Museo Sugbo, rescued from closure and demise, returns as Cebu’s premiere heritage site: ‘Window to Cebu’s soul.’ ‘Repository’ of Cebuano culture and history.

Media facilities, projects, doings

Museo Sugbo, rescued from closure and demise, returns as Cebu’s premiere heritage site: ‘Window to Cebu’s soul.’ ‘Repository’of Cebuano culture and history.

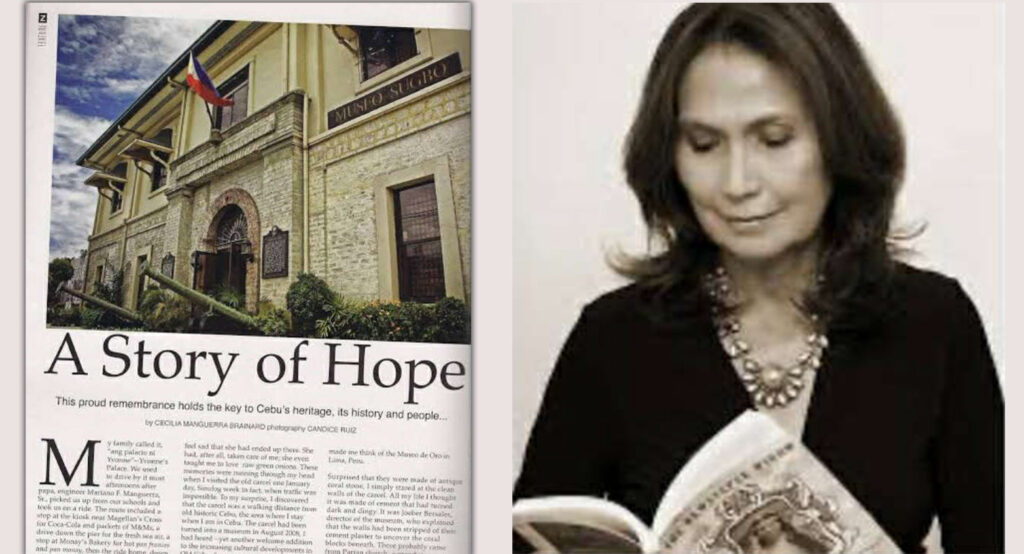

◾ The museum — housed in the former Carcel de Cebu, the provincial jail that was built starting 1871 at its location along M.J. Cuenco Ave., Tejero, Cebu City — cannot have a more “significant and apt setting” for its content and display. Which seemed to be the consensus in 2008 when Museo Sugbo was inaugurated and in 2025 when it was reopened.

