and political connections.

Osmena said he continues to suffer lasting physical pain from his injuries. He proposed establishing an emergency trust fund for journalists, recognizing the inadequacy of government bureaucracy in times of crisis.

… and Ormoc City’s Josie Serseña

Josie Serseña (right) — at the forum, with CCPC deputy director Marit Stinus-Cabugon — is a news correspondent based in Ormoc City. She told a Cebu audience how she was made to strip naked after her arrest on July 5, 2024 for ignoring a court summons she alleged she didn’t receive.

Josie Serseña, correspondent of Eastern Visayas Mail in Ormoc City, narrated her traumatic experience of being arrested on a bench warrant arising from allegedly ignoring a summons she never received. She had been required to serve as a witness in a drug buy-bust case she was covering, a practice long opposed by press groups for endangering reporters.

Despite no prior summons, she was booked and detained as if she were an accused. She stressed the irony of being punished while fulfilling her civic duty and calling for reforms to prevent miscarriage of justice. PFToMS later assisted her case, but she highlighted the need for better coordination and systemic safeguards.

Both testimonies exposed the dangers posed not only by powerful figures hostile to journalists but also by the justice system itself, which sometimes inadvertently treats reporters like criminal suspects.

Media ethics, disinformation,

public’s role

The forum also addressed the ethical responsibilities of journalists in a polarized media environment. Questions from students raised concerns about celebrity journalists accused of compromising ethics by accepting questionable payments.

Panelists responded that:

[] Media ethics must be openly discussed and treated as central to the profession.

[] Journalistic credibility rests not only on skill but on adherence to ethical standards and avoidance of conflicts of interest.

[] Investigative and collaborative reporting must replace shallow “he-said-she-said” coverage, especially in uncovering corruption and rights abuses.

[] In the absence of strong institutional accountability, public scrutiny through social media has emerged as a form of pressure, though it must be harnessed responsibly.

The discussion emphasized that ethics is both a personal commitment and an institutional obligation, guided ultimately by the “murmurings of conscience.”

Key themes, takeaways

In the forum, some key themes and takeaways emerged.

There’s the continuing impunity in harassment and violence against journalists.

Assaults on media workers often remain unsolved or fail in prosecuting offenders while perpetrators, with wealth and influence, evade accountability.

Another sad fact is that while PAO and PFToMS offer important legal and security support, their roles remain largely reactive and limited by bureaucracy. Real protection often depends on solidarity from press councils, employers, and civil society, rather than government agencies alone.

Also, journalists struggling to sustain livelihoods cannot fully exercise independent watchdog roles. But upholding credibility through ethical journalism is the key to resisting both external threats and internal compromises.

ATTY. IAN VINCENT CAVADA MANTICAJON is a senior lecturer at the University of the Philippines Cebu, where he teaches communication, media law, and ethics. He also serves as a Human Rights Law professor at the University of Cebu School of Law. In addition to his academic roles, he is a practicing lawyer engaged in the areas of family law, criminal law, property law, and human rights law.

Atty. Manticajon holds a law degree from the University of San Carlos and a Master’s in Design from Shu-Te University in Taiwan, where he focused on sustainable and user-centered design. His diverse educational background combines legal expertise with a practical approach to sustainable community projects.

In his legal work, he is actively involved in civic and advocacy groups, including the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG), National Union of People’s Lawyers (NUPL), and Cebu Media Legal Aid (CEMLA).

In 2014, he received the Tatak UP Award from the UP Alumni Association Cebu Chapter for his contributions to legal education and community empowerment. He is also a columnist for The Freeman in Cebu. Atty. Ian Vincent is married to Atty. Arrah Camillia Q. Manticajon and hails from the town of Catmon, Cebu. He currently resides in Banilad, Mandaue City.