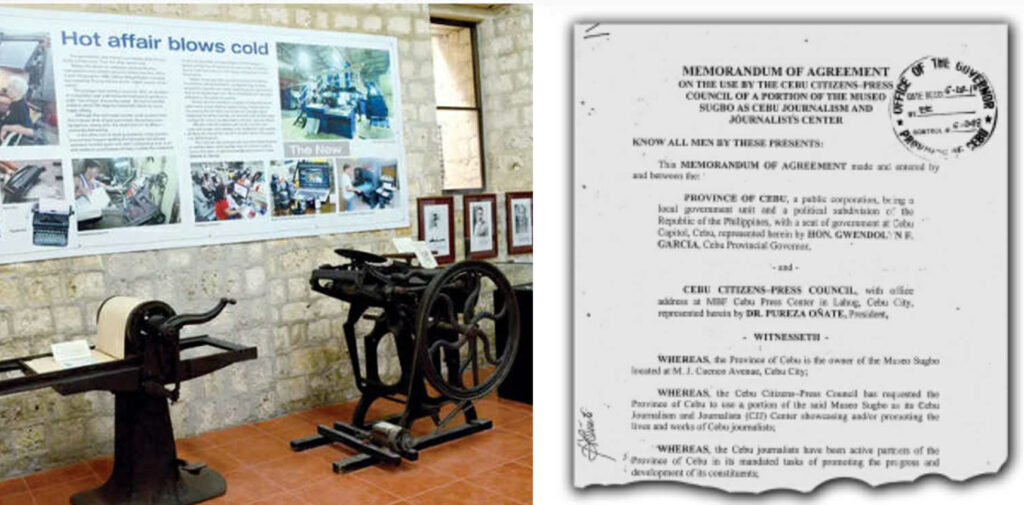

◾ Disclosure: Cebu Citizens-Press Council (CCPC) has joined the cluster of exhibits in Museo Sugbo: CJJ Gallery, aka Cebu Media Gallery, under a contract with then governor Garcia, ratified by the Provincial Board.

Gov. Pam Baricuatro, in her invitation to the reopening of Museo Sugbo on Aug. 28, 2025 — after its closure for almost two years by the administration she succeeded — called Museo Sugbo “a window to Cebu’s soul” and “a gateway’ to the past” that, the new governor said, inspire our people and inform the world about our history.

Then governor Gwen Garcia, on Aug. 13, 2008 when Museo Sugbo was inaugurated, said she “repurposed” the the provincial jail into a museum because she wanted to turn the historic site into a repository of Cebu’s heritage and culture, that will feature galleries with artifacts, documents, and exhibits that highlight Cebu’s history.”

In 2010, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, award-winning Fil- Amercan author-editor of two novels and 20 other books, wrote after a visit to the Museo: “The documentation of Cebuano culture in Museo Sugbo validates what I had always known, what always had been there, but which had been ignored for so long.”

The article about Museo Sugbo was reproduced in the Jan. 11, 2013 blog “Travels (and More) with Cecilia Brainard.” The review was first published in hard-copy magazine “Zee Lifestyle” of June 2010. Writer Brainard, born in Cebu in 1947 to Mariano Flores Manguerra and Concepcion Cuenco Manguerra, grew up in Cebu City. She attended St. Theresa’s College Cebu and Manila, got her B.A. in Communications degree from Maryknoll College Manila, and studied film-making at UCLA in the U.S.

The three influential persons offer compellingly strong arguments:

◾ Baricuatro’s 2025 statement on why the Museo should reopen after being shut down for more than a year;

◾ Garcia’s 2008 declaration of purpose for the museum and the “carcel”; and

◾ Brainard’s 2010 assessment that the Museo has “documented” and “validated” Cebu’s claim to history and culture.

Which unavoidably leads to the question why the Museo was closed down (for one year and nine months, counted from Dec. 1, 2023). Was there “a change of heart” by the decision-makers, a new passion, a different pursuit?

CJJ asked journalist Iris Hazel Mascardo of The Freeman to find out from Jose Eleazar “Jobers” R. Bersales, Capitol consultant on heritage and culture, the workhorse that turned Garcia’s concept and project into reality — and, now that Museo Sugbo is reopened, to keep it open, active and vibrant.

Destiny or an imperative, Jobers Bersales has shifted from the tough task of setting up the Museo to the tougher work of prolonging its life despite the vagaries of change in administrations and leaders’ priorities.

Mascardo ‘s article produces some insight into the phases that Museo Sugbo has gone through. —  Pachico A. Seares

Pachico A. Seares

The marker, in Cebuano-Bisaya, about the former-jail-now-a-museum. Maybe it should’ve a ‘footnote’: the crucial information that for one year and nine months it had been closed and almost died.

The why: Mainly about money or the lack of ready cash. Jobers Bersales talks of factors that led to Museo shutdown — and revised priorities that resulted in its reopening. The how: what must be done to keep a heritage site going.

IRIS HAZEL MASCARDO

Jobers Bersales — the Capitol consultant who did the huge work of researching and preparing for then governor Gwen Garcia’s conversion of the provincial jail into a museum in 2008 — confirmed the reason for Museo Sugbo’s closure 15 years later, in December 2023. It had become “too costly” to operate and revenue from ticket sales and event bookings could not cover basic expenses.

Bersales said operational cost was ₱5 million per year while revenue reached only ₱1.8 million to ₱2 million. It was not profitable, if it were a business enterprise. Not enough for its upkeep, if it were an activity on which the Province shouldn’t or didn’t want to spend money.

Jobers Bersales, Capitol consultant on heritage and culture, designed Museo Sugbo.

Jobers recalled — what seemed “just like yesterday” — how he learned that Museo Sugbo, which was and is “ close to his heart,” was already shuttered.

It was an ordinary day for a professor like him, teaching in Osaka, Japan, when his phone rang. It was a call from his hometown— from the Tourism Office in Cebu City, Philippines— telling him Museo Sugbo had been closed. He had not been informed about the plan or its implementation.

The Museo shutdown was done following an assessment, he was told, by then Cebu governor Governor Gwendolyn Garcia.

Not enough for upkeep

Maintenance of the museum was “high” and Capitol at the time must have been hard up on cash flow. When it had to cut costs, its priorities — which allocates huge amounts for activities like Suroy sa Sugbo (P50 million) and “Pasigarbo sa Sugbo” (P200 million) — apparently didn’t include the less visible, “under- trafficked” Museo sa Sugbo.

One speculation then in the gossip mill in Cebu — where like most other places theories are examined and passed around before they’re discarded — was that the prime real estate would be used in a joint venture or partnership with some private business group. That was a plausible thought then, given the entrepreneurial activism of then guv Gwen.

Museum is ‘a service’

About Museo Sugbo earning profit, Bersales, like most other people who value Cebu heritage and culture, said: “No museum is ever profitable. “Everybody in the world (knows) there is no such thing as museum that is a business enterprise,” said Bersales. “A museum is a service, it’s there to inspire people, it’s not there to make money,” he added.

At most, projects like the Museo can seek to reduce cost by seeking revenue related to its operation and, in addition, donation from the community or subsidy from the government.

Not in Cebu ‘to defend it’

A disheartened Bersales said that upon receiving the unexpected call from Cebu he thought he had missed opportunity to defend the museum’s value. “I was not there to defend it.” Saddened as he was, he said he understood that the governor must be looking at the situation differently.

Bersales believed that the opening of the National Museum may have contributed to the decision. Capitol may have thought that with the National Museum already operating in Cebu, Museo Sugbo has become redundant. To him though, the two museums are “very different institutions.”

When he returned to the Philippines three months later, Bersales reached out to the National Archives to take over Museo Sugbo, including its restoration and renovation. However, the National Archives was unable to secure national funding to rent and manage the institution.

Option on National Archives

“I was scrambling, I was looking for (options), if the province is no longer interested in Museo Sugbo, we might as well rent it out to a national cultural agency,” said Bersales. “But the National Archives took quite a long time, kay they have to justify that they have to rent out the Museo Sugbo,” he added.

Despite initial negotiations, Bersales said the plan didn’t push through, as no funding was available from the national government in 2024 and 2025. When the closure was announced, his immediate concern was for the objects inside the museum, most of which were not provincial property but were on loan from private collectors.

Repairs, security

During that time, all personnel assigned to the museum, including eight security guards, were removed and reassigned to other offices. Bersales yet managed to retain one curator to oversee the removal and safekeeping of the objects, which “Governor Gwen did allow.” The curator remained “to watch over the (objects).. even if she closed this, she provided security from the Civil Security Unit.”

Right after the closure, Bersales said there were multiple attempts to repair parts of the structure damaged by an earthquake. Even then, they had been receiving calls and visitors at the gates asking if Museo Sugbo was open for tourist visits. “While the governor closed the museum, she actually allowed its maintenance, naa pay mga tawo nabilin,” said Bersales.

‘Home to Cebuano culture’

Museo Sugbo, according to Bersales, was among the top museums during its operation. Its walls were “vibrant” and often enticed students to visit. He recalled that it housed a historic collection of artworks, including pieces from his personal archaeological excavations conducted under the National Museum.

To Bersales, the museum has become a home to Cebuano and Filipino culture. “It has complemented the National Museum and served as its Cebuano counterpart.”

“We don’t compete with National Museum,” said Bersales. “For the Cebuano people, Museo Sugbo is a place to learn and unravel history.” Bersales said Museo Sugbo is “a good starting point to understand Cebu better.” The public can see artifacts ranging from the pre-colonial period to World War II.

Gwen’s change of heart

He emphasized that Cebu’s World War II history could only be found at Museo Sugbo. Bersales shared that he knew the museum by heart—after all, he designed it.

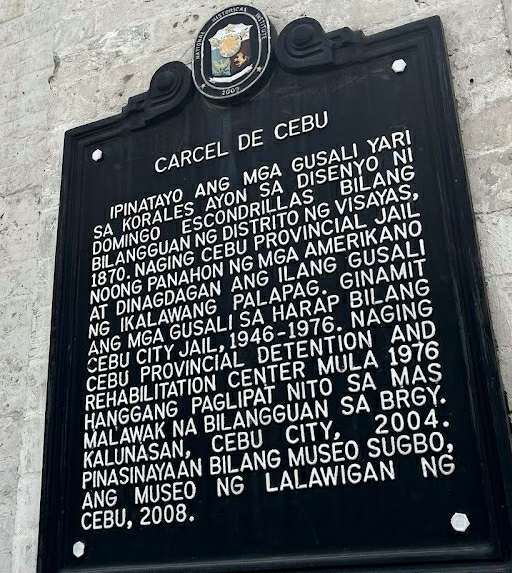

A scene at the 2010 opening of the CJJ Gallery aka Cebu Media Gallery.

Looking back, he recalled starting the museum alongside Garcia in 2008. “She was so appreciative of the museum. Now I don’t know what happened in 2023 why she had a change of heart,” said Bersales.

Museums can be profitable

While Bersales believes museums are primarily a public service, he acknowledged that in other countries, museums have successfully explored ways to become profitable. The key, he said, is to provide space for entrepreneurs and integrate commercial elements within their walls.

It’s reasonable to accept the reality: museums need to generate revenue to sustain operational costs, Bersales said.

For Museo Sugbo, among the proposals in the pipeline is to convert the lower portion of the building—previously used as an isolation cell during its time as the Cebu Provincial Detention and Rehabilitation Center (CPDRC)—into commercial space.

No enabling ordinance

Bersales and his team are lobbying for official legislative backing to institutionalize Museo Sugbo. Jobers said the museum has operated “the longest time” (more than a decade and a half) without any enabling ordinance.

CJJ Gallery, aka Cebu Media Gallery, one of more than 10 galleries at Museo Sugbo. Memo agreement ratified by the Provincial Board covers the gallery’s stay in the museum.

That may be so although for the CJJ Gallery or Cebu Media Gallery, Cebu Citizens-Press Council (CCPC) — represented by Dr. Pureza Onate and businessman Sabino Dapat, president and vice president respectively– entered into a contract with then governor Garcia, which the Provincial Board ratified on March 22, 2010. It’s not known if that legal procedure was also required for all galleries, more than 10, in the museum.

RELATED: CJJ Gallery, aka Cebu Media Gallery, under “Media Facilities, Projects Doings” category in CJJ

Steps after reopening

With Cebu Province now under a new administration and the Museo being reopened, plans are already in place to begin restoration and rehabilitation of the museum’s buildings.

The next step, he added, will be the development of a “Conservation and Management Plan.”

Bersales will work closely with Architect Robert Malayao, who will serve as the project consultant. The plan will guide the assessment of the museum’s overall condition, focusing particularly on structural integrity. “And then we will develop solutions that will guide the province on how to maintain the museum,” said Bersales. The third step will be renting out interior spaces, particularly the

former isolation cells, which will be converted into commercial spaces like cafés and boutiques. Two currently empty galleries will also be available for event bookings and gatherings